There is a fascination in the concept of Little Italy that still exists today, when many of these Italian neighborhoods are no longer there. Outdated, but only in some cities, the principle of physically limiting an area of the city according to Italian criteria, the concept of being together, making communities and proudly celebrating their origins remains, sometimes more virtually. We the Italians is in part just that, the virtual re-proposition on the web of the principles that held together the Italians who arrived in America during mass emigration.

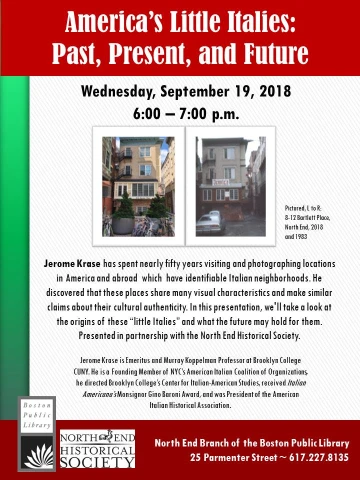

That's why the topic remains very important for us: and we are happy to open our 2019 by talking to one of the most important experts in this field, Professor Jerome Krase, author of "America's Little Italies: Past, Present and Future".

Professor Krase, you spent decades documenting the Little Italies in America. It is a fascinating subject…

Actually Umberto, my research on Little Italies is global in scope. Some of the non-USA examples are in Toronto, Canada, London, Great Britain, and Sidney, Australia. I visited and photographed in most of them and, was very surprised to view a photographic exhibition of “Little Italy” (Kleng Italienesch) at the Luxembourg Embassy in Berlin. Here is a list of my publications on Little Italy and Italian Americans.

How do you define Little Italy?

As to how I define Little Italy, it would take a huge book to describe all the ways that it is done. Historically most definitions have come from the field of demography by which Little Italy is simply a neighborhood in which most residents are able to trace their roots to Italy. Today, on the other hand, the vast majority of places referred to as Little Italies is what I call a touristic “Ethnic Theme Park.” In these extremely popular venues, few, if any, of the local residents are of Italian-descent, but visitors are still attracted to them by their, perhaps mythological, reputation as authentic Italian enclaves. Another large group of people who regularly visit Little Italies to shop and eat are, mostly nostalgic older Italian Americans who seem to be seeking some kind of cultural refreshment. To me they are a puzzle, as they ought to know better.

Although, perhaps not uniquely, I tend to think of “Little Italy” as an idea or as an ideal. In either case, this utopian urban village is a very powerful notion that captures the minds of people seeking a safe and comfortable place in which to live, or a commercial district to shop for Italian fashions and sample delicious food. What Americans call annual “Feasts” and Italians call Feste are the times of year during which local streets are jam-packed with visitors from near and far. There are many other ways by which people learn about Italian neighborhoods. For example, the semi-fictional idea of Little Italy has long captured the attention of Italian, Italian American or other fiction writers and film-makers who have fashioned from their own experience, or more likely their naïve imaginations, an ethnically and visually appropriate location for an organized crime drama like Goodfellas or a romantic comedy like Moonstruck.

In reference to the latter, when I was appointed by Governor Mario Cuomo to membership of the New York State Council for the Humanities in the 1980s, I was asked by a DreamWorks executive on the Council what I thought about Cher’s Italian American accent. I was told that the director of the film had hired a famous writer to work on her accent. To be honest, I told him, her accent was one I seldom heard in the film’s Brooklyn’s Carroll Gardens setting. However, it was one that most viewers would recognize as stereotypically Italian American. In contrast, when I was active in Italian American community organizations, I had met on several occasions a real Italian American Brooklynite actor in the film, Vincent Giardina, whose “normal” voice would not pass as authentically Italian American.

In Movieland, there are many, both positive and negative, models of Little Italy as an ideal ethnic enclave which can be at the same time quietly dark and sinister as well as loud, bright and friendly. What they all have in common is being encased in music such as the 1950’s popular music soundtrack that included Dione and the Belmont’s “I wonder Why” in Chazz Palmentieri’s A Bronx Tale, or the Italian and Italian American inspired soundtracks of Mario Puzo-inspired Godfather trilogy (1972, 1974, 1990). It must be noted that “The Belmonts” got their name from the Belmont Little Italy in which they and Chazz Palmentieri grew up, that was the setting for A Bronx Tale. A personal example of the power of music is when I took my children and grandchildren to Sicily to visit my grandparents’ hometown of Marineo in the Province of Corleone, during which I couldn’t get the theme song from The Godfather (1972), “Speak Softly Love,” out of my head.

