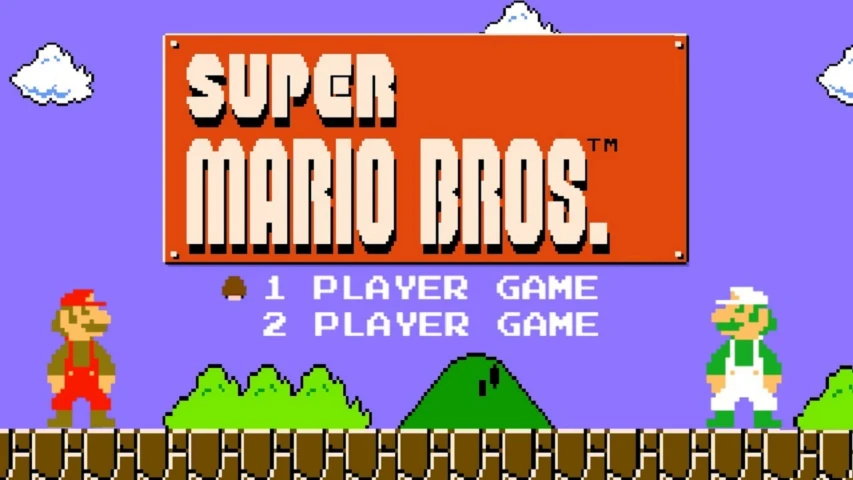

In September - forty years ago - Nintendo released a video game that changed the history of global entertainment. It was called Super Mario Bros., and it featured an Italian American plumber who had already appeared in a previous game, Donkey Kong (1981). That game was so successful that in 1983 Nintendo launched Mario Bros. But it was in 1985 that Mario - now Super Mario - became a worldwide phenomenon.

To mark the fortieth anniversary of this global success, We the Italians is pleased to host Professor Marco Benoît Carbone, author of one of the most complete and insightful essays ever written on Super Mario: Olive Face, Italian Voice: Constructing Super Mario as an Italian-American (1981-1996).

Professor Carbone, I’d like to start by asking how your interest in the character of Super Mario began.

My first memory of this character goes back almost forty years, to an elementary school party. I remember everyone’s eyes fixed on a gray box, which I soon discovered was a Nintendo console, and a single obsessive chant: “Let’s play Super Mario.” Seeing characters that could move freely on the TV screen was fascinating. Then I became curious about the fact that the character had an Italian name.

Several years later, I learned that Nintendo games came from Japan. So I began to wonder what the story behind Super Mario was. I think it was in those moments that a certain vague curiosity began to take shape. Many years after that, it grew into a historical interest in a pop icon that has reached the popularity - and perhaps, in part, the cultural significance - of a Donald Duck or a Mickey Mouse.

In your work, you describe the three main stages in the writing of the character Super Mario, from his beginnings to his evolution…

I simply outlined - without intending to be too schematic - a few stages in the development of a long-lived and now multifaceted intellectual property.

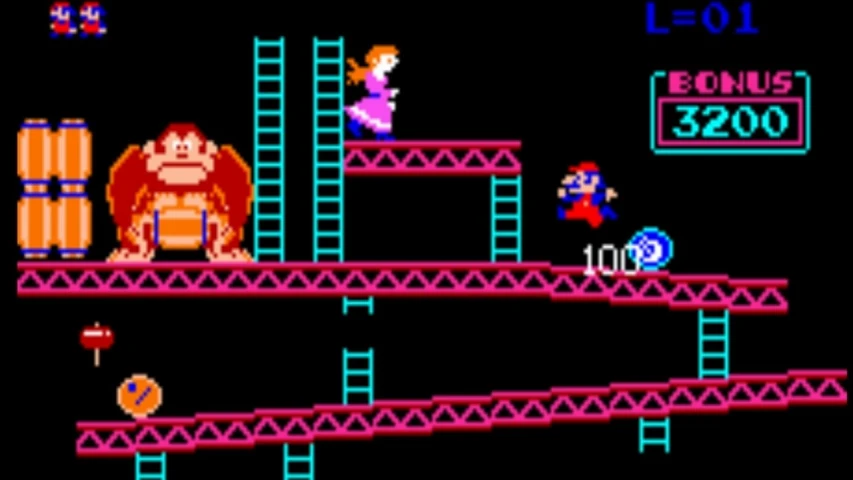

In the early 1980s, Super Mario was a very generic Mediterranean character: an Italian American, as that identity might have been perceived from the perspective of a Japanese creator who loved comics and cinema - Shigeru Miyamoto. This artist had been hired by Nintendo, a company that had originally produced playing cards, some under license from Walt Disney.

