Maria Cristina Loi (Curator of the exhibition "Thomas Jefferson - An Italian President")

Thomas Jefferson: fu un "Presidente italiano"?

One of the issues that often arise in the Italian American community is whether there will ever be an Italian President. For this reason, but not just for this, it is of great interest that Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò has presented an exhibition titled "Thomas Jefferson - An Italian President" in New York last spring.

Today we talk to the curator of this project, Professor Maria Cristina Loi, who tells us the important and unique relationship between Thomas Jefferson and our country

Professor Loi, last April Casa Zerilli-Marimò NYU hosted the multimedia exhibition "Thomas Jefferson - An Italian President", of which you are the curator. Can you please describe it?

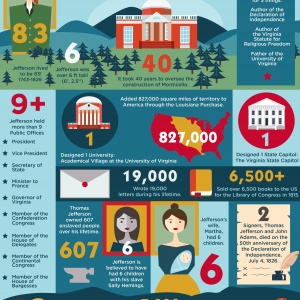

This project was born with the intention of telling a particular aspect of the intense activity of Thomas Jefferson, third US President, lawyer, architect, lawyer, botanist scholar, book collector: the influence that the Italian culture has had in its work, which gave birth to his great love for Italy that has poured into many fields of a multiform activity. Especially - but not only - as a promoter of a new architecture for his young nation.

I started dealing with Thomas Jefferson in the 1980s, during my degree in the faculty of architecture in Rome, where I studied his architectural work and since then I have been continuously involved in this theme, however inseparable from Jefferson as a politician and man of law: he was a multi-faceted man, and his interests intersected, influencing one another.

The project was born from an exchange of ideas and meetings with Stefano Albertini, Director of Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò of New York University, and a lecturer at the Department of Italian Studies at the same university. From these discussions emerged the desire to create an exhibition that would testify to the strong link between the architect-President and our country, a theme perfectly in line with the initiatives and research carried out by the Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò, wonderful and very active Center of Italian culture in the heart of the Village. I am very grateful to Stefano Albertini for having wanted to promote this initiative, and I would like to take this opportunity to thank him and all the staff of Casa Italiana. The title of the exhibition originated from one of his ideas, it seemed very effective to emphasize how Italian is Jefferson's long and intense activity. And it is a peculiar aspect, if we consider that he only visited Italy for about twenty days.

This is a small exhibition, organized in three main parts. It opens with a video that has the intent to synthesize with a sequence of images the different aspects of Italy that have influenced Jefferson: nature, landscapes, architecture, the latter viewed from real life but also and especially studied through the many books bought by Jefferson during his existence. In a second part, Jefferson's trip to Italy is told through the pictures of the places he visited, with some quotes from the pages of his Travel Diary. The protagonists of the third part are the books, the primary source of knowledge of ancient architecture, which Jefferson relied on to inspire the architecture of the young nation. His latest project, the one for the University of Virginia, is illustrated as a sum of synthesis of his ideals.

What were the most inspirational Italian place sites for Jefferson?

Jefferson was Minister Plenipotentiary in Paris for 5 years, from 1784 to 1789. During these years he organized a series of trips, where he learned about places and people, new cities and important political figures, and acquired a large number of books.

He came in Italy in 1787 and stayed just twenty days. This has always been considered very peculiar, because, as an architect, Thomas Jefferson will always be connected with the figure of Andrea Palladio, the great Italian architect whose works could be reached during his trip to Italy in just a day and a half, perhaps two, on horseback.

Jefferson arrives in Italy in spring, in April 1787, coming from the south of France, passing by Ventimiglia. The pattern of his journey is like a ring that includes three major cities, Turin, Genoa and Milan, which in those years were undergoing profound transformations: for example, let's think about the Neoclassical Milan by Giuseppe Piermarini, or the realization of Teatro La Scala. Besides, these are are also very important years for the transformation of the habitat in search of a new relationship between city and country: an aspect that will then be interpreted by Jefferson in an American key, because the vast expanses and the rich and uncontaminated nature constituted the premises for a development which was expected - and hoped - to be profoundly different from the examples of the old continent.

