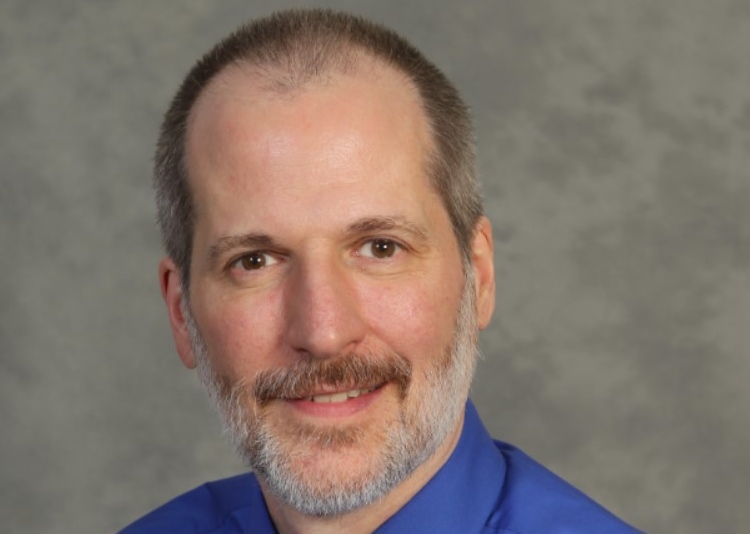

Paul Basile (Co-founder of the Italian American War Veterans Museum)

Celebrando la memoria degli Italoamericani che hanno combattuto per l'America

Among the many fields that have seen the Italians emigrated in America and their following generations show talent, determination and success in their new country, the defense of the United States is particularly important. Italy has provided several heroes to the US Army, the Marines and the other branches of the United States Armed Forces.

In Chicago there is a museum which pays the due respect to the Italian American War Veterans. I exist because my father was saved by the fifth army – and among them, by the Italian Americans who chose America and then enlisted and asked to be sent to Europe to free their old country - during the second world war. So as these days America celebrates the Memorial Day, commemorating all men and women who have died in military service for the United States, it is for me a honor and a privilege to be able to talk to Paul Basile, one of those who made possible this place: my eternal gratitude goes to those heroes without whom I wouldn't even be here.

Paul, we think that the idea of a museum that allows us to remember, tell and pay respect to the stories of the Italian who served in the defense of the United States from the Revolutionary War to the present is very commendable, and we sincerely admire both the realization of that idea, and those who had the idea come through. Please tell us more about how and when the museum was created, and describe it for our readers

The Italian American Veterans Museum and Library is the brainchild of Anthony Fornelli, a longtime national and local community leader. His uncle, Orlando "Lon" Fornelli was quite the hero in World War II. His unit was hemmed in by sniper fire on Guadalcanal and he went out into the jungle by himself, shot 13 snipers out of the trees, and liberated his unit.

Tony spent several years trying to convince various organizations in the community to create a museum in honor of the millions of Italian Americans like his uncle who fought so bravely in the service of their country. When his uncle passed away, Tony took matters into his own hands, using his own resources to create the museum and assembling a team of community activists to move the museum forward. We open our doors on Memorial Day 2006.

What's the story of the contributions of the Italian Americans throughout the different wars?

Over the centuries, Italian Americans have signed the Declaration of Independence, inspired the phrase "All men are created equal", turned the tide in the war against the Barbary pirates of Tripoli; made up the largest ethnic fighting force in World War II; earned more than two dozen Congressional Medals of Honor; held the top three spots on the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

This is only the tip of the iceberg, as they say. To find out more about the museum, you can click on the following link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8QNcogI-0w8&feature=em-upload_owner-smbtn

Who are the most important Italian heroes commemorated in the museum?

We commemorate several legendary Americans of Italian descent, including William Paca, who signed the Declaration of Independence; World War II flying ace Dominic Gentile; and John Basilone, the most decorated and admired enlisted man in American military history.

But the museum is more focused on the unsung heroes: the men and women who served anonymously in the defense of their country. We feel that they are all important heroes, and it's our mission to tell their stories, and to filter the larger movements in military history through their hearts, minds and experiences.