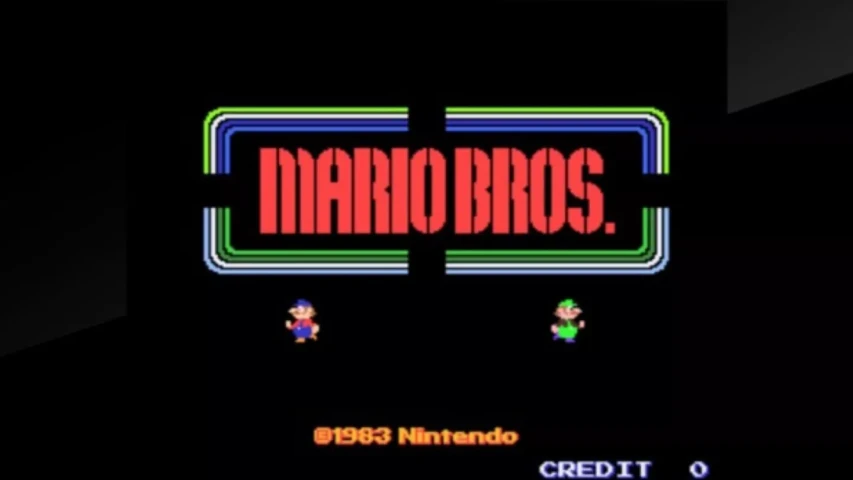

Miyamoto set out on a special mission: to transform the company’s video games, based in Kyoto, into experiences that weren’t just about skill and challenge, but revolved around stories, gags, and memorable characters. He worked on several games that would prove revolutionary in terms of design and character presentation: Donkey Kong, Mario Bros., and later Super Mario Bros., which had an explosive commercial impact.

At first, we control Jumpman. He later takes the name Mario - perhaps because Miyamoto was looking for a character who wasn’t too Japanese or too stereotypical, someone recognizable and funny both in Japan and in the United States, a market Nintendo was strongly targeting. As for the Italian connection, maybe Miyamoto had seen The Godfather by Francis Ford Coppola, or perhaps he had been exposed to the classic imagery of the Italian immigrant working-class man with suspenders and a flat cap - a figure often seen in films and animated productions.

There was probably also a broader cultural context dating back to the postwar years. If the goal was to create a likable, slightly quirky, and original character, then an Italian one might work. Japan viewed Italy as a particular kind of “West”: not the American superpower or the former British Empire, not the industrial rival Germany or the proud France. Perhaps Italy was different, as some scholars like Toshio Miyake have suggested - it was a failed former ally of World War II, and a country perceived as tied to folklore, cuisine, art, traditions, and family values, all seen as positive traits in Japan. In any case, the vagueness of the Italian reference made it intriguing.

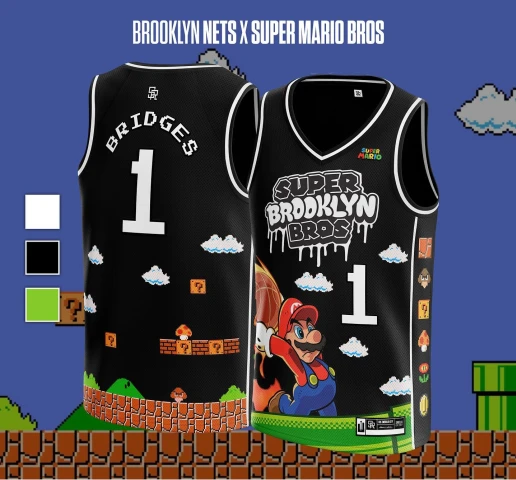

Moreover, as I mentioned, Italians were well known in American culture - the market in which Nintendo had strong commercial interests. When Super Mario arrived in the United States, the character became a success, perhaps beyond Nintendo’s own expectations. Maybe this was because, in that multiethnic, immigrant nation, Italian Americans were a very recognizable demographic group, turning Mario into a pop phenomenon. Everyone wanted to license the character’s memorable face for all kinds of merchandise: pasta boxes, pins, stickers, telephones, detergents, comic books, cartoons, and TV shows - where his “ethnic” traits were often exaggerated.

The Japanese creators took note of this success. Toward the end of the 1980s, they updated Super Mario’s model sheet (a document describing the character for production and creative use), specifying that he was Italian American - more precisely, a New Yorker from Brooklyn.

That trait would continue to define the character to this day, although in later decades the company chose to handle Mario’s identity with great flexibility. In some games, his only Italian feature is his name. Mario became part of a vast, Disney-like universe of characters encompassing hundreds of games and products. Super Mario is Nintendo’s most successful brand, and the character must remain well-defined enough to be memorable, yet vague enough to adapt from one product to another - from a classic platform game to a tennis match.

Nonetheless, in many instances, his Italian identity becomes more pronounced: Mario rides a Vespa, utters phrases like “mamma mia” and “it’s-a-me, Mario” (with that trademark schwa between vowels, straight from the Italenglish cliché), and dreams of plates of spaghetti, pici, ravioli, and lasagna.

Fine modulo

Your research focuses particularly on voice, dubbing, and accent. Could you tell us more about this topic?