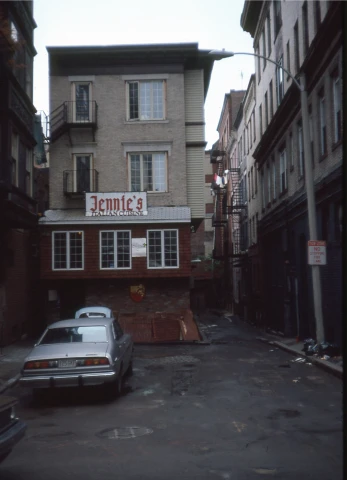

As to essential elements of real and imagined Little Italies, in my writing, and especially in my photography, I have focused on the vernacular or otherwise commonplace landscapes of urban street scenes. Universally required are, mostly “red-sauce,” Italian Restaurants, barber shops, delicatessens (salumerie), both bread and pastry bakeries, pork stores, green-grocers, men of various ages congregating on street corners, signs for social clubs, children playing the streets, and women shopping at local stores. The variety of street-scenes vary depending upon the predominant Italian generation (1st,2nd, 3rd, etc) and the proportion of non-Italian ethnics living in the area. Social class is another important variable, but most stereotypically they are working-class Today “hipsters,” Italian American or not, have become a common feature of historically Italian enclaves in the center of the city that are rapidly gentrifying.

The story of the several Little Italies in America have a few turning points common to almost every one of them. The crowds of a century ago, the transformations of the post-war period, the emptying of Italians in better economic conditions that moved to more comfortable neighborhoods...

In my well-informed opinion, Little Italies are iconic because Italians stayed where they first settled a generation or two longer than the other ethnic groups such as Irish and Eastern European Jews with whom they first shared the neighborhood. What I discovered during the course of my extensive research in Italy, is that Italian culture features an extremely strong connection to place. Most people mention a strong commitment to family as the most powerful force in Italy’s residential culture, but as I found, it is family anchored to a place. The city, town, village or neighborhood is the necessary stage for acting out the culture.

Dense central city neighborhoods are no longer the best venues to search for genuine descendants of Italy. But, places in which most Italian Americans now live, such as unattached single-family suburban homes where the need for Italian provisions is served by large and small shopping centers are not regarded as Little Italies. Examples of those which I have visited and photographed such as Babylon, in Long Island, are towns where the largest ancestry reported on the U.S. Census is Italian. In the case of the town of Babylon, about a third of the total population are Italian American. Some clues to their contribution to the locality are nearby borough of Marconiville and the American Venice development. Marconiville was developed by John Campagnoli for Italian Americans which he named in honor of his close friend, Guglielmo Marconi, inventor of the wireless telegraph. Many streets in this area bear the name of famous Italians. The American Venice development has statues of winged lions on towering columns guarding the entrance to a series of arched Venetian bridges leading to Italian-style villas.

Where are the Little Italies you talk about in your presentation?

Most of my public and academic presentations on “Little Italies: Past, Present, and Future?” include dozens of places. Since I cannot adequately discuss all of them during a single presentation, I show a few examples of each from my photo archives and then focus on one or two Little Italies that are most relevant for those attending my lectures. For example, when I gave a public lecture on Boston’s North End Little Italy at the North End Public Library in Boston, I showed photographs from my visual research there in 1984 and 2018. (I should add that I also gave these lectures in Bari, Naples, Pisa, Rome, and Trento)

I had an interesting experience giving this presentation when I was Director of Italian American Studies at Brooklyn College. Some of my first and second-generation Italian American students asked me to give my “Little Italies” lecture at their parents’ social club in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. My reception was much more respectful than I was used to, and the men were very quiet while I showed photos and spoke about them. The mostly male audience was deadly silent during the presentation. After a whisper of polite applause at the conclusion, one of the men came up to me during the mandatory espresso and pastries, and said “Thanks professore. I thought we were the only people who did these kinds of things.”

