The year 2026 marks the bicentenary of the birth of Carlo Collodi, pseudonym of Carlo Lorenzo Filippo Giovanni Lorenzini, journalist and writer.

Collodi, who was born in Florence on November 24, 1826, decided to take the name of his mother's hometown, Angiolina Orzali, as his pen name.

The young man, inspired by strong republican and Mazzinian ideals, took part in the Risorgimento revolts of 1848-49 when he was just over twenty years old.

In his early days as a journalist, he devoted himself to describing the bizarre and amusing aspects of Tuscany at the time, with entertaining coffee-house stories and brilliant linguistic inventions.

Stimulated by these early creative experiences, he exercised his ability to bring contemporary life to life through his poetry.

In 1956, at the age of just thirty, with “Un romanzo in vapore, Da Firenze a Livorno” (A Novel on Steam, From Florence to Livorno), he was among the first to highlight the technological innovation brought about by the railway.

As an official of the newly formed unified state, he translated Perrault's fairy tales and then worked on various educational books for schools, thus embarking on the path that would lead to his consecration.

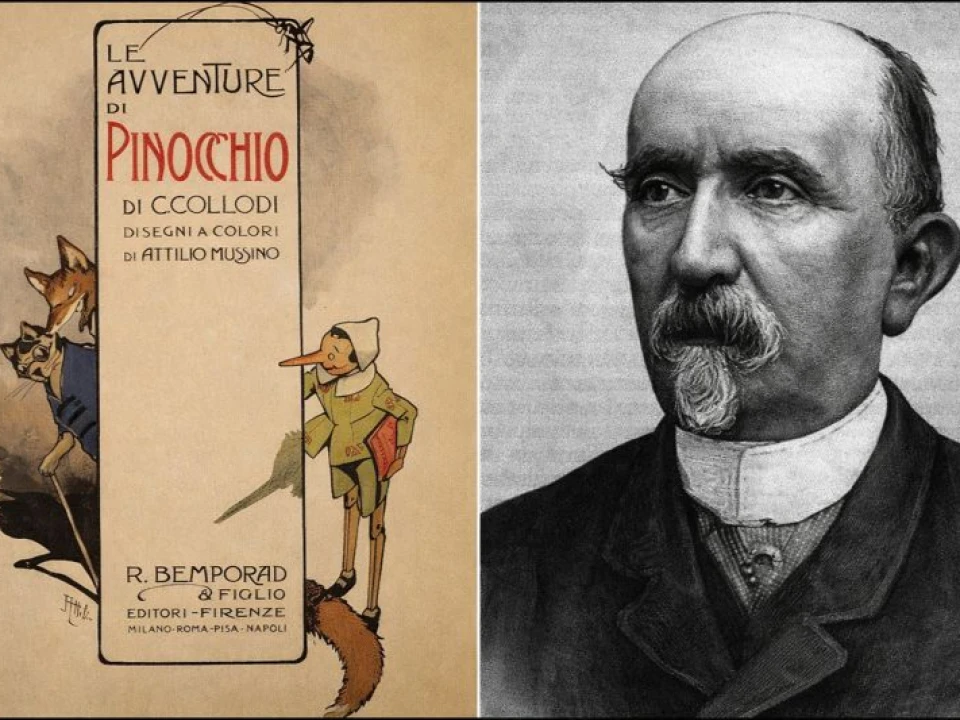

In fact, after Giannettino (1875) and Minuzzolo (1877), he wrote his masterpiece “The Adventures of Pinocchio,” which first appeared in the “Giornale dei bambini” in 1881, under the title “The Story of a Puppet,” ending with the fifteenth chapter.

In the following months, Collodi resumed work on the book, which he completed in 1883, giving it its definitive title.

Recent studies show that “The Adventures of Pinocchio” is the most widely read Italian book in the world, with 669 translations into 192 languages and dialects.

But the work is much more than a great literary success.

The book gave rise to a character who became a masterpiece of design, a concentration of meanings, a universal figure: the puppet Pinocchio, with his proverbial and distinctive long nose.

So much so that at the end of 2023, on the 140th anniversary of the book's first edition, the ADI Design Museum in Milan dedicated an important exhibition to the puppet, entitled “Carissimo Pinocchio” (Dearest Pinocchio).

The project, curated by Giulio Iacchetti and designed by Matteo Vercelloni, saw the contribution of Marco Belpoliti for the historical iconographic selection and Federica Marziale Iadevaia for the graphic component.

The cover of the magnificent catalog, published by ADIper, featured an unpublished drawing by the centenarian artist Attilio Cassinelli.

Upon entering the museum, visitors were greeted by the historical-iconographic section, in which Marco Belpoliti used photographic reproductions of drawings, book covers, magazines, and advertising posters to offer a broad overview of Pinocchio's publishing success.

There were also references to the first films and plays dedicated to the famous puppet, such as the 1952 Italian comedy Totò a colori, in which Prince De Curtis gave a stunning mechanical interpretation of his movements; or Carmelo Bene's play of the same name, which premiered in 1961, was adapted for radio in 1974, and then for television in 1999.

The heart of the project was the second section, which presented 62 new projects by 31 product designers and 31 graphic designers who, at the curator's invitation, had tried their hand at creating three-dimensional and two-dimensional versions of Pinocchio.

Regarding the relationship between Pinocchio and design, Giulio Iacchetti wrote in his catalogue essay: “Dear Pinocchio, I think I can say that you definitely have a place in this story, which is the story of Italian design, and I'll tell you why.

Have you ever looked at yourself in the mirror? You are a simple but highly effective combination of a few geometric shapes: a cylinder, a sphere, the cone of your hat, and of course the pointed, thin protrusion of your nose. Your iconic power is directly proportional to your immediate formal recognizability. Yes, because you are an icon symbolizing Italianness, just like the Tizio lamp, the Fiat Panda, or the Olivetti typewriter!

From such a simple formal recipe, countless versions of you have sprung up over the years, both in terms of graphics and shape: all different, but all clearly traceable back to the archetype (which would be you).

Pinocchio, with his unmistakable silhouette, original design, and proverbial long nose, has become a global icon.

His story and characters have even undergone various adaptations in different countries, with the aim of making them as relevant as possible to the local reality.

In a Persian edition, for example, the Talking Cricket becomes the Talking Cockroach, due to the scarcity of crickets in Iran.

A Swiss edition from 1936 offers a Swiss variation on the story: when Pinocchio climbs onto a pigeon, which will take him to the sea, the bird at one point deviates and flies over mountains and glaciers typical of the Alps.

In Russia, also in 1936, Buratino appeared, whose story closely resembles that of Pinocchio: in the second part of the text, the protagonist becomes a sort of socialist Pinocchio, who tries with his companions to emancipate themselves from the oppressive Mangiafuoco.

In Africa, Pinocchio becomes black, like Geppetto, who is described at work using tools typical of African craftsmen.

In Chile, during the dictatorship, the posters put up by the opposition significantly featured “Pinocho”: a lying Pinochet.

In short, the figure of Pinocchio seems today to be more relevant than ever to the dictates of the most modern and advanced design, combining extreme stylistic originality with a distinctive and iconic semantic value.