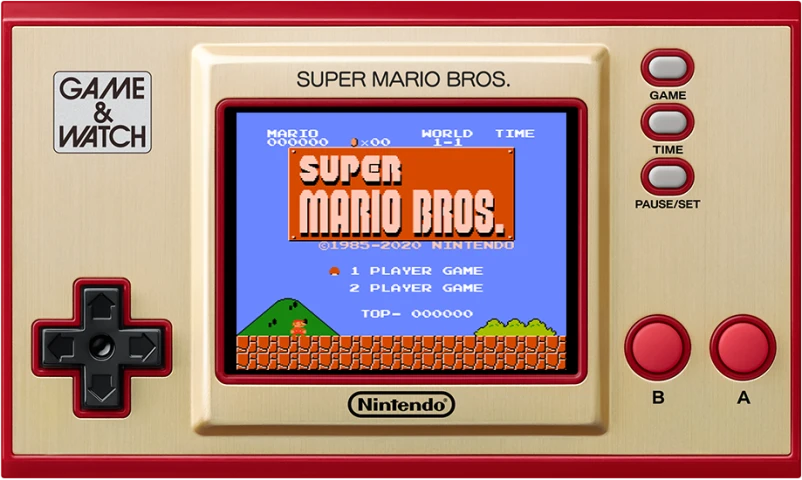

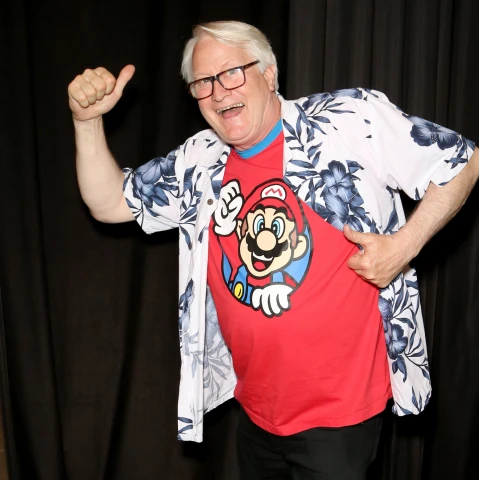

Around the mid-1990s, new media and technologies were evolving. Orchestral music, voice acting, and recorded dialogue started to become potential selling points because they made characters feel more alive and dynamic. Nintendo began experimenting with giving Super Mario a voice, and after a few trials in niche products, decided to make it official in Super Mario 64.

That voice was provided by actor Charles Martinet, who - although recently replaced - remains the voice most audiences associate with Mario. Martinet is a seasoned performer, and when it came time to experiment with what kind of voice Mario should have, he began with the idea of an Italian accent. In shaping it, he drew on a well-established repertoire of national “types” (and stereotypes) that actors and voice performers had long used for cartoon characters - and not just cartoons. Ever since the advent of sound cinema, there have been fascinating acting manuals filled with stereotyped instructions on how to reproduce the speech patterns of various ethnicities and nationalities.

The result was a kind of hyperreal Italian - warm and humorous - that playfully exaggerated traits English speakers tend to associate with Italians: the rolled r, the inserted vowel in it’s-a-me, and a certain musical rhythm.

What’s the difference between this and Wiseguy English, the cadence used by many Italian American film characters that shaped the popular image of Sicilian-accented Italian Americans in flat caps?

Before Martinet, there had been a few attempts using deeper, more adult male voices with accents typical of New Jersey or nearby areas. But Martinet struck a unique balance by blending two accent types. The first is that of a second-generation Italian American - the kind you hear in movies, especially gangster films - which could be described as an ethnically accented native English. The second is a deliberately and playfully ungrammatical inflection, like that of a non-native speaker, delivered in a bright, childlike register, as you’d expect from a joyful, cartoonish character with a neotenic look.

The mix turned out to be a huge success - and it became the standard for the Super Mario voice.

Fine modulo

What is the relationship between Super Mario and the stereotypes and clichés that have always surrounded Italian Americans?

When Super Mario made his way to the United States, a flood of licensed products followed. Some of these were video games - and in those cases, Nintendo maintained relatively tight control over how its characters were portrayed, keeping them within the boundaries of products designed to emphasize cultural indeterminacy and a whimsical, fairy-tale tone meant to appeal to audiences all over the world. In other cases, such as the television series produced in the U.S., the fact that they were external productions led to more localized cultural portrayals.

As a result, a few old stereotypes resurfaced - though in a lighthearted and harmless way. In the TV series The Super Mario Bros. Super Show (1989), a mix of animation and live action, Mario and Luigi are portrayed as loud, boisterous, working-class Italians obsessed with food - a familiar trope in Anglophone popular culture. In some episodes of the same series, there are “turf war” scenes between cartoonish factions where Mario and his friends wear pinstripe suits, along with other visual references that risk evoking the image of the Italian American gangster - a figure that has long shaped portrayals of Italians in the U.S. (drawing criticism from organizations like the Italian Anti-Defamation League, but also contributing to the enduring and controversial glamour of New Hollywood films).

