BY: Marco Mostarda for NavLab

The destruction of the statues of Columbus is certainly no surprise, because for some time now in the USA Columbus has become a symbol of the beginning of the process of extermination of Native Americans. It is not just a logical fallacy of the "post hoc, ergo propter hoc" kind, so the discoverer of the Americas is ipso facto responsible for everything that the conquest has brought with it.

Much more specific facts are attributed to Columbus, such as the beginning of the exploitation and the massacres against the Taíno that marked the foundation of the colony of Hispaniola; even if, on closer inspection, this should be due more to Columbus' shortcomings as administrator and his absenteeism - to the extent that he wanted to exercise the office of governor of the new territories discovered while following his exploration trips - than to a seriously meditated exploitation project.

Then, of course, Columbus was a man of his time: someone who wanted to extract a profit from all that enterprise also through the exploitation of the human capital of the discovered territories. In the face of this there are, if anything, precise elements to sustain that Columbus was somewhat better, in his feelings towards the natives, than his contemporaries: this is demonstrated by the "Memorial a los Reyes Catolicos" of 1501, in which he argues the need to send qualified personnel to administer justice among both the Spanish and the Indians, observing "que son tratados ansí los unos como los otros más siguendo la crueldad que la razón" (that treat each other more with cruelty than with reason).

Where, therefore, does the dark legend about Columbus come from, which increasingly emerges in the contemporary world, especially coinciding with protest movements like the one we are witnessing? Essentially from the Bobadilla dossier that would have led to his imprisonment and his removal as governor; but in this regard it will be appropriate to take a step back first.

With the so-called Capitulations of Santa Fé of April 17, 1492, Columbus had snatched from the Crown some very good concessions, to say the least, on what should have been his prerogatives on the newly discovered lands during his voyages. In short, we could summarize them in concession of the title (transmissible by inheritance) of Admiral of the Ocean Sea, exercise of the governorship on all the discovered lands, a tenth for himself of all the riches extracted from the colonies. If Columbus had discovered an archipelago such as the Azores, it would have ended there and no one would have deigned to question these rights that the Capitulations solemnly recognized to him. But since the lands discovered by Columbus were immense, and the riches of those lands promised to be proportionately great, the problem arose that those Capitulations gave a single man too much power and too much wealth.

Two factors made the picture worse. First, like any businessman in a foreign land, Columbus tended to distribute offices and positions of responsibility among his friends and family, first of all his younger brother Bartolomeo. Ferdinand Magellan would have behaved in the same way when preparing his circumnavigation expedition (involving, for example, his brother-in-law Duarte Barbosa, who would become captain of Victoria after the mutiny in Puerto San Julian). This inclination to maintain the management of business within a small circle, when assigning the posts in the new colony of Hispaniola, was not liked at all by the Spanish, generating in them the conviction that they had been cut off - and by a foreigner - from the exploitation of the resources of "their" colonies.

Moreover, Columbus proved to be an undemocratic governor - even if, in hindsight, his decision to centralize and ration all available food resources was probably the right one, since the settlers of Hispaniola began to starve to death when they contravened his orders. Yes, like any man of the late 15th century, the exercise of violence and strict respect for the hierarchy were for Columbus essential conditions in the exercise of social relations: no, Columbus was no more violent than the average of the period and the man himself was not particularly brutal. His desire for evangelization of the natives was intimately felt, for example, coming from a deeply religious man who loved to sign at the bottom of his letters like Christus ferens (bearer of Christ). And I have already pointed out that, in the memorial of 1501, he fought for a fairer and more rational administration of justice in the new colony, both for the Spanish and for the natives (an order of problems that would never have touched a man like Pizarro, for example).