Here are some of their stories, direct from the museum's exhibits:

High Noon

It was like a scene from a Gary Cooper Western. John Del Medico and one other Army MP moved cautiously into a French town that had been captured from the Nazis but which wasn't yet flying the white flag. Suddenly, three German soldiers ran across the street toward a house and Del Medico and his partner shot at them. Del Medico grabbed one, held a gun to his head and, through him, convinced his entire troop to surrender. Civilians of the village watched as white flags appeared and the German soldiers came out of the building, one by one, and threw their firearms in a pile on the ground. All told, Del Medico and his partner captured 126 Nazis that day, and freed 800 Russian POWs.

Angel in the Air

"I pray that some day in the future I may read these words I have written in the peace and comfort of our home, all safe and sound," wrote Vincent Allegrini in the final entry of his diary before shipping out. The Army Air Corps lieutenant not only made it home, he made sure hundreds of other soldiers did as well. During the battle for Moratai, his division was pinned down in the jungle and running quickly out of food. Risking life and limb, Allegrini dodged enemy fire while flying low over mountainous terrain to air drop supplies to his division. Ninety-five percent of the supplies reached their destination. He repeated the feat on land during the crucial Philippines campaign.

To Hell and Back

When Mario "Motts" Tonelli entered the Armed Forces in World War II, he was a strapping young fullback for the Chicago Cardinals, having just completed an All-American career with the Fighting Irish of Notre Dame. Four years later, when he returned from what was supposed to be a one-year tour of duty, he was emaciated beyond recognition, having survived one of the worst atrocities ever visited upon American troops. Tonelli and 23,000 other starving and fever-ridden soldiers were forced to slog 70 miles through dense jungle and stifling heat by Japanese captors who killed any prisoner who lagged behind or paused to help a fallen comrade. By the time the infamous Bataan Death March was over, 14,000 Americans were dead, and the remaining 9,000 were subjected to inhuman conditions and inconceivable brutality until the end of the war. Tonelli survived the ordeal thanks to a combination of physical and mental toughness that was rooted in his Italian upbringing. "I used to hear dago, wop, greaseball all the time, but my father told me to never mind it, " he recalled. "Maybe that helped when the guards insulted us virtually every minute. I remembered my father always telling me that we had to do better because we were Italian."

You are also were also one of the driving forces behind the documentary "5,000 Miles From Home". What is it about?

"5,000 Miles From Home" tracks the impact of World War II on the Chicago-area Italian American community. Faced with the grim fact that World War II veterans were dying at the rate of 2,000 per day, Tony Fornelli felt that it was incumbent upon us to tell their stories while they were still alive to share them with us. The documentary was directed and produced by Jim Distasio and Mark McCutcheon. We asked the same exhaustive list of questions to 25 Italian American World War II veterans and their family members. The answers we came up with were as remarkable in their uniformity as they were fascinating in their diversity.

To a man, these veterans were children of Italian immigrants who didn't speak English until they went to kindergarten, grew up thinking of themselves as much as Italians as Americans, and became truly American in the crucible of military conflict. The war dragged them from the comfort of their ethnic enclaves, showed them the world, and gave them the wherewithal when they returned to leave their ethnic past behind as they pursued the American Dream.

Our documentary won six national Telly awards and two local Emmys. A documentary of that caliber would cost between $200,000 and $300,000 to create, but we were able to produce within the confines of a $22,000 grant bestowed upon us by UNICO National. To find out more, click in the following link: www.5000milesfromhome.com

Another important role you have in Italian American community is being the editor of the monthly magazine "Fra Noi": tell us something about it.

I've been the editor of Fra Noi since 1990. A lot changed when I took over, and a lot has changed since. Fra Noi was launched in April 1960 as a fundraising vehicle for Villa Scalabrini, a nursing home founded 10 years earlier by the Scalabrini Fathers specifically to meet the needs of the Italian American community.

It started out as a four-page 8.5 x 11 newsletter but quickly morphed into a 24-page tabloid newspaper, filled with news that bore a distinctive slant. Back then, Fra Noi's editorial policy was simple: you gave a lot of money to the Villa, you got a lot of coverage in Fra Noi; you gave a little money to the Villa, you got a little coverage in Fra Noi; you gave no money to the Villa, it's as if you didn't exist. It was basically a newsletter in newspaper's clothing.

The fathers sold as many ads and subscriptions as they could, mailed the newspaper for free to thousands of households, and operated at a significant loss that was easily justified by the generosity that Fra Noi inspired in the community.

When an archdiocesan social service agency took control of Villa Scalabrini in the mid-1980s, the Villa was a mature institution that didn't require the same level of mass marketing. When they looked at Fra Noi, all they saw was a publication that was bleeding money and subscribers at an alarming rate.

The two years before I was hired, the newspaper had lost $200,000 and 2,000 of its 7,000 subscribers, mainly because the business was poorly run and the articles were poorly written, but also because the community had outgrown the Villa and the Villa was trying to sell them someone else's newsletter.

I was hired in 1990 to reverse those trends, which I did by dramatically cutting costs and improving the quality of the writing while expanding the focus to appeal to as broad a readership as our budget would allow. Luckily for the community, it took me longer to get to break-even than Catholic Charities had the patience for.

In 1995, five community leaders — Anthony Fornelli, Anthony Spina, Amy Mazzolin, Renato Turano, and Paul Butera — stepped in and saved Fra Noi, pouring personal funds into the fledgling enterprise to cover a sizeable accumulated debt. (It's important to note that the board members of Fra Noi have never profited from their role as board members, nor will they ever. They genuinely view themselves as keepers of a flame that must never be extinguished.)

Fra Noi broke even two years later, and all of the shareholder money used to cover the initial debt is back in the bank as a cash flow buffer. We've been doing well on the circulation front, too, slowing rebuilding the readership to about 6,300.

There are a couple of reasons for this dramatic turnaround. First, there are the advertisers, who view their financial commitment to Fra Noi not just as a business investment, but as an investment in their heritage. Equally important are the enormously dedicated and talented individuals who make up the Fra Noi family of staff members and correspondents.

We never have had enough money to promote the publication, but it has enjoyed incremental growth none-the-less because the product is so good, it sells itself. Through a diversity of well-written articles that cover the local, national and international fronts, Fra Noi offers the community not only a mirror in which it can see itself, but also a window through which it can see the larger world.

Fra Noi went through several incarnations as a newspaper before we transformed it into a magazine in April 2011. We launched a hybrid local/national website around the same time (www.franoi.com) and a regional magazine and website for the Boston-area Italian American community in January 2013. (www.bostoniano.info)

You may be interested

-

“The Hill” St. Louis’ Little Italy

When the fire hydrants begin to look like Italian flags with green, red and white stripes,...

-

An Unlikely Union: The love-hate story of Ne...

Award-winning author and Brooklynite Paul Moses is back with a historic yet dazzling sto...

-

Davide Gambino è il miglior "Young Italian F...

Si intitola Pietra Pesante, ed è il miglior giovane documentario italiano, a detta della N...

-

Jean Lenti Ponsetto Honored as National Ital...

The National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame is proud to announce its inductees and h...

-

Polisena delivers address as state lawmakers...

"Italian-Americans came to our country, and state, poor and proud," Johnston Mayor Joseph...

-

The “Little Italies” of Michigan

In doing reseach for this post, I was sure that Italian immigrants found their way to Detr...

-

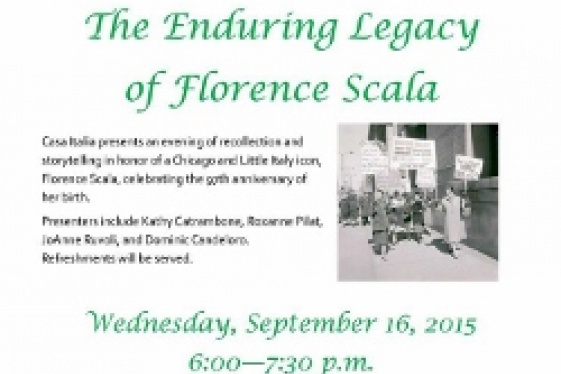

The Enduring Legacy of Florence Scala

Wednesday September 16 - 6 /7,30 PM - Roosevelt Branch Library - 1101 W Taylor S...

-

Ybor City – Florida’s Little Italy

"The people who had lived for centuries in Sicilian villages perched on hilltops for prote...