In any case, a few traces of stereotyping even seeped into the localization of the games themselves. The evil little mushrooms Mario crushes in the original Japanese version were called kuribō; in English, they became the “Goombas,” derived from “goombah” or “coombah.” This slang comes from regional dialects spoken in Italian American communities - compare, cumpari, cumpà. In the U.S., it could mean both “friend” and, unfortunately, “neighborhood gangster.”

In your essay, you introduce the concepts of “oliveface” and “olivevoice.” What do you mean by that?

They’re two terms I use to discuss how cultural industries - such as film, media, and even video games - have codified Mediterranean characters through an ethnic lens: that of the olive, or olive-toned identity. The “olive face” is that of the typical or stereotypical Mediterranean character - darker skin, prominent features, body hair, passionate temperament, and other cultural projections and expectations. “Olive voice,” by metaphorical extension, refers to the way of speaking a second language with the accent of a Mediterranean character.

When Mario was first given a spoken voice, Nintendo hired someone who neither spoke Italian nor was of Italian descent. The actor, therefore, performed the voice from outside the culture. To do so, he drew upon established cues for how an “Italian” should sound in a cartoon or similar medium. These cues weren’t just informal conventions - they were also reflected in acting manuals of the time, which offered precise guidance on how to reproduce “foreign” accents. This reflected how Anglophone culture perceived non-native languages as something minor, easily reduced to a few recognizable traits.

Historically, such clichés provided actors and voice performers with “economical” formulas: the Mediterranean character should have this olive complexion, should pronounce English with an Italian (or Greek) accent; perhaps they love olive oil, pizza, and pasta - just like our neighbor, our friend who runs the Italian restaurant, or like the Super Mario from the TV series.

The oliveface character, then, displays recognizable traits believed to belong to their group - positive or negative - which may be internalized or rejected by members of that group themselves. Stereotypes, in fact, pose a potential “threat” to those being represented (hence the term stereotype threat): according to such generalizations, all Italians should be dark-haired, should speak in a certain way, should have a certain personality, should love pasta, should share the same culture and history. But what if that’s not true?

Cultural industries and media have always been central to these now widely debated processes - from issues of wartime propaganda to contemporary questions of diversity in cinema. My formulation draws on Black theory, a field that critically examines the power of cultural industries to create symbolic realities with significant political effects. For centuries, Black and Indigenous identities have suffered simplifications, caricatures, and degrading practices such as blackface, which reduced them to comic stereotypes in stories where they were objects of ridicule.

By talking about oliveface and olivevoice, I didn’t intend to draw an exact parallel between that long history of abuse and degradation and the Italian or Mediterranean experience - these are very different stories, even though Italian identities have historically occupied a complex place within the dominant American notion of “whiteness.” My goal was simply to focus on the representational processes that show clear parallels: the communication of a stylized, simplified identity.

Super Mario is an Italian American plumber from Brooklyn, starring in games, movies, ads, and TV shows. What impact has he had on American and Italian American youth culture?

A remarkable impact - because, as I mentioned earlier, Super Mario has become a pop icon capable of transcending the world of video games alone.

In the United States, Italian Americans are a recognizable and well-loved group. During the 1980s - and especially the 1990s - Italy itself was becoming globally recognizable thanks to Made in Italy: fashion, food, automotive design, art. People spoke of an “Italy boom” in many parts of the world, when everyone began to celebrate Italian cuisine, pasta, wine, and opera music. Being Italian was, for a long time, hip - and at times, even fashionable.

This definitely influenced the character’s success. However, as I mentioned, there’s been a transformation in the way Super Mario and other characters express their “Italian-ness.” In recent years - perhaps over the past decade - the Japanese parent company has taken a much more careful and strategic approach to managing its assets. Now, the most diverse products show a much greater visual and thematic consistency than in the past. The animated Super Mario we see in theaters today is a very coherent extension of the current video game version - he has the same face, lives in the same worlds, and is essentially the same character.

In short, it’s unlikely we’ll ever see another movie like the one starring Bob Hoskins as the stocky Italian plumber (Super Mario Bros., 1993), which had little to do with the cartoonish video games of the time - or another TV show featuring Mario and Luigi as middle-aged, loud, and jokey plumbers, like in the television series of the 1980s.Fine modulo

Forty years after the release of Super Mario Bros., why do you think this character has enjoyed such extraordinary success?

It’s certainly a combination of factors - perhaps, taken together, difficult to decode or even impossible to fully grasp - though we can try to identify a few of them.

Without a doubt, Super Mario is synonymous with and a guarantee of high-quality video games. In some cases, these games have represented true turning points in the history of design. Thanks to them, at certain moments in time, the company itself became synonymous with video games. This success is transgenerational: today’s products also sell the nostalgia of those who grew up with them - people who now buy the new versions for their own sons and daughters.