What’s the most traditional Little Italy still alive today?

As stereotypical traditional Little Italies require the predominance of Italian residents and businesses, there are very few and when they can be found they are much smaller and are less obvious when embedded within more ethnically and economically diverse local contexts such as the highly gentrified Wooster Street in New Haven, Connecticut and New York City’s Mulberry Street which is almost dissolved by the surrounding expanding Chinatown.

Are there anecdotes, stories, legends about one or more than one Little Italy you’d like to tell our readers? And, does the concept of Little Italy still make sense these days?

The vast majority of Americans today who can trace their roots to Italy have become assimilated. In the third generation there are few easily recognizable vestiges of the culture of their grandparents. Fewer Italians are emigrating to the United States today seeking citizenship or permanent residency. Even when they do, they don’t pour into Little Italies in order to renew or invigorate the local culture. Italian culture has also changed and evolved and in many cases doesn’t “fit” that which has been established before they arrived, but nostalgia and imperfect memory have maintained some basic elements such as those I write about in my “Traces” column.

Commercially-speaking, the concept of Little Italy absolutely still make sense! The simple concept of Little Italy still sells even more so today than in the past when there still was some ethnic authenticity to them. Also, the less you know about the real places in which Italians actually lived “then,” the more inviting the historically sanitized versions of them are “now.” I am always especially amused when I encounter the large numbers of “real” Italians (those legions of tourists from Italy) whom I find excitingly roaming the busy commercial streets of Little Italies such as on Mulberry Street in Manhattan. It appears to me that this popular, rather crude and excessively negative, view fits their preconceived image of their more and less distant cousins in America. These Italian American “Ethnic Theme Parks” appeal to them even more than to non-Italian tourists, or so it seems.

As to a more complicated understanding of Little Italy I must stress that it is also a social and cultural performance that is acted out on various local stages such as on street corners and in commercial establishments. For example, behind the more touristic scenes in Ethnic Theme Parks exists another, more authentic, Little Italy. Last June, I was invited by James Pasto, a professor at Boston University, to give a walking tour and photographic workshop for his students in Boston’s famous North End Little Italy. I had photographed there every few years since the early 1980s and I was exploring with them how the scenes had changed. Professor Pasto had grown up in the neighborhood but was no longer living there. However, he continued to be an important part of the North End’s Italian American social fabric. As we walked through the complex network of streets and visited stores and restaurants, he encountered dozens of old friends. While they met, hugged, kissed, and conversed, the old neighborhood magically appeared in their words and gestures. They also passionately spoke to our students about the “now” of the neighborhood compared out to what it was like “then.”

One incident was especially telling about the North End’s Italianità. When our group passed by an open door, Professor Pasto looked inside and loudly greeted an older woman sitting inside with her children. To her delight, and that of our student-tourists, we were invited to enter and say hello. Shortly thereafter, while we explored a narrow dark alley that opened into a delightful courtyard, another old friend came out of his apartment to see who was invading the space and, seeing Pasto, he welcomed us all into the almost private spaces. This reminded me of my, once more frequent, visits to ordinary neighborhoods in Italy, from Trento to Naples, where it usually took me only two or three days of exchanging respectfully polite greetings with locals, before I become part of the local scene. Of course, speaking reasonable Italian and understanding the etiquette of the street culture made it easier.

Most people I know, Italian American, have a low opinion of Naples. For them “See Naples and Die” is a prediction. When I was in Naples for a week-long ethnography conference held in Mostra d'Oltremare, I stayed with my wife in an upscale hotel near the Castel Nuovo. Every day I had to walk to and from La Stazione Napoli Montesanto for the (often late) train that would take me to the conference. By the third day of passing through the competing scents of freshly baked sfogliatelle and fresh fish in the Quartieri Spagnoli, almost everyone I passed offered me a greeting and a smile.

Is there anything Italy could do today to preserve the Little Italies all over America?