There are many inspirations that Jefferson could draw from his brief stay in Italy. Being such a short travel - both due to his political commitments and the impending arrival of his daughter in Paris - there was little talk about Jefferson's architect on this trip. However, his Travel Diary gives a very interesting documentation about architecture, to be studied together with the correspondence of the same period.

However, the interest in agricultural production was more explicit. In his notes, Jefferson focuses on the study of rice fields: he wants to test the variety of Italian rice to compare with that produced in the southern US states. This interest also concerns a whole range of products, plants and animals, to understand if, how and at what price they can be imported in America, possibly exchanging them with typically American products such as Virginia tobacco. One of Jefferson's greatest interests is the vineyards, in order to understand what can be imported in the Virginia climate: the history of wine production is also linked to the name of Filippo Mazzei, and to date Virginia still produces Jefferson's wine. In addition, Jefferson visits and finds some interesting Parmesan production centers in Rozzano, near Milan.

Jefferson was a very curious and educated man, who made contact with Italian aristocrats, politicians and intellectuals, and tried to study how to improve trade and how to transfer some of the best Italian products to America. An Italian scholar (Marco Sioli, 1997) has acutely noted that his trip to Italy can be considered a sort of anticipation of what would then be the exploration towards the Pacific.

Yet, it seems that the theme of Palladio's architecture is one of the most important, in the relationship between Jefferson and Italy ...

It's true. Despite the pragmatic nature of his journey and the interest in the production and cultivation of our territory, studies confirm this interest for Italian architecture and for Andrea Palladio's work. In my current research, I am deepening these aspects of the trip to Italy, for example what happened on the two days in Milan, what were the architectures visited and with which artists he came into contact. Or what could have been the impact of a city like Turin over the creation of a new image of American brick architecture; or, moreover, the influence exerted by Genoese villas open to the landscape.

We could think of a double face of Thomas Jefferson's Italy. On the one hand, a "Color Italy", the one of the vineyards, the great landscapes, even if not in a very mild climate, because in the Travel Diary he even talks of a few days of snow on the Appennines. On the other hand, an "Italy in black and white", which is the one he does not see directly, but he gets to know through his many books. Jefferson bought many books, especially in England. During his years in Europe, a lot of works about architecture and art are published, the result of recent archaeological campaigns, the new rediscovery of the Ancient, now not only identified with Rome but also with Greece, Egypt, The East. Jefferson's rich library is the most explicit testimony to these interests.

Well: in this period spent in Italy, Jefferson, always defined by historiography as a "Palladian", did not go to see in person the works of the great architect. Probably, as mentioned above, partly because of logistic difficulties, but partly because, probably, he thought sufficient to have knowledge of these works through the books. It's a paradox, because we're talking about a man who will define the Palladian Treaty as his Bible. Even more surprising, if we consider that he used the English editions of Giacomo Leoni as a main reference, which differed very much from the original Venetian version from 1570. Jefferson's "Palladianesism" has always been widely debated, already from the studies on Andrea Palladio of the American scholar James Ackerman, and remains an open issue today.

Jefferson is then deeply inspired by Italian architecture, and by Palladio in particular, but he knows it almost exclusively through two-dimensional images, which does not allow a perfect perception of three-dimensional architectural space. We can therefore say that Jefferson's "Palladianesism" is actually very atypical, an apparent one, for buildings whose interior will be modified and adapted to the specific needs of the young American nation. The need to be inspired by the Italian master was very important because in Virginia Jefferson had found an architectural style that he deemed totally unsatisfactory. He argued that the Genius of Architecture had thrown himself at his Earth, and there was, of course, a political critique against the British. An important scholar, Frederick Nichols, wrote that Jefferson wanted to write a Declaration of Independence also of American architecture, to create a new image independent and free from English.

Is the exhibition available to be shown in other cities in the United States?

The exhibition was at Casa Italiana between March and April 2017, and the will with Stefano Albertini is to propose it and circulate it in the United States, at the Italian culture centers and more generally at universities and other cultural institutions, the first being the University of Virginia, certainly the one most representing of Jefferson's legacy. The "Rotunda", the university library - now home to offices - is an exemplary building: to house the "temple of knowledge" Jefferson chose to model the Pantheon, one of the more solemn models of ancient Rome's architecture.