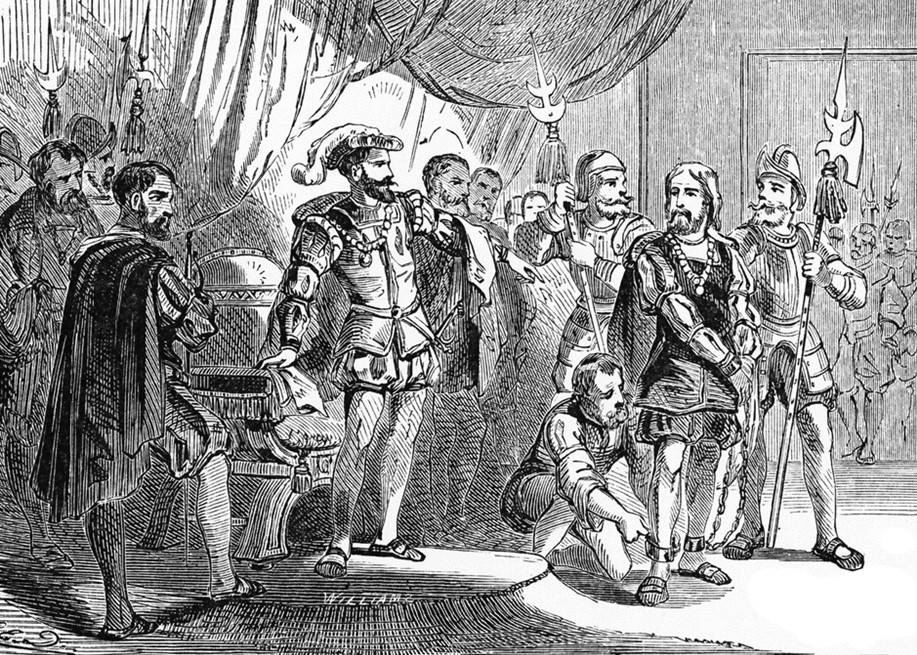

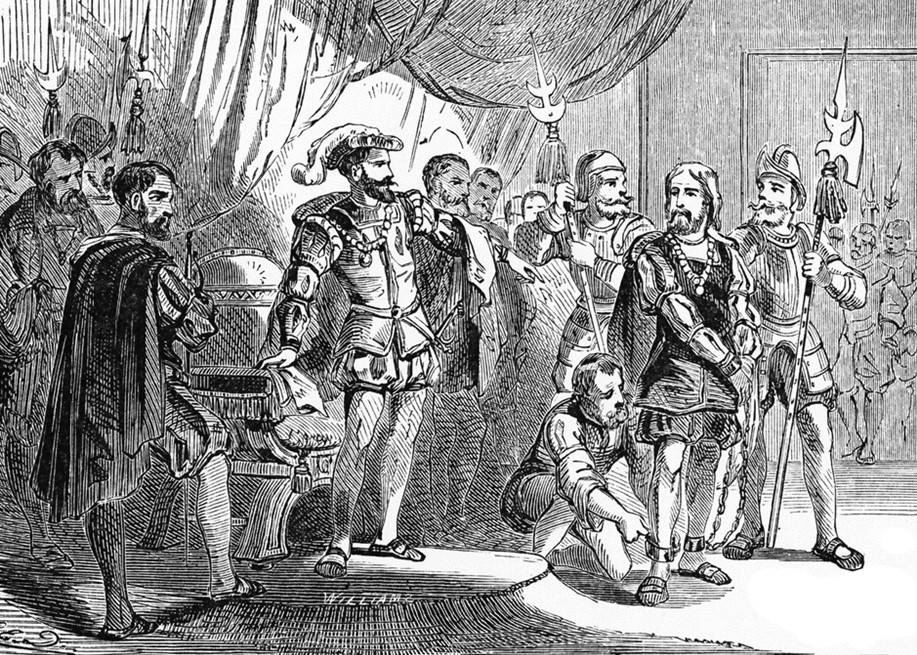

The settlers' discontent soon degenerated into unrest in the new colony, with the clergy blowing on the fire of the revolt for intolerance of the condition of subordination to the authority of the governor decided by the Capitulations of Santa Fé. In reaction the Crown sent a juez pesquisidor (an investigating prosecutor), Francisco de Bobadilla, to Hispaniola to examine the situation and judge on the merits of the accusations made against Columbus. The balance of power between the governor and the prosecutor were not at all well delineated, and it is not clear whether Bobadilla, when arresting Columbus (who had refused to recognize the authority of the former) committed an arbitrary act or was within the powers connected with his office. The fact is that Bobadilla collected a considerable accusatory dossier on Columbus, collecting all the complaints and rumors that could be gathered among the colonists: and since they were people who had specific reasons of resentment towards the Genoese, and in some cases excellent prospects of obtaining something from his removal, such accusations certainly cannot be considered super partes. They range from specific accusations of brutal punishments inflicted by Columbus against Spaniards of free will in order to maintain order, to less credible accusations of cruelty committed on a large scale by the hated Genoese clan and to incredible and fanciful voices tout court, such as the one that wanted Columbus to betray the Spaniards and hand over the new colonies to no less than the Republic of Genoa. For this reason I have underlined how the Bobadilla dossier should be evaluated with great caution because it is a very partial source, much more than the general partiality that afflicts any historical source. It should also be remembered that Columbus, once back in Spain, obtained the dismissal of the accusations contained in the dossier collected by the prosecutor and the exoneration of Bobadilla himself from the office; but the prerogatives that the Capitulations recognized him fell together with the accusations. This is a good clue to the instrumental nature of the latter, which, on closer inspection, had achieved its goal: to strip Columbus of the rights enshrined in his contract with the Crown.

You may be interested

-

'Atmosphere of anger' in Glen Rock and beyond...

The debate over turning Columbus Day into Indigenous Peoples’ Day has people riled up on b...

-

'Columbus' ship Pinta docks in Fort Walton Be...

A little bit of living history will be on display in Fort Walton Beach now through Jan. 2....

-

'Don't Honor Genocide' Graffiti Painted on Co...

The statue of explorer Christopher Columbus that looms over Astoria Boulevard was vandaliz...

-

'Exactly what we were trying to avoid': Chris...

Red paint was splattered across the Christopher Columbus statue in San Antonio's Columbus...

-

'It is time to return them': Italian-American...

The Joint Civic Committee of Italian Americans (JCCIA) said Mayor Lightfoot and the City o...

-

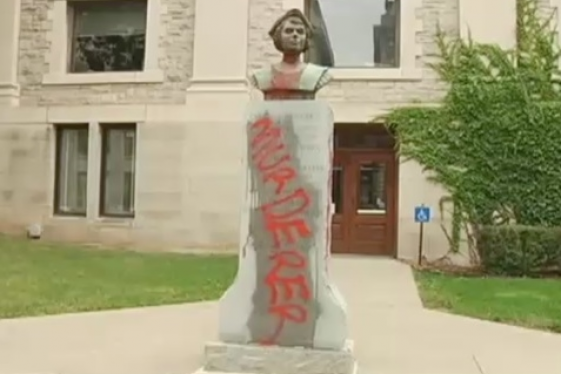

'Murderer': Another Upstate NY Christopher Co...

With just a month left before Columbus Day, another prominent statue of Christopher Columb...

-

‘Basta!’: Italian-Americans Fume As Boston Ma...

Boston’s Acting Mayor Kim Janey sparked howls of anger when she unilaterally whacked Colum...

-

‘F—k Columbus’ graffiti found on Manhattan st...

Vandals scrawled, “F–k Columbus” on the base of the monument of the explorer in Columbus C...