Unfortunately, in my experience with large and small historical organizations, “preservation” means to sanctify and then mummify the most treasured, positive, memories of local Italian American leaders or benefactors and put them on display for visitors. Although it is important to accurately record and preserve in an archive a treasure trove of local memory, this must be done objectively. Most importantly, the choice of what is to be memorialized ought to take into account not only the past but, the neighborhood’s current and future realities. Limiting local museums, cultural centers, high school and grade school curricula, walking tours, or historical markers to laments about the loss of a real or imagined past is of little interest to me. This kind of truncated story of the vast contributions of Italians to American society also tends to reinforce the limited stereotypical views of OUR rich history.

C'è un fascino nel concetto di Little Italy che continua ad esistere ancora oggi che molti di questi quartieri italiani non ci sono più. Superato, ma solo in alcune città, il principio di limitare fisicamente una zona della città secondo i criteri italiani, il concetto di stare insieme, fare comunità e celebrare con orgoglio le proprie origini rimane, a volte più virtualmente. We the Italians è in parte proprio questo, la riproposizione virtuale sul web dei principi che tenevano insieme gli italiani che arrivarono in America durante l'emigrazione di massa.

E' per questo che il tema per noi rimane molto importante: e siamo felici di aprire il nostro 2019 parlandone con uno dei più importanti esperti in questo ambito, il Professor Jerome Krase, autore di "America’s Little Italies: Past, Present and Future"

Professor Krase, lei ha passato decenni a documentare le Little Italies in America. Si tratta di un argomento affascinante...

In realtà Umberto, la mia ricerca sulle Little Italies ha una portata globale. Alcuni degli esempi non statunitensi sono a Toronto, Canada, Londra, Gran Bretagna e Sidney, in Australia. Ho visitato e fotografato la maggior parte di esse e sono rimasto molto sorpreso di vedere una mostra fotografica sulle "Little Italy" (Kleng Italienesch) presso l'Ambasciata del Lussemburgo a Berlino. Qui c’è un elenco delle mie pubblicazioni sulle Little Italies e gli italoamericani.

Come si definisce secondo lei una Little Italy?

Per quanto riguarda la mia definizione di Little Italy, ci vorrebbe un libro enorme. Storicamente la maggior parte delle definizioni provengono dal campo della demografia, per cui una Little Italy è semplicemente un quartiere in cui la maggior parte dei residenti possono rintracciare le proprie radici in Italia. Oggi, d'altra parte, la stragrande maggioranza dei luoghi chiamati “Little Italy” è quello che io chiamo un "parco a tema etnico" turistico. In questi luoghi estremamente popolari, pochi - se non nessuno - dei residenti locali sono di origine italiana, ma i visitatori sono ancora attratti dalla loro, forse mitologica, reputazione di autentiche enclavi italiane. Un altro grande gruppo di persone che visitano regolarmente le Little Italies per fare la spesa e mangiare sono, per lo più, nostalgici e anziani italoamericani che sembrano essere alla ricerca di una sorta di ristoro culturale. Per me sono un rompicapo, perché dovrebbero avere più buon senso.

Tuttavia, io tendo a pensare alla "Little Italy" come un’idea o un luogo ideale. In entrambi i casi, questo utopico villaggio urbano è una nozione molto potente che cattura la mente di chi cerca un luogo sicuro e confortevole in cui vivere, o un quartiere commerciale per fare acquisti alla moda italiana e gustare cibi deliziosi. Quelli che gli americani chiamano annualmente "Feasts" e gli italiani chiamano Feste sono i periodi dell'anno in cui le strade locali sono piene di visitatori provenienti da vicino e da lontano. Ci sono molti altri modi in cui la gente impara a conoscere i quartieri italiani. Ad esempio, l'idea immaginaria di Little Italy ha da tempo catturato l'attenzione di scrittori e cineasti italiani, italoamericani o di altri autori di fiction e registi che hanno creato un luogo etnicamente e visivamente appropriato per un dramma di criminalità organizzata come Goodfellas o per una commedia romantica come Moonstruck.

