Last October, during the visit of the President of the Italian Republic Sergio Mattarella to the White House, President Donald Trump said the following words: "The United States and Italy are bound together by a shared cultural and political heritage dating back thousands of years to Ancient Rome.” An uproar broke out, because some people wanted to believe that President Trump had made a gaffe: but it is clear that he was referring to ancient Rome and the influence it transmitted to the Founding Fathers of the United States.

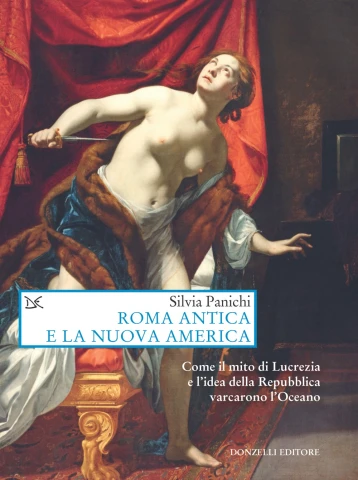

Indeed, twenty American states plus the District of Columbia have as their motto a Latin phrase: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Idaho, Kansas, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia. And of course, the symbol of the United States is an eagle, also symbol of the power of ancient Rome, the emperor and the empire; and the inscription "E pluribus unum" (Out of many one), also appears on American coins. In short, in this case the President of the United States was not wrong: well before last October, a very interesting book on this - “Roma Antica e la Nuova America” - was written by Professor Silvia Panichi. We welcome her on We the Italians.

The United States of America and ancient Rome: why did the founding fathers draw inspiration from the Roman Empire?

More than the Roman Empire, they were inspired by the heroes who founded the Roman Republic, because, like them, they fought a power that was presented as oppressive of freedom. England at the end of the eighteenth century was a constitutional monarchy, but it controlled the economy of the American colonies and imposed taxes on them that were perceived as deeply unjust.

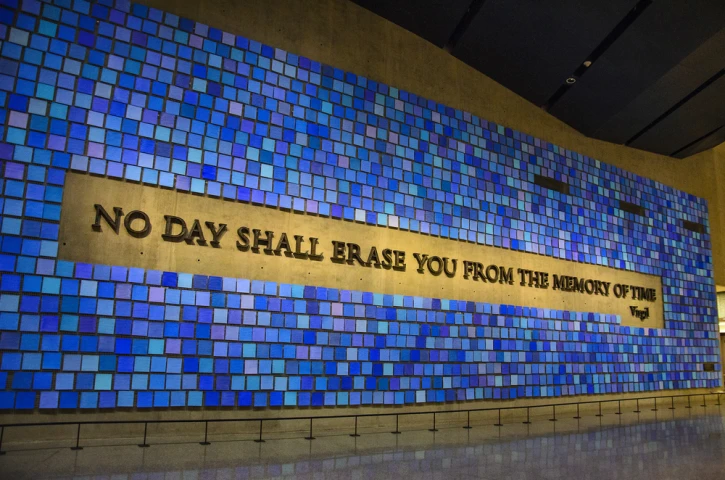

More generally, the ancient world was a shared point of reference: the Greeks and Romans could be cited as models of skill in military strategy; a large number of reforms, modes of governance and political strategies were identified in their historical events. And we could also refer to them for their ability to express passions and feelings. The recourse to the verses of ancient poets to comment on moments of joy or collective pain continues in today's America. In the memorial for the victims of September 11th we read one of the sentences that Virgil dedicates, in the Aeneid, to the death of Euryalus and Nisus: No day shall erase you from the memory of time (nulla dies umquam memori vos eximet aevo).