You have a Master of Arts degree from Columbia University's Art History and Archeology Department. Widening the look beyond Palladio, Italian architecture has always been an exceptional source of inspiration for the United States, right?

The examples are so many. The first things to remember are, for example, the major stations in New York, the Penn Station and the Grand Central, inspired by the great thermal spas of imperial Rome, with the majestic central hall and a dense network of distribution elements and spaces encircled all around.

And then there's Washington, the city of power, which for its most representative monuments has modeled temples, obelisks, sculptural groups: examples of antiquity, solemn and timeless models. Among them we can find the Pantheon, chosen by John Russell Pope for Jefferson Memorial.

But besides, let's think about the influence of Italian architecture and design in the last century: from Zanuso to Gardella to Caccia Dominioni, to name just a few examples, these great masters moved on various levels: from the creation of design objects to the realization of real buildings, schools, homes, exhibition spaces, up to designing entire neighborhoods and parts of the city, according to the famous "From the spoon to the city" motto. These experiences have been extremely influential in America.

But these are just a few examples. We can say, more generally, that Italian culture, in many fields, has always had a strong influence in America, one that has developed in a relationship of mutual exchange of ideas, artists and skills, and this has had an important reflection also in university programs. When I was studying at Columbia University, the Department of Art History and Archeology program covered a long series of courses on Italian architecture: ancient Rome, the Renaissance, the Baroque, the eighteenth century, taught by the best scholars in the world on these topics.

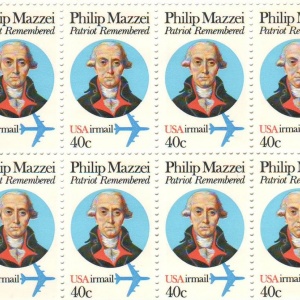

Thomas Jefferson was the main contributor of the United States Declaration of Independence in July 1776: one of the most important and famous phrases in it is "All men are created equal." It was the Italian Filippo Mazzei to inspire Jefferson for this phrase: what was the relationship between the two?

This is a very interesting topic, which has been very popular in recent years. Mazzei was a very important figure: an eclectic man whose interests ranged from economics to politics, one of the greatest experts on the American situation. He had met with all of the first US Presidents and probably, among them, his most important and solid relationship was that with Jefferson. There are several topics that Mazzei, who had an estate near Monticello, was interested in and discussed with Jefferson: from economics to politics, from religious freedom to the import from Italy of animals and products unknown in America.

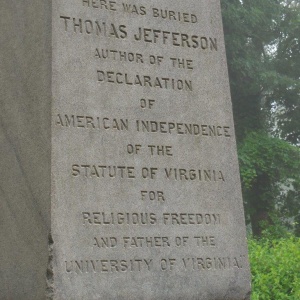

There is, then, the crucial question of the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson's life is effectively summed up in the sentence that he himself wanted to be carved in his tombstone: "Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of American Independence, of the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom and Father of the University of Virginia." It is always said that in the Declaration of Independence, based on principles of equality and freedom, Jefferson draws much from Mazzei's thought, from his idea that all men are created equal, and that all men have the inalienable right to happiness.

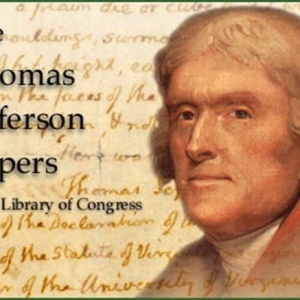

We have a rich and accurate documentation from Jefferson, nowadays online, available to scholars from all over the world: writings, bills, speeches and public announcements, as well as a very big correspondence, his architectural drawings, his notebook notes. In Jefferson's "Notes on the State of Virginia" (1780), his only printed book, Jefferson offers an enlightening text on Virginia's state of affairs, a thorough analysis and description of Virginia's conditions at that time, of its prospects of change and urgent needs, including the renewal of architecture.

Which of the many episodes of Jefferson's life justifies much the title of your exhibition, explaining why Thomas Jefferson was an "Italian President", in your opinion?