In riferimento a quest'ultimo, quando sono stato nominato dal governatore Mario Cuomo a far parte del New York State Council for the Humanities negli anni '80, un dirigente della DreamWorks che faceva parte del Consiglio mi chiese cosa ne pensavo dell'accento italoamericano di Cher. Mi fu detto che la regista del film aveva assunto una famosa scrittrice per lavorare sul suo accento. Ad essere onesti, gli dissi, avevo sentito raramente quell’accento nel posto dove era ambientato il film, Carroll Gardens a Brooklyn. Tuttavia, era uno di quelli che la maggior parte degli spettatori avrebbe riconosciuto come italoamericano secondo lo stereotipo comune. Al contrario, quando ero attivo nelle organizzazioni della comunità italoamericana, avevo incontrato in diverse occasioni un vero attore italoamericano di Brooklyn nel film, Vincent Giardina, la cui voce "normale" non sarebbe passata nell’immaginario collettivo come autenticamente italoamericana.

Nel mondo del cinema ci sono molti modelli, sia positivi che negativi, di Little Italy come ideale enclave etnica che può essere allo stesso tempo tranquillamente scura e sinistra, ma anche forte, brillante e amichevole. Ciò che hanno tutti in comune è l'essere descritti musicalmente con una colonna sonora degli anni '50 che includeva pezzi come I wonder why di Dione and the Belmont’s in A Bronx Tale di Chazz Palmentieri, o con canzoni di ispirazione italiana e italoamericana della trilogia del Padrino di Mario Puzo (1972, 1974, 1990). Va notato che i "Belmonts” hanno preso il loro nome dalla Little Italy della zona di Belmont nel Bronx, in cui sono cresciuti loro e anche Chazz Palmentieri, che è stata l'ambientazione di A Bronx Tale. Un esempio personale del potere della musica è quando ho portato i miei figli e nipoti in Sicilia per visitare la città natale dei miei nonni, Marineo, nella zona di Corleone, durante la quale non sono riuscito a far uscire dalla mia testa la canzone de Il padrino (1972), Speak Softly Love.

Per quanto riguarda gli elementi essenziali delle Little Italies reali e immaginarie, nella mia scrittura, e soprattutto nella mia fotografia, mi sono concentrato sui paesaggi vernacolari o comunque comuni delle scene urbane di strada. Le zone più universalmente richieste sono per lo più ristoranti italiani, barbieri, salumerie, panifici e pasticcerie, macellerie, fruttivendoli, uomini di varie età che si riuniscono agli angoli delle strade, insegne per i club, bambini che giocano per strada e donne che fanno la spesa nei negozi locali. La varietà delle scene di strada varia a seconda della generazione italiana predominante (prima, seconda, terza eccetera) e della proporzione di persone di origine non italiana che vivono nella zona. La classe sociale è un'altra variabile importante, ma la maggior parte degli stereotipi riguarda la classe operaia. Oggi gli "hipster", italoamericani e non, sono diventati una caratteristica comune delle enclavi storicamente italiane nel centro della città, che si stanno rapidamente riqualificando e trasformando.

La storia delle varie Little Italies in America ha alcune svolte comuni a quasi tutte. Le folle di un secolo fa, le trasformazioni del dopoguerra, lo svuotamento degli italiani in migliori condizioni economiche che si sono spostati in quartieri più confortevoli...

Secondo la mia ben informata opinione, le Little Italies sono iconiche perché gli italiani sono rimasti dove si sono stabiliti per la prima volta una o due generazioni più a lungo degli altri gruppi etnici come gli ebrei irlandesi e dell'Est Europa, con i quali hanno condiviso il quartiere. Quello che ho scoperto nel corso della mia vasta ricerca in Italia, è che la cultura italiana ha un legame estremamente forte con il luogo. La maggior parte delle persone parla di un forte impegno verso la famiglia come la forza più potente nella cultura residenziale italiana, ma, come ho scoperto, si tratta di una famiglia ancorata a un luogo. La città, il paese, il villaggio o il quartiere è il palcoscenico necessario per questa cultura.

I densi quartieri centrali della città non sono più i luoghi migliori per cercare i veri discendenti dell'Italia. E i luoghi in cui vive la maggior parte degli italoamericani, come le ville unifamiliari, dove il bisogno di provviste italiane è servito da grandi e piccoli centri commerciali, non sono considerati Little Italies. Esempi di quelli che ho visitato e fotografato, come Babylon, a Long Island, sono città dove il più grande gruppo etnