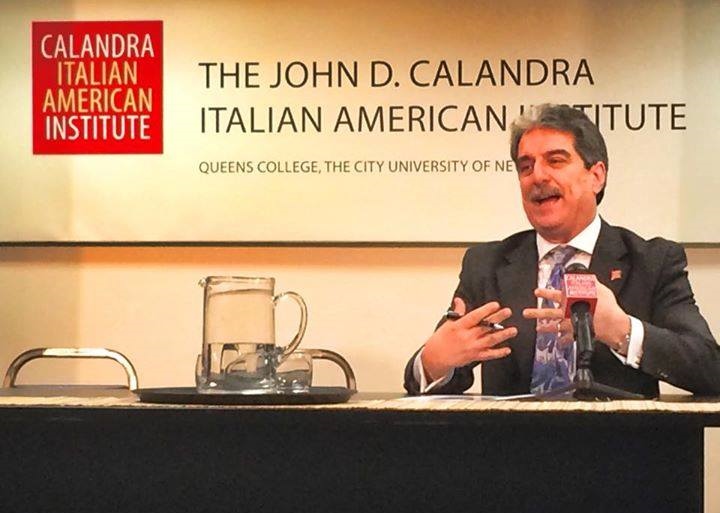

Anthony J. Tamburri (Dean of the John D. Calandra Italian American Institute)

Una vita dedicata agli Italiani in America: incontriamo Anthony J. Tamburri

There are very few people in the US and in Italy that have dedicated their life to study the Italian American community as much as Anthony Tamburri. We the Italians has been willing to interview him for a long time: and so, we're very happy to be able to offer all our readers, both in the US and in Italy, this Christmas gift. And we're grateful to Prof. Anthony J. Tamburri for this opportunity.

Anthony, you are the Dean of the John D. Calandra Italian American Institute (Queens College, CUNY) and Distinguished Professor of European Languages and Literatures. Who was John D. Calandra?

John D. Calandra was a New York state senator from the Bronx who, in the mid-1970s, began to look into complaints dating back to the late 1960s and early 1970s made by Italian Americans within The City University of New York (CUNY). Stemming from such grievances, the issues amounted to the following three: (a) faculty and staff believed that they were subject to discrimination in the workplace; (b) Italian/American students were in need of counseling services that, for them, were not available; (c) there was a large high school dropout rate that hovered around 20% through the 1980s only to drop exponentially later on to 8.6%, which was lower than the overall dropout rate of 2000.

During that period, Senator Calandra began an investigation concerned with the anti-Italian discrimination, which covered faculty and staff as well as student concerns. The various areas of concern included hiring, promotions, tenure, and appointments to major committees. Analogous realms of concern for students included support for counseling services, Italian/American clubs and centers, and Italian/American studies. At the end of his investigation, Senator Calandra released a report in January 1978 entitled "A History of Italian/American Discrimination at CUNY," in which he demonstrated that the needs and concerns of Italian/American said discrimination existed in no uncertain terms, that it was indeed a "very flagrant and obvious problem". That problem persists, for sure, to a notably significant degree today.

Which are the main activities of the Calandra Institute?

The main activities of the Calandra Institute (CI) are divided into three major areas: (a) student and counseling services; (b) outreach; (c) research.

Student and Counseling Services are offered both on-campus and at the Calandra Institute. Services include career objectives, academic counseling when appropriate, and personal counseling. In addition, our counselors visit regularly a number of high schools in areas with a high Italian/American population.

Outreach, in turn, is a much broader area to cover. It includes collaboration with other Italian/American institutions such as, for instance, the Italian Heritage and Cultural Committee of New York and the Italian American Studies Association; other institutions with which the Calandra Institute collaborates for public programming include NYU's Casa Italiana Zerillo-Marimò, the Centro Primo Levi, Columbia's Italian Academy, and the two Italian institutions, the Italian Consulate General and the Italian Cultural Institute. We have also maintained a very close relationship with the Italian American Digital Project.

Under this rubric, the Calandra Institute also publishes a monthly electronic calendar of events within the tri-state area especially. It also publishes on a regular basis as a conduit for appropriate, relevant information about the Italian/American communities, local and nation-wide, as well as announcements of the Institute's public programming. Under this rubric of outreach we can also include the numerous public activities the Calandra Institute offers. There is the regular programming of book presentations, lectures on history and culture, and film screenings of documentaries especially that chronicle the Italian/American experience. Further still, our annual conference (since 2008) and numerous symposia draw from an international population of scholars and artists who join us every spring for an examination of a specific topic: to date they have ranged from Italians in America to Children and Youth of the Italian Diaspora. In like fashion, certain members of the Calandra staff are also available to lecture on subject matter related to their professional expertise. Finally, the Calandra Institute also produces a monthly TV program, Italics, that broadcasts on CUNY TV and maintains a YouTube channel with a plethora of videos that are, in most cases, full programming we filmed both in-house and elsewhere whether it be in the greater New York area or more extensive such as Washington, DC or Elko, Nevada, for instance.

Research has developed exponentially in these past nine-plus years. In addition to the revival of the Italian American Review, we have developed two book series that publish research on social science, the arts, and the humanities. There are two basic categories of the type of research conducted within and sponsored by the Institute. One is in the area of socio-demographic research, which also includes studies of a sociological, psychological, and political science nature. The other is aesthetic, social science, and cultural studies research that often examines how Italian/American culture is articulated through an array of expressive modes such as the more traditional forms of literature, music, cinema, theater to, in turn, those more performative modes of expression such as religious festivals, socio-cultural rituals, alternative youth culture, and other aesthetic practices that may be alternative to the more traditional forms mentioned earlier (e.g., non-traditional music of Frank Zappa to hip hop, or new modes of literary expression such as the graphic novel). Finally, we have also expanded our work into the arena of teaching Italian as a second language. Through grants from Italy's Ministry of Foreign Affairs we have been able to conduct a series of international workshops and subsequently publish three books to date, including the more innovative methodology of "intercomprehension", the teaching of Italian to speakers of other Romance languages. Overall, our goal is to conduct, support, and sponsor empirical, theoretical, and analytical research that, in the end, will expand, deepen, and strengthen critical understanding of the Italian/American experience.

All three of the above-mentioned areas undergird the primary mission of the John D. Calandra Italian American Institute, which is, as was implicit in the original founding of the Italian American Institute to Foster Higher Education, to serve as an intellectual and cultural center, stimulating the study of Italian Americans through its research, scholarship, public programming and events, and counseling services, and, ultimately, bringing together a community of scholars and practitioners who can focus on and enhance the Italian/American experience both within and beyond the Italian/American community.

One of your research interests is semiotics. If I am not wrong, your opinion is that it would be more accurate, in English, to use the term "Italian American" instead of "Italo-American" and, in Italian, to use the term "Americano italiano" instead of "italo-americano". Could you please elaborate?

My concern was to bring more attention to the accuracy of naming, which, then, would bring more attention to the overall subject of Italian Americans and the study of their history and culture. My point of departure was based on a grammar rule according to the historical English primer by Strunk and White (The Elements of Style, 1919/1959), in which they point out the various uses of the hyphen, one of which is its necessity in an adjectival phrase such as "Italian/American." As a metaphor, in turn, the hyphen becomes a symbol of someone who bridges two cultures and, at the same times, lives them. In like fashion, by bringing attention to the truncated form of the first term, "Italo-" (with or without the hyphen), we could then discuss the metaphorical truncation of one's heritage culture, that the dominant culture does not grant it the value and respect one might want it to possess. As a final gesture of strident resolution, one might say, I urged the turning of the hyphen, thus transforming it into a slash (/) and, further still, bringing both cultures (Italian, American) closer together than they would be with the typical hyphen. In the end, the reader pauses to take note, and reconsiders the subject matter at hand.