Many of the games starring Super Mario embody a philosophy aimed at transporting players into a carefree dimension. They are almost always suitable for all ages and reflect the company’s historic ability to harmonize the many capacities of the video game medium - which is at once science and art, combining the thrill of control with immersion in imagery, sound, and story. Super Mario represents a universal fantasy: running through meadows, jumping across floating platforms, soaring through the air, swimming underwater. These mediated activities perhaps respond, on a psychological level, to the energetic drive of childhood - to that happy oasis theorized by Eugene Fink, who reflected on the essential existential role of play in human life.

Super Mario’s face - with its now distinctly youthful, rounded features - his gentle temperament, and his positive characterization have made him a versatile figure through whom players can forget the constraints of daily life, of the body, and of age. Mario is an avatar that fulfills, in an almost universal way, our Peter Pan syndrome.

Finally, perhaps part of his appeal really does lie in his Italian-ness: many of the positive stereotypes about Italy portray us as lovable, cheerful, loyal, passionate, and lovers of beauty and goodness - friendly and harmless. So, Super Mario may appear not only exotic yet familiar, but also capable of evoking some of those long-standing, romantic, and imprecise - yet deeply desirable - ideas about Italy.

Nel Settembre di 40 anni fa la Nintendo pubblicò un videogioco che ha cambiato la storia dell’entertainment mondiale. Si chiamava Super Mario Bros. E aveva come protagonista un idraulico italoamericano che già nel 1981 era stato un personaggio di un precedente videogioco, Donkey Kong, tanto apprezzato che poi nel 1983 uscì Mario Bros.

Ma è nel 1985 che Mario, da allora Super Mario, diventa un fenomeno mondiale. Nel quarantesimo anniversario dall’inizio di questo successo planetario, ospitiamo con piacere su We the Italians il Professor Marco Benoît Carbone, che ha scritto uno dei saggi più completi e interessanti su Super Mario: Olive Face, Italian Voice: Constructing Super Mario as an Italian-American (1981–1996)

Prof. Carbone, inizierei chiedendole come nasce il suo interesse nel personaggio di Super Mario

Il primo ricordo che ho di questo personaggio risale a quasi quaranta anni fa, a una festa delle scuole elementari. Ricordo tutti gli occhi puntati su una scatola grigia, che scoprii essere una console della Nintendo, e una litania ossessiva: “giochiamo a Super Mario”. Il fatto di vedere dei personaggi che si potevano muovere liberamente sullo schermo del televisore era affascinante. Poi mi incuriosì il fatto che quel personaggio avesse un nome italiano.

Diversi anni dopo, appresi che i giochi Nintendo provenivano dal Giappone. Mi domandai, quindi, quale fosse la storia di Super Mario: è da questi momenti, credo, che si sviluppò una certa vaga curiosità. Molti anni dopo, nacque un interesse storico per un’icona pop che ha raggiunto la popolarità - e forse, in parte, la rilevanza culturale - di un Donald Duck o di un Mickey Mouse.

Nel suo lavoro lei racconta le tre fasi principali della scrittura del personaggio Super Mario, dall’inizio alla sua evoluzione…

Mi sono limitato a delineare, senza intento schematizzante, alcune fasi nello sviluppo di una proprietà intellettuale longeva e ormai multiforme.

All’inizio degli anni Ottanta, Super Mario è un personaggio mediterraneo molto generico: un italoamericano, per come questa categoria poteva essere percepita dalla prospettiva di un autore giapponese appassionato di fumetti e di cinema: Shigeru Miyamoto. Questo creativo era stato assunto da Nintendo, un’azienda che aveva iniziato producendo carte da gioco, alcune su licenza Walt Disney. Miyamoto intraprende una missione particolare: trasformare i videogiochi di questa azienda, con base a Kyoto, in esperienze che non si risolvano nell’abilità e nel senso di sfida, ma ruotino intorno a delle storie, delle gag e personaggi memorabili.

Miyamoto si cimenta su diversi giochi che si riveleranno rivoluzionari sul piano del design e della presentazione dei personaggi: Donkey Kong, Mario Bros., e poi Super Mario Bros, che produce un impatto commerciale deflagrante.

All’inizio, controlliamo Jumpman. Questi, poi, prende il nome di Mario, forse perché Miyamoto cercava un personaggio non troppo giapponese e non troppo stereotipato, che potesse risultare identificabile e buffo sia in Giappone che negli Stati Uniti, mercato su cui Nintendo puntava fortemente. Riguardo alla scelta dell’Italia, forse Miyamoto aveva visto il Padrino di Francis Ford Coppola, o magari era stato esposto a una certa iconografia tipica dell’italiano migrante e working class con le bretelle e la coppola, che si ritrovava spesso nei film e nei prodotti d’animazione.