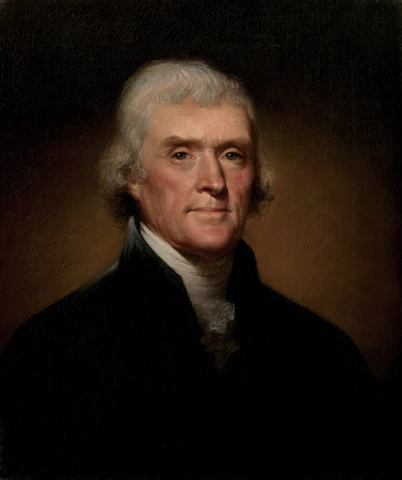

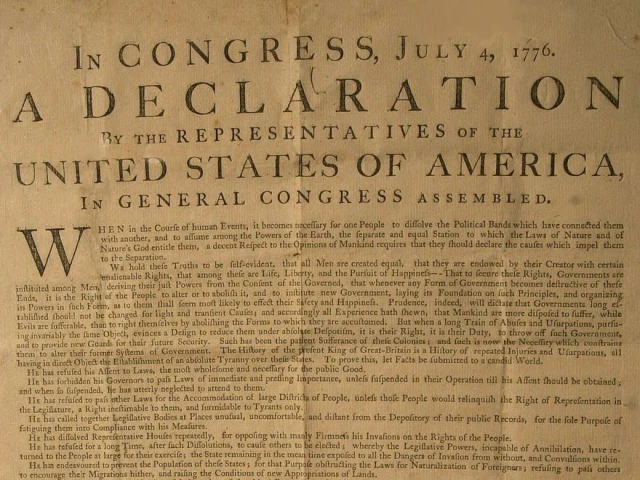

It seems to me that Thomas Jefferson was the most experienced connoisseur and admirer of the Rome of the past, also because he read Latin. Is it true that there is a quotation of Cicero in the Declaration of Independence?

Thomas Jefferson was a passionate lover of the classical tradition, as evidenced by his architectural achievements, his library, his mastery of ancient history. The residence of Monticello, which he worked on during his life, took on the plan and the elevation of the Venetian villas, which Palladio had created by harmonizing the decorative elements of Greek-Roman architecture with residential, agricultural and representative functions.

I have no precise quotations, but certainly in drawing up the Declaration of Independence it was important to know the most political works of Cicero, such as the De Legibus and the De Republica. But also by the reading of Tacitus, Livy, Plutarch, Seneca and others, ideas and models of behavior were drawn.

What are the decisions, actions and concrete places where this inspiration is visible to all?

There are many testimonies to the use of Roman models. I will remember just few of them.

The American generals, victorious in the battles that led to the defeat of the English in the War of Independence, were confronted with the Roman commanders most celebrated by historians, from Scipio the African to Paul Emilius.

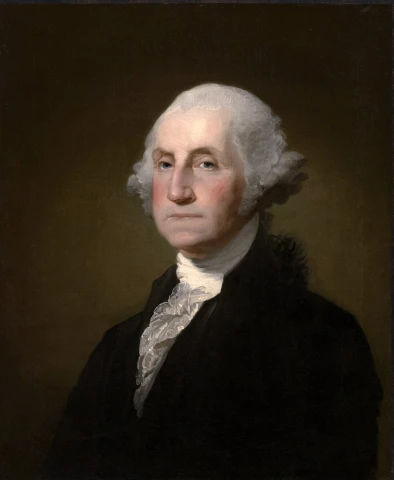

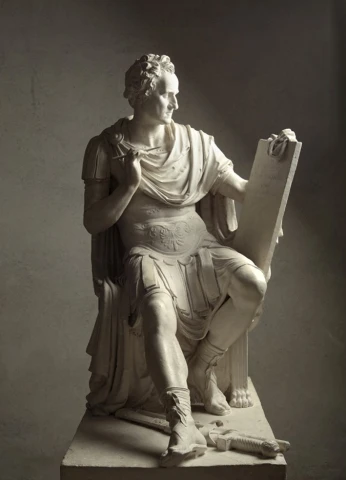

When the city of Raleigh, in North Carolina, wanted a statue of George Washington for its Capitol and Antonio Canova - the artist chosen at Jefferson's suggestion - represented him as Cincinnatus, it was clear that at least part of the American public was able to grasp the call to the Roman general who, like Washington, had stepped aside after having fulfilled his task.