In making the case in English, it appeared to me that we could do the same in Italian. The prefix "Italo-" is also used in Italian on a regular basis. Thus, here, too, in order to bring more attention to the situation of the significant lack of interest in Italian Americana on the part of the Italian collective, I thought I would use the grammatically correct couplet that also describes who we are, namely "americano italiano," the first term being the noun and the second term, the adjective of nationality, which, in Italian, follows the noun it modifies.

All of the above is reflected in curricula at the college level. The field of Italian/American studies remains an orphan child that seems not to be able to find a stable home in either American studies programs and/or departments or Italian studies programs and/or departments. It is not until such a Cinderella story finds its happy ending will we see the flourishing of other aspects of Italian American history and culture both here in the US as well as in Italy.

You also are among the founders of Bordighera Press, an independent publisher that publishes literature and poetry by and about Italian and Italian-American authors. Please tell us something more about this

Fred Gardaphé, Paolo Giordano, and I founded Bordighera Press (an imprint of Bordighera Incorporated of Lafayette, Indiana) because of the dire need at the time for a publishing outlet for Americans writers of Italian descent. Our first publication, in fact, was the journal, Voices in Italian Americana (VIA), which we launched in 1990 and continue to produce today.

First, Italian/American writers faced a series of challenges when trying to get their work published. Inevitably, they would be met with the request for something more "mafia-like" that would, in the opinion of perspective publishers at the time, better grab the reader's attention. Second, many writers who struggled to get their work in print were poets; and in 1989, when we first founded Bordighera Incorporated, poetry had lost much of its luster for trade publishers. Third, with the onset of the crisis in the publishing world here in the US in the late 1980s, it became even more difficult to have a book published.

Hence, with the initial support in the form of a grant from the Fondazione Giovanni Agnelli and our then three institutions (Purdue University, Loyola University, and Columbia College Chicago), we were able to launch and solidify a non-profit educational organization (Bordighera Incorporated) whose main activity today is the imprint Bordighera Press and occasional sponsorship of international symposia on the Italian experience in America.

You recently participated in "The Italian Diaspora Studies Summer School," a three-week summer program at the University of Calabria. In fact, you frequently work together with Italian institutions, and you often come to Italy. What can our country do to be more involved in working with the Italian American community?

The idea for the Italian Diaspora Studies Summer School (IDSSS) was born in spring 2013 during a conference in Rome, Italy. Fred Gardaphé and I planned out a weekly schedule that could be extended over a two- to four-week calendar of study. We had just launched a course on Italian/American history and culture (CLIA: Cultura e letteratura italiana americana) with the University of Calabria; it is in collaboration with professor Margherita Ganeri and her course on modern and contemporary Italian literature, for which CLIA is now an integrated part of the overall curriculum.

We decided subsequently to launch the IDSSS once we realized the great interest on the part of many graduate students and some of our colleagues. Hoping to get the minimum seven or eight participants we needed in order to make the program run, we ended up with seventeen course participants that included eight doctoral students and nine professors. They all came away with a much greater knowledge and more profound understanding of Italian/American culture in North America; subject matter included literature, history, vernacular culture, cinema, and Italian/Canadian culture as well.

We do indeed collaborate with other institutions through student exchanges, summer programs, and other research projects such as the ones with the University of Calabria. On a grand scale, specifically with regard to the educational communities from K-16, Italy has not been much involved with the history of the Italian diaspora. While the Ministry for Foreign Affairs has manifested great concern, one ministry does not suffice. More significant would be a plan to promote the study of the Italian diaspora throughout the educational system, be it at the elementary school level up and through the university, and the University of Calabria project can be an excellent model.

The Representation of Italian Americans in the Movies and on Television is one of the topics you have written about. This is an important issue that sometimes divides the Italian American community. What's your idea about it?