Probabilmente c’era anche un discorso culturale che proveniva dal Dopoguerra. Se bisognava puntare su un personaggio simpatico, un po’ stravagante e originale, forse un personaggio italiano avrebbe funzionato. Il Giappone guardava all’Italia come un Occidente di un tipo particolare: l’Italia non era la superpotenza americana o l’ex impero britannico, non era il rivale industriale tedesco o l’orgogliosa Francia. Forse l’Italia era diversa, come sostengono alcuni studiosi come Toshio Miyake: era un ex alleato fallito della Seconda guerra mondiale; ed era un paese percepito come legato a tradizioni folkloriche, alla cucina, all’arte, alle tradizioni, alla famiglia: qualità percepite come positive in Giappone. In ogni caso, la vaghezza del riferimento all’Italia incuriosiva.

In più, come dicevo, gli italiani erano ben noti nella cultura statunitense, il mercato sul quale Nintendo nutriva forti interessi commerciali. Quando, però, Super Mario sbarca negli Stati Uniti, il personaggio ha un successo forse inaspettato anche da Nintendo. Forse perché in quel paese multietnico e di migranti gli italoamericani sono un gruppo assai riconoscibile sul piano demografico, e questo trasforma Mario in un fenomeno pop. Tutti richiedono la licenza del personaggio per mettere il suo volto memorabile su merchandising di ogni tipo: pacchi di pasta, spillette, adesivi, telefoni, detergenti, fumetti, cartoni animati, show televisivi - in questi ultimi, spesso enfatizzando i tratti “etnici” del personaggio. Dal Giappone prendono atto del successo: verso la fine degli anni Ottanta, aggiornano un model sheet di Super Mario (un documento che descrive il personaggio, destinato alla produzione e ai creativi), indicando che si tratta di un italoamericano: per la precisione, di un newyorchese di Brooklyn.

Questo aspetto continuerà a connotare il personaggio fino ad oggi, sebbene nei decenni successivi l’azienda abbia deciso di gestire l’identità di Mario con molta elasticità. In certi giochi, Mario ha di italiano solo il nome. Mario diventa parte di un universo di personaggi simil-disneyano, molto ampio e ramificato, che comprende centinaia di giochi e prodotti. Super Mario è il suo brand dal maggiore successo e il personaggio deve mantenersi sufficientemente tratteggiato da risultare memorabile e al contempo abbastanza vago da essere adattabile di prodotto in prodotto: dal platform game classico in cui si salta di piattaforma in piattaforma al gioco di tennis. Ciononostante, in molte occasioni, l’identità italica si fa più marcata: Mario guida una vespa, pronuncia frasi come ‘mamma mia’ e ‘it’s-a-me, Mario’ (rigorosamente, con la schwa intervocalica del cliché dell’italenglish) e sogna piatti di spaghetti, pici, ravioli e lasagne.

La sua ricerca si concentra in particolare su voce, doppiaggio e accento. Ci dice di più su questo argomento?

Intorno alla metà degli anni Novanta si evolvono i supporti e le tecnologie. Le musiche orchestrali, le voci recitative e i dialoghi registrati iniziano a diventare un potenziale selling point perché rendono i personaggi più vivi e vibranti. Nintendo si cimenta nel dotare Super Mario di una voce e, dopo qualche esperimento portato avanti in alcuni prodotti di nicchia, decide di ufficializzare la voce del personaggio in Super Mario 64.

La voce è quella dell’attore Charles Martinet, che oggi (sebbene sia di recente cambiato il doppiatore) è la voce di Mario ben riconoscibile al pubblico. Charles Martinet è un attore rodato e, quando si tratta di sperimentare il tipo di voce da conferire a Super Mario, parte proprio dall’idea di un accento italico. Nel produrlo, attinge a un repertorio consolidato di tipi (e stereotipi) nazionali che attori e doppiatori impiegavano per i personaggi dei cartoon (e non solo: sin dall’avvento del cinema sonoro, si possono rivenire diversi manuali per attori molto interessanti, colmi di indicazioni stereotipate su come produrre le affettazioni di diverse etnie e nazionalità). Il risultato è un italiano iperreale, che mette a frutto in chiave bonaria e comica alcune caratteristiche percepite come tipicamente italiane dai parlanti anglofoni: il rotacismo, la vocale interconsonantica di it’s-a-me, un certo ritmo.

Qual è la differenza con il Wiseguy English, la cadenza usata da molti personaggi cinematografici italoamericani che consolidano l’immaginario popolare degli italoamericani con accento siciliano e coppola?

Prima di Martinet c’era stata qualche prova, con delle voci maschili e adulte dall’accento tipico di New Jersey o simili, ma Martinet azzecca una combinazione particolare, mescola due tipi di accento. Il primo è quello dell’italiano statunitense di seconda generazione, che si trova, per l’appunto, nel cinema, per esempio nei ganster movie, e che si potrebbe definire come un ethnically accented English di madrelingua. Il secondo è un’inflessione volutamente e scherzosamente sgrammaticata, come quella di un non-madrelingua, conferita in un registro infantile, squillante, come ci si potrebbe aspettare da un personaggio dall’aspetto neotenico e gioioso. Il cocktail è risultato di grande successo, ed è divenuto il canone della Super Mario voice.

Che rapporto c’è tra Super Mario e gli stereotipi e i cliché che da sempre accompagnano gli italoamericani?

Quando Super Mario si trasferisce negli Stati Uniti fioccano diversi prodotti su licenza. Alcuni di questi sono videogiochi e, in questo caso, Nintendo esercita un controllo relativamente forte sulla caratterizzazione dei propri personaggi, perimetrandoli dentro le esigenze di prodotti che puntavano sulla indeterminatezza culturale e sul tono fiabesco e irreale per conquistare persone di ogni angolo del mondo. In altri casi, come le serie televisive prodotte negli Stati Uniti, il fatto che si tratti di produzioni esterne comporta delle caratterizzazioni culturali situate.

Riaffiora quindi qualche vecchio stereotipo, sebbene trasfigurato in una chiave bonaria e inoffensiva. Nella serie televisiva The Super Mario Bros. Super Show (1989) (un misto tra animazione e live action), Mario e Luigi sono gli italiani working class chiassosi, caciaroni e ossessionati dal cibo spesso riscontrati nelle industrie culturali anglofone. In alcune puntate della stessa serie, si notano alcune scene di “turf war” tra fazioni di personaggi cartooneschi in cui Mario e compagnia indossano dei gessati, insieme ad altri riferimenti che rischiano di evocare l’idea del gangster italoamericano, che ha lungamente connotato le narrazioni degli italiani negli Stati Uniti (attirando gli strali di associazioni come la Italian Anti-Defamation League e però anche il controverso e indimenticabile glamour dei film della New Hollywood).

In ogni caso, qualche traccia di stereotipo aveva tracimato nella localizzazione dei giochi: i funghetti malefici che Super Mario spiaccica nei suoi giochi si chiamavano kuribō nella prima versione giapponese; in inglese, diventano i Goombas, da “goombah/coombah”. Questo slang proviene dai linguaggi regionali parlati dalle comunità statunitensi: compare, cumpari, cumpa’. Negli Stati Uniti poteva richiamare sia l’idea di un “amico” sia, ahinoi, quella del “gangster di quartiere”.

Nel suo lavoro lei parla di “oliveface" e "olivevoice". Di che si tratta?

Sono due termini che ho impiegato per discutere come le industrie culturali come quelle del cinema, dei mezzi di informazione e anche del videogioco abbiano codificato i personaggi mediterranei secondo una chiave etnica: in questo caso, quella dell’olive, dell’olivastro. Il volto olivastro è quello dei personaggi mediterranei tipici o stereotipici: melanismo, nasi prominenti, peluria diffusa, caratteri irruenti e altre aspettative e proiezioni culturali. La voce olivastra è quindi, per estensione metaforica, il modo di parlare una lingua seconda con l’accento di un personaggio mediterraneo.

Quando Mario ottiene una voce parlata, Nintendo assolda una persona che non conosce l’italiano e che non è di origini italiche. L’attore, quindi, “performa” la voce da esterno alla cultura. Per farlo, mette in opera delle indicazioni su come debba suonare un italiano in un cartoon o un medium simile. Tali aspettative sono informali, ma anche vere e proprie indicazioni codificate nei manuali di recitazione dell’epoca: un riflesso di come la cultura anglofona percepisse la lingua “straniera” come un qualcosa di minoritario e incapsulabile in una riduzione sintetica. Storicamente, i cliché offrono ad artisti e doppiatori dei formulari “economici”: il personaggio mediterraneo dovrà avere questa faccia olivastra, dovrà sillabare come chi parli l’inglese con l’accento italiano (o greco); magari amerà l’olio d’oliva, la pizza e la pasta (proprio come il nostro vicino, o il nostro amico che gestisce il ristorante italiano; o come il Super Mario della serie televisiva).

Il personaggio oliveface presenterà tratti ben noti, pensati come propri al suo gruppo: positivi o negativi - nonché interiorizzati o rifiutati dagli appartenenti a quel gruppo. Infatti, gli stereotipi sono una potenziale “minaccia” per chi ne venga rappresentato (da cui il termine stereotype threat): stando alla generalizzazione, tutti gli italiani e le italiane dovrebbero essere bruni, dovrebbero parlare in un certo modo, dovrebbero avere un certo carattere, dovrebbero amare la pasta, dovrebbero avere la stessa cultura, la stessa storia. E se così non fosse?

Le industrie culturali e i media sono state sempre al centro di questi processi ormai molto dibattuti: dalla questione della propaganda bellica a quelle contemporanee sulla diversità nel cinema. Per la mia formulazione, sono debitore alla black theory, corrente di ricerca che analizza criticamente il potere delle industrie culturali di creare delle realtà simboliche con forti effetti politici. Le identità nere e indigene hanno per secoli risentito di semplificazioni, caricature e pratiche degradanti come la blackface, che le hanno ridotte a macchiette in narrazioni in cui erano comparse da deridere.