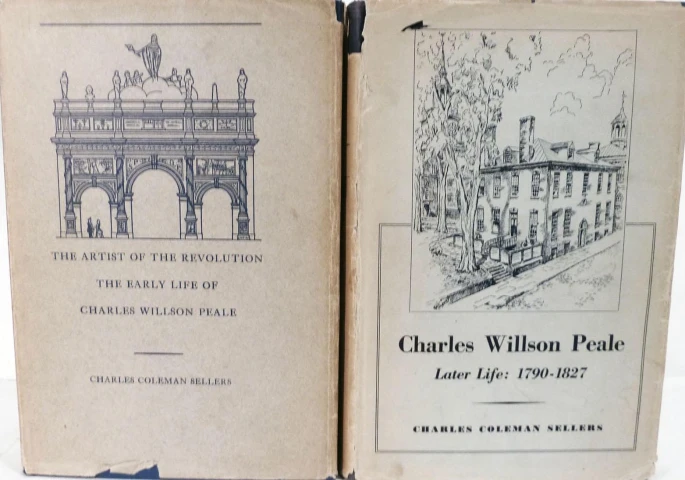

A watchmaker-painter from Maryland, Charles Willson Peale, created a triumphal arch in imitation of those raised in Rome, to celebrate the glorious conclusion of the American Revolution in Philadelphia.

The library of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, designed by Jefferson to testify to his confidence in public education, clearly recalls the architecture of the Pantheon, one of the best-preserved Roman buildings.

In the description of your book we read that never before, as at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, were cultural exchanges between the two sides of the Atlantic more intense and frequent...

Of course, mine is a somewhat paradoxical statement. There is no doubt that in our times it much easier to travel, just as it takes a moment to circulate news, ideas, publications. But even in an era in which all forms of contact could only be conveyed in very long times, it can be shown that there was a real mutual interest between peoples on both sides of the Atlantic, based on the feeling of a common cultural tradition.

This is demonstrated, for example, by the circulation of prints of works of art, but also the journeys of artists and writers; or the history of the French Lafayette, engaged in the American and French Revolution, or the same Jefferson, who before becoming President of the United States held positions in France, stayed in England and visited northern Italy.

That's why I liked to mention an amusing passage from Charles Dickens in his American Notes. At the end of his troubled Atlantic crossing in January, the great English writer thinks back to the words of a Scottish waitress who consoled his wife, tried by the stormy sea, reassuring her that a young mother on one side of the Atlantic is very close to her child left by the other, and that what seemed to the inexperienced a terrible journey, for the experts was only a little joke to be taken lightly!

What is the myth of Lucretia?

The story of the violence against Lucretia by the son of Tarquinio the Proud, which moreover contravenes the sacred bonds of hospitality and kinship, is told by historians as part of the final phase of the monarchy, where elements of truthfulness are mixed with legendary elaborations.

For its political value, given that the revenge demanded by the matron marks the beginning of the Roman Republic, it becomes an exemplary story; the American painter John Trumbull, inspired by the representation that had been given by the English painter Gavin Hamilton, also paints, at the end of the eighteenth century, the suicide of Lucretia, who does not want to survive her dishonor. And he thinks back to that story when he tells of the battles of the War of Independence.

The first series of eight small-format paintings that Trumbull dedicated to this saga is kept in the collection of Yale University. In the battles that tell of the transformation of his land into an independent nation, the painter, who in some cases had been a direct witness, constantly chooses to represent the death of a fighter in the arms of a companion, just as he had painted Lucretia who breathes into the arms of her husband, surrounded by men who would avenge her death.

There is the inspiration of ancient Rome for the new United States of America: but there is also that of George Washington for Vittorio Alfieri. So the influence travels on the Atlantic Ocean in both directions...

Vittorio Alfieri dedicates his tragedy Brutus I, the avenger of Lucretia, to George Washington, stating that only the name of the American general can be compared to the tragedy of the liberator of Rome. It was December 31st, 1788. Antonio Canova worked on the statue of Washington while somebody read aloud to him the History of the War of Independence of the United States of America by Carlo Botta, published for the first time in Paris in 1809. Artistic models, philosophical analyses, heroic biographies travelled from Europe to America, but also in the opposite direction. And that common cultural baggage helped the dialogue between distant worlds; one wonders if these same worlds, now very close, can do the same.

In your book you reveal the traces of classicism scattered among art, literature and cinema in America...

Elements taken from the classical world also impose themselves where we could least expect them: being passionate about cinema, I enjoyed looking for epic and tragic ideas in “Stagecoach” and “High Noon”, two wonderful films that do not deal with ancient history: and I found them not only in the plots, but also in the quotations of some of the protagonists. I also believe that we all have before our eyes the facade built like that of an ancient temple, characteristic of many villas in the southern states, in one of the initial scenes of “Gone With the Wind”.