At the inauguration of the exhibition, we organized a reading of some of Jefferson's writings. Among these, I can recall a description from his Travel Diary, a few lines written on the way back, before crossing the border while he was in Albenga, Liguria. Here, Jefferson describes Albenga as a beautiful place where anyone who wishes to retire at an advanced age should go: a fantastic place where the rhythm of the seasons is marked by the changing of landscape and colors, where nature offers a huge variety of products: "... Here are nightingales, beccaficas, ortolans, pheasants, partridges, quails, a superb climate, and the power of it changing from summer to winter at any moment, by ascending the mountains. The earth furnishes wine, oil, figs, oranges, and every production of the garden, in every season. The sea yields lobsters, crabs, oysters, thunny, sardines, anchovies ..."(From the Travel Diary, April 29, 1787)

It is a description of a place that seemed ideal to him: Jefferson loved the ancient architecture and the old continent, but criticized its cities as places of perdition, dangerous, dirty and noisy. Inspired by the principles of physiocracy, he dreamt of a rural America, although he knew very well that it could never be realized: he was very fascinated by the idea of maintaining uncontaminated Virgin's boundless spaces. Surely Jefferson was struck and influenced by the Italian history and culture, but landscapes, colors, fragrances, and agricultural resources of the area deeply fascinated him.

The topic of the relationship between Jefferson and Italy is vast and well-studied, but still open to multiple research projects, which hopefully can be conducted on new occasions of collaboration between Italian and American institutions.

You may be interested

-

An Unlikely Union: The love-hate story of Ne...

Award-winning author and Brooklynite Paul Moses is back with a historic yet dazzling sto...

-

Cathedral of St. John the Divine, Oratorio S...

For the first time ever, The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, in collaboration with the O...

-

Davide Gambino è il miglior "Young Italian F...

Si intitola Pietra Pesante, ed è il miglior giovane documentario italiano, a detta della N...

-

Garibaldi-Meucci Museum to Celebrate Ezio Pi...

On Sunday, November 17 at 2 p.m., Nick Dowen will present an hour-long program on the life...

-

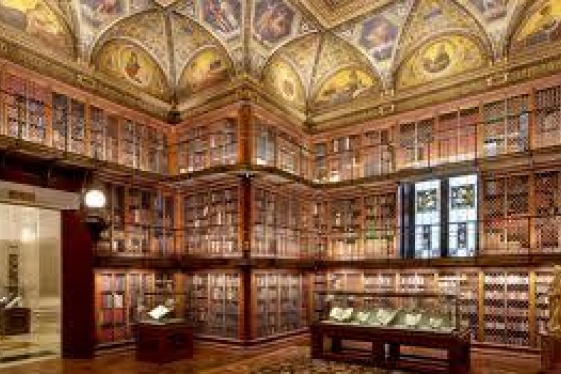

Italian Master Drawings From The Morgan (Onl...

The Morgan Library & Museum's collection of Italian old master drawings is one of the...

-

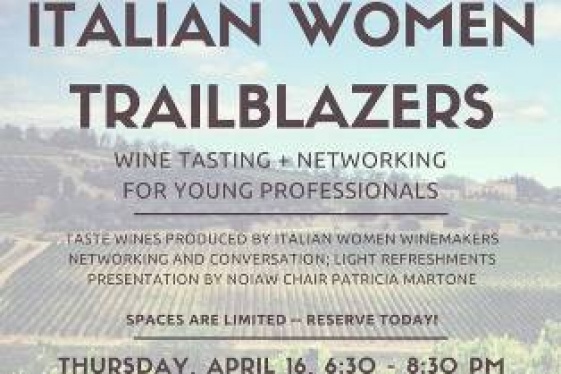

Italian Women Trailblazers - Young Professio...

April 16, thursday - 6,30 EDTAzure - New York, NY - 333 E 91st St, New York 10128Tick...

-

La Befana makes her way to the Garibaldi-Meu...

Saturday, January 10at 2:00pm - 4:00pm, Garibaldi-Meucci Museum 420 Tompkins Ave, Staten I...

-

Lecture and Concert that bring Italy to New...

Saturday, february 28 - 7 pm ESTChrist & Saint Stephen's Church - 120 W 69th St,...