Nel parlare di olive face e olive voice non ho voluto compiere una sovrapposizione esatta tra questa storia di abusi e degradazione e la condizione italica e mediterranea: sono storie diverse, sebbene le identità italiane abbiano navigato in termini storicamente complessi la “bianchezza” dominante negli Stati Uniti. In questo caso, ho voluto solo concentrarmi sui processi rappresentativi, che presentano dei parallelismi: comunicare una identità stilizzata, semplificata.

Super Mario è un idraulico italoamericano di Brooklyn protagonista di videogiochi, film, pubblicità, programmi televisivi: che impatto ha avuto sulla cultura giovanile americana e italoamericana?

Un impatto notevole, perché, come anticipavo, Super Mario è diventato un’icona pop in grado di trascendere il solo ambito dei videogiochi.

Negli Stati Uniti, gli italoamericani sono un gruppo riconoscibile ed amato. Negli anni Ottanta e specialmente nei Novanta l’Italia iniziava anche ad essere riconoscibile globalmente grazie al made in Italy - la moda, il cibo, l’automobilismo, l’arte. Si è parlato di “Italy boom” in molte parti del mondo, durante il quale le persone hanno imparato a celebrare la cucina italiana, la pasta, il vino, la musica lirica: l’italiano è stato a lungo hip e a volte fashionable.

Questo ha sicuramente influito sul successo del personaggio. Tuttavia, come accennavo, una trasformazione nel modo in cui Super Mario e gli altri personaggi navigano l’italianità sta nel fatto che negli ultimi anni - forse un decennio - l’azienda madre giapponese ha assunto un ruolo di controllo molto più attento e pianificato dei propri asset: adesso, i prodotti più disparati presentano elementi figurativi e tematici più omogenei rispetto al passato. Il Super Mario d’animazione delle sale cinematografiche è un’estensione molto coerente dei videogiochi attuali: ha lo stesso viso, abita gli stessi mondi, ed è più o meno lo stesso personaggio. Insomma, forse sarà difficile ritrovarsi un altro film con Bob Hoskins nel ruolo dell’italiano tracagnotto (Super Mario Bros., 1993), che poco c’entrava con i videogiochi cartooneschi dell’epoca, o un altro telefilm in cui Mario e Luigi sono idraulici di mezza età ammiccanti e caciaroni, come negli show televisivi degli anni Ottanta.

A 40 anni di distanza dall’uscita di Super Mario Bros, perché questo personaggio ha avuto un successo così clamoroso, secondo lei?

È sicuramente un insieme di fattori, forse nel complesso di difficile decifrazione o persino imponderabili, sebbene si possa provare a identificarne alcuni.

Di certo Super Mario è sinonimo e garanzia di videogiochi di alta qualità. In alcuni casi questi giochi hanno rappresentato dei punti di svolta nella storia del design. Grazie ad essi l’azienda, in certi periodi storici, è divenuta sinonimo stesso di videogiochi. Questo successo è transgenerazionale: i prodotti di oggi vendono anche la nostalgia di chi vi sia cresciuto, e che magari oggi acquista le nuove versioni anche per le proprie figlie e figli.

Molti giochi che hanno per protagonista Super Mario incarnano una filosofia volta a trasportare chi gioca in una dimensione di spensieratezza. Sono quasi sempre adatti a quasi tutte le età incarnano la capacità storica dell’azienda di armonizzare le diverse capacità del medium videoludico, che è insieme scienza e forma d’arte, entusiasmo per il piacere del controllo e immersione in immagini, suoni e storie. Super Mario incarna una fantasia universale: correre per prati, saltare su piattaforme volanti, librarsi in volo, nuotare. Attività mediate che rispondono forse psicologicamente al moto di energia dell’infanzia, all’oasi felice teorizzata da Eugene Fink, quando rifletteva sulla fondamentale funzione esistenziale della dimensione ludica per gli esseri umani. Il volto di Super Mario, i suoi tratti ormai generalmente neotenici, il temperamento gentile, la caratterizzazione positiva lo hanno reso un personaggio versatile in cui dimenticarsi dei vincoli quotidiani, corporei e legati all’età - Mario è un avatar che soddisfa in modo ecumenico la nostra sindrome di Peter Pan.

Infine, forse una parte del merito potrebbe stare davvero anche nella sua italianità: molti stereotipi positivi dell’Italia ci dipingono come amabili, gioiosi, leali, appassionati, amanti del bello e del buono, simpatici e inoffensivi. Dunque, Super Mario potrebbe non solo risultare esotico e familiare, ma anche evocare qualcuna di queste idee sedimentate sull’Italia - tanto vaghe, romantiche e inesatte quanto desiderabili.