However, we must not forget that even in our national anthem the first character to appear is Scipio, by whose helmet Italy is encircles its head. This was written by Goffredo Mameli, who died in his twenties, on July 6th, 1849, from his wounds suffered defending the Roman Republic from the invasion of the French army.

Are there still explicit references to ancient Rome in the United States today?

This was not the subject of my book. But of course many American capitols reveal the classical imprint of their architecture; a large number of valuable archaeological finds, purchased in times of lesser protection, are the subject of important studies and are the attraction of the museums that preserve them. And very successful films have referred to key episodes in ancient history, obviously interpreting them according to cinematic needs.

The reference to Rome is still frequent in the considerations of politicians, including the Presidents. In the introduction to my book I recalled when John Kennedy pronounced the famous phrase "Ich bin ein Berliner", having previously made it clear that two thousand years earlier the greatest pride had been being able to affirm "Civis Romanus sum".

But the reference to the Greco-Roman tradition is also revealed where you least expect it. A few days ago, during a visit to the beautiful new Whitney Museum, I crossed the image of some classical columns. It was one of the many works of the mid-sixties that Roy Lichtenstein, one of the founders of Pop Art, created taking inspiration from a postcard of the temple of Apollo in Corinth.

Nel corso della visita del Presidente della Repubblica Italiana Sergio Mattarella alla Casa Bianca dello scorso Ottobre, il Presidente Donald Trump ha detto le seguenti parole: “The United States and Italy are bound together by a shared cultural and political heritage dating back thousands of years to Ancient Rome.” Si è scatenato un putiferio, perché alcuni hanno voluto ritenere che il Presidente Trump avesse fatto una gaffe: ma è evidente che si riferiva all’antica Roma e all’influenza che essa ha trasmesso ai Padri Fondatori degli Stati Uniti.

D’altronde ben venti Stati americani più il District of Columbia hanno come motto una frase latina: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Idaho, Kansas, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia. E ovviamente, gli Stati Uniti hanno nel loro simbolo un’aquila, simbolo del potere dell'antica Roma, dell'imperatore e dell'impero, e la scritta “E pluribus unum” (Dai molti uno), che compare anche sulle monete americane. Insomma, in questo caso il Presidente degli Stati Uniti non aveva torto: su questo, ben prima dello scorso Ottobre, ha scritto un bel libro - “Roma Antica e la Nuova America” - la Professoressa Silvia Panichi, alla quale diamo il benvenuto su We the Italians.

Gli Stati Uniti d’America e Roma antica: perché i Padri fondatori si ispirarono all’Impero romano?

Più che all’Impero romano si ispirarono agli eroi che avevano fondato la Repubblica romana, perché, come loro, combattevano un potere che era presentato come oppressivo della libertà. L’Inghilterra della fine del Settecento era una monarchia costituzionale, ma controllava l’economia delle colonie americane a cui imponeva tasse percepite come profondamente ingiuste.

Più in generale, il mondo antico costituiva un punto di riferimento condiviso: i Greci e i Romani potevano essere citati come modelli di abilità nella strategia militare; un gran numero di riforme, modalità di governo e strategie politiche venivano individuate nelle loro vicende storiche. E ci si poteva riferire a loro anche per la capacità di esprimere passioni e sentimenti. Il ricorso ai versi dei poeti antichi per commentare momenti di gioia o dolore collettivo continua nell’America di oggi. Nel memoriale per le vittime dell’11 settembre si legge una delle frasi che Virgilio dedica, nell’Eneide, alla morte di Eurialo e Niso: nessun giorno potrà mai strapparvi a un memore tempo (nulla dies umquam memori vos eximet aevo).

Mi sembra che fra tutti, Thomas Jefferson fosse il più esperto conoscitore e ammiratore della Roma di un tempo, anche perché leggeva il latino. E’ vero che c’è una citazione di Cicerone nella Dichiarazione di Indipendenza?