The topic can indeed be divisive. It is true that the representation of Italians in the States has not always been positive; this is especially true for the beginning of the twentieth century. It is also true that there is a certain component of Italian Americans who abhor any non-positive representation and complain vociferously about it. And while this may have its impact, it is also true that we need to try to understand better the reasons for such representation. In so doing, we can also discover the history of reception of Italians in the United States and thus better comprehend the reasons for such. My inclination is that we should complain less and study more the ragion d'essere of such negative representation.

Yet, there is another aspect to this, and it involves education. We need to engage in a concerted effort on a national level that involves having Italian/American studies courses become part of the university curriculum. But it is a challenge to be sure. The easiest way for such a campaign to be effective is to work within in three different areas and/or departments: history, sociology, and, more important, Italian departments. However, what has become apparent is that while many Italian studies departments nationally are supportive of such a curriculum — Queens College, for example, has a bouquet of four graduate courses, the only within CUNY — there are other Italian studies programs around the country that are not. In some ways, this is a residue of the likes of Antonio Rugiero, Emilio Cecchi, Mario Soldati, Giuseppe Prezzolini, and the like; those Italians who, during the first half of the twentieth century, either visited the United States or lived here for an extensive period, and wrote most critically, and I would add cynically, about the Italian immigrants and their children they found here. This has contributed significantly, to be sure, to a negative opinion of the Italian in America, especially of that era.

One of the reasons we have engaged in more collaboration with Italian universities and why we have developed the IDSSS is precisely for this reason. We need to be sure that those in Italy have a greater and more profound knowledge of who we are and what we do. This is also one of the reasons we received a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to conduct a week-long workshop at the Rockefeller Foundation's Center in Bellagio, Italy. Nonetheless, I contend that the education is for both the greater Italian and non-Italian community in the States as well as the greater collective consciousness of Italy.

You are also the executive producer of the TV program Italics and a member of the founding directors of the Internet portal i-Italy.org: two successful projects that help the American people in knowing more about both Italian Americans and Italy in the US Can you please describe them? What's in the future of these two admirable projects?

Italics has been around for almost thirty years. It is a monthly program on CUNY TV and is funded both through the Calandra Institute's state allotment as well as monies from CUNY central offices. The quality of programming has become increasingly more diverse in subject matter. Both through the Calandra Institute's programming and Italics, we have decided in these past five years especially to tackle a few hot-button issues that some self-proclaimed leaders in the Italian/American community have seemingly shunned. Guido culture was one of these pesky topics that caused an uproar from certain corners of the community, refusing, as they did, to engage in any sort of dialogue and/or debate, and instead, waging a battle of sorts that in the end had no impact any significance or import. Through Italics we also visited the more sensitive and humane issues surrounding the LGBTQ communities within Italian America, one show on gay men, the other on LGBT. These two shows were among the top-rated on CUNY TV's website for the weeks in which they aired. In its continued quest for innovative programming, Italics visited the 29th Annual National Cowboy Poetry Gathering in 2013, which featured Italian butteri and local Italian American ranchers as well as the award-winning Italian American cowboy poet, Paul Zarzyski. It airs once a month on CUNY TV's cable channel, which time constraints unfortunately limits us in what we can share with our greater New York audience.

My involvement with i-Italy.org (IADP: Italian American Digital Project) stems from a year-long program of study (EUSIC: Empowerment of US-Italy Community) in new media journalism that Letizia Airos and Ottorino Cappelli coordinated back in 2006-2007 with a generous grant. The Calandra Institute was directly involved in the cultural realm of EUSIC, offering lessons on Italian/American culture and history to the group of students. Once the course ended, both Airos and Cappelli founded the web-site www.i-Italy.org, and numerous of the EUSIC students collaborated at the beginning. IADP, in the meantime, needed a place to call home, and at that time we had available space to offer to them. They have indeed been with us since 2008. Over these past seven years IADP has expanded greatly from a website only to both a bi-monthly magazine and a weekly TV program that highlight all things Italian within the greater New York metropolitan area and, when appropriate, addresses some of the major issues that might impact Italians in America.