Thomas Jefferson fu un appassionato cultore della tradizione classica, come è testimoniato dalle sue realizzazioni architettoniche, dalla sua biblioteca, dalla sua padronanza della storia antica. La dimora di Monticello, a cui lavorò nel corso della vita, riprendeva la pianta e l’alzato delle ville venete, che Palladio aveva realizzato armonizzando gli elementi decorativi dell’architettura greco -romana con funzioni abitative, agricole e di rappresentanza.

Non mi risultano citazioni puntuali, ma, sicuramente, nel redigere la Dichiarazione d’Indipendenza fu importante la conoscenza delle opere più politiche di Cicerone, come il De Legibus e il De Republica. Ma anche dalla lettura di Tacito, Livio, Plutarco, Seneca ed altri, venivano tratti spunti di riflessioni e modelli di comportamento.

Quali sono le decisioni, le azioni e i concreti luoghi in cui questa ispirazione è visibile a tutti?

Molte sono le testimonianze del ricorrere a modelli romani. Ne ricordo alcune.

I generali americani, vittoriosi nelle battaglie che portano alla sconfitta degli Inglesi nella Guerra d’Indipendenza, venivano confrontati con i comandanti romani più celebrati dagli storici, da Scipione l’Africano a Paolo Emilio.

Quando la città di Raleigh, nel nord Carolina, volle una statua di George Washington per il suo Campidoglio e Antonio Canova - l’autore prescelto su suggerimento di Jefferson - lo rappresentò nelle vesti di Cincinnato, era evidente che almeno parte del pubblico americano era in grado di cogliere il richiamo al generale romano che, come Washington, si era fatto da parte dopo aver adempiuto al suo compito.

Un orologiaio-pittore del Maryland, Charles Willson Peale, creò un arco di trionfo a imitazione di quelli alzati a Roma, per celebrare a Philadelphia la gloriosa conclusione della Rivoluzione americana.

La biblioteca dell’Università della Virginia a Charlottesville, progettata da Jefferson a testimonianza della sua fiducia nell’istruzione pubblica, richiama in modo evidente l’architettura del Pantheon, uno degli edifici romani meglio conservato.

Nella descrizione del suo libro è scritto che mai come a cavallo tra Sette e Ottocento intensi e frequenti furono gli scambi culturali tra le due sponde dell’Atlantico...

Naturalmente la mia è un’affermazione per certi versi paradossale. E’ indubbio che in questi nostri tempi è tanto più facile viaggiare, così come basta un attimo per far circolare notizie, idee, pubblicazioni. Ma anche in un’epoca in cui ogni forma di contatto poteva essere veicolata solo in tempi lunghissimi, si può dimostrare come ci fosse un vero interesse reciproco tra i popoli sulle due sponde dell’Atlantico, fondato sul sentimento di una comune tradizione culturale.

Lo dimostra, ad esempio, la circolazione delle stampe di opere d’arte, ma anche i viaggi di artisti e letterati; o la storia del francese Lafayette, impegnato nella rivoluzione americana e in quella francese, o dello stesso Jefferson che prima di diventare presidente degli Stati Uniti ebbe incarichi in Francia, soggiornò in Inghilterra e visitò l’Italia settentrionale.

Per questo mi è piaciuto citare un divertente passo di Charles Dickens contenuto nelle sue American Notes. Alla fine della sua tribolata traversata atlantica compiuta in gennaio, il grande scrittore inglese ripensa alle parole di una cameriera scozzese che consolava sua moglie, provata dal mare in tempesta, rassicurandola sul fatto che una giovane madre su una sponda dell’Atlantico è vicinissima al suo bambino lasciato dall’altra, e che quel che agli inesperti pareva un viaggio terribile, per gli iniziati non era che uno scherzetto da fischiettarci sopra!

Cos’è il mito di Lucrezia?

La vicenda della violenza su Lucrezia da parte del figlio di Tarquinio il Superbo, che oltretutto contravviene ai sacri vincoli dell’ospitalità e della parentela, è narrata dagli storici nell’ambito della fase finale della monarchia, dove elementi di veridicità si mescolano a elaborazioni leggendarie.

Per la sua valenza politica, visto che la vendetta chiesta dalla matrona segna l’inizio della Repubblica romana, diviene una storia esemplare; anche il pittore americano John Trumbull, ispirandosi alla rappresentazione che ne aveva dato il pittore inglese Gavin Hamilton, dipinge, alla fine del Settecento, il suicidio di Lucrezia, che non vuole sopravvivere al suo disonore. E ripensa a quella storia quando racconta le battaglie della guerra di Indipendenza.

La prima serie di otto quadri di piccolo formato che Trumbull dedicò a questa saga è conservata nella collezione della Yale University. Nelle battaglie che raccontano la trasformazione della sua terra in nazione autonoma, il pittore, che in alcuni casi era stato un testimone diretto, sceglie costantemente di rappresentare la morte di un combattente tra le braccia di un compagno; così come aveva dipinto Lucrezia che spira tra le braccia del marito, circondata dagli uomini che ne avrebbero vendicato la morte.

C’è l’ispirazione dell’antica Roma per i nuovi Stati Uniti d’America: ma c’è anche quella di George Washington per Vittorio Alfieri. Dunque la contaminazione viaggia sull’Oceano Atlantico in entrambe le direzioni…

Vittorio Alfieri dedica la sua tragedia Bruto I, il vendicatore di Lucrezia, a George Washington, affermando che solo il nome del generale americano può essere comparato alla tragedia del liberatore di Roma. Era il 31 dicembre 1788. Antonio Canova lavorava alla statua di Washington facendosi leggere ad alta voce la Storia della guerra d’Indipendenza degli Stati Uniti d’America di Carlo Botta, pubblicata per la prima volta a Parigi nel 1809. Modelli artistici, analisi filosofiche, biografie eroiche viaggiavano dall’Europa all’America, ma anche in senso contrario. E quel comune bagaglio culturale aiutava a dialogare mondi distanti; viene da chiedersi se questi stessi mondi, oggi ormai vicinissimi, riescono a fare altrettanto.

Nel suo libro lei ci rivela le tracce della classicità disseminate tra arte, letteratura e cinema in America...

Elementi tratti dal mondo classico si impongono anche dove meno potremmo aspettarcelo: essendo appassionata di cinema mi sono divertita a cercare spunti epici e tragici in “Ombre rosse” e “Mezzogiorno di fuoco”, due film meravigliosi ma che non trattano di storia antica: e ne ho trovati non soltanto nelle trame, ma anche nelle citazioni di alcuni dei protagonisti. Credo poi che tutti abbiamo davanti agli occhi la facciata costruita come quella di un tempio antico, caratteristica di molte ville degli stati del Sud, in una delle scene iniziali di “Via col vento”.

Non dobbiamo, però, dimenticarci che anche nel nostro inno nazionale il primo personaggio che compare è Scipione, del cui elmo l’Italia si cinge la testa. Lo aveva scritto Goffredo Mameli, morto ventenne, il 6 luglio del 1849, per le ferite riportate nella difesa della Repubblica romana dall’invasione dell’esercito francese.

Esistono ancora richiami e riferimenti espliciti alla Roma antica negli Stati Uniti di oggi?

Questo argomento non è stato oggetto del mio libro. Ma certo molti Campidogli americani rivelano l’impronta classica della loro architettura; un gran numero di reperti archeologici di valore, acquistati in epoche di minor tutela, sono oggetto di studi importanti e costituiscono l’attrazione dei musei che li conservano. E film di grande successo hanno fatto riferimento a episodi chiave della storia antica, interpretandoli naturalmente secondo le esigenze cinematografiche.

Il richiamo a Roma è ancora frequente nelle considerazioni degli uomini politici, compresi i Presidenti. Nella introduzione del mio libro ho ricordato di quando John Kennedy pronunciò la celebre frase “Ich bin ein Berliner”, avendo chiarito in precedenza che duemila anni prima il più grande orgoglio era stato poter affermare “Civis Romanus sum”.

Ma il richiamo alla tradizione greco-romana si rivela anche dove meno te lo aspetti. Qualche giorno fa, in una visita al nuovo, bellissimo Whitney Museum, ho incrociato l’immagine di alcune colonne classiche. Si trattava di uno dei molti lavori della metà degli anni Sessanta che Roy Lichtenstein, uno dei fondatori della Pop Art, realizzò ispirandosi a una cartolina del tempio di Apollo a Corinto.