What ultimately needs to be said with regard to both TV programs is that they are the only two truly professionally produced programs dedicated to the reporting and, hence, promotion of all things Italian/American and Italian, be those things the more obvious to the less recognized. What they cover at this juncture, especially given their respectively limited resources, is admirable to say the least. That said, your question then also begs yet another: What support do these programs receive from the community? The answer to that is long and complex, and, for now, let me just say that any assistance would be most welcomed.

What's your opinion about the recent events against Christopher Columbus and the Columbus Day?

I believe that this is one of those very hot-button issues that have been a long time coming. Back in 1992 Columbus and his voyages had been historically revisited and mightily scrutinized. Any attempts by certain members of the Italian/American community to save the name "Christopher Columbus Day" should have been initiated back then. But for all practical purposes, nothing of any major significance had come to pass, as far as I can remember. For instance, I know of no attempts on the part of the Italian/American community to dialogue with leaders of the Native-American community. It seems to me that such conversations were necessary twenty-plus years ago, as they remain so today.

Given the recent discussion sponsored by the Italian American Leadership Council of the National Italian American Foundation at its 2015 Gala, we find ourselves now in a situation in which it is no longer clear what the struggle is. Do people want to save the name Columbus Day? Or, do people want to be sure that if the name of the day were changed, that it nevertheless would be a day in recognition of Italian/American culture and history? As I mentioned above, knowledge and learning about Italian/American history is critical, as several scholars have unpacked the complicated ways in which Italian Americans became associated with the historical personage.

As we know, October 12 celebrates Christopher Columbus as the recognized discoverer of the Americas; and lumped into this is the celebration of Italian/American culture and history. This, to be sure, is the crux of the matter. Must we tie them both together ineradicably, regardless of what we have learned in the past thirty-plus years about Columbus's voyages, so that the one cannot be separated from the other? In so doing, what do we then say to our younger Italian/American brothers and sisters of the newer generations, many of whom prefer to promote Italian/American heritage and culture and not necessarily what they see as the troublesome symbol in the name Columbus Day? The unscientific survey in Italics's video reportage of the NIAF discussion begs such a question. Namely, do Columbus and all that he/it as symbol represent constitute what we want to celebrate as Italian/American culture and history? For some, yes; for others, no; and the divide is surely one of a generational character. But what we do know is that adjectives and predicate nouns such as "misguided," "childish," and "crackpot" with regard to those who question Columbus are not going to assist in the resolution of any internal issues, for sure.

What is needed to quell this internal dispute—as well as others that have come to the fore in the past—is a much more profound and well-informed discussion on the issue, one that may very well be based in dialogue and debate, but not denigration and dismissal, as some have done in the past other issues. That said, in this regard, I would suggest that the place to begin is for people to view the 30-minute documentary Columbus Day Legacy (2011; Bennie Klain, director).

You may be interested

-

'Phantom Limb': A Conversation With Dennis...

Dennis Palumbo is a thriller writer and psychotherapist in private practice. He's the auth...

-

2015 scholarship competition

The La Famiglia Scholarship committee is pleased to announce the financial aid competition...

-

A wreath for Columbus and three crowns for t...

The Columbus Day Committee of Atlantic City along with the Bonnie Blue Foundation annually...

-

An Unlikely Union: The love-hate story of Ne...

Award-winning author and Brooklynite Paul Moses is back with a historic yet dazzling sto...

-

Cathedral of St. John the Divine, Oratorio S...

For the first time ever, The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, in collaboration with the O...

-

Davide Gambino è il miglior "Young Italian F...

Si intitola Pietra Pesante, ed è il miglior giovane documentario italiano, a detta della N...

-

Emanuele: cervello d'Italia al Mit di Boston

Si chiama Emanuele Ceccarelli lo studente del liceo Galvani di Bologna unico italiano amme...

-

Former Montclair resident turns recipes into...

Former Montclair resident Linda Carman watched her father's dream roll off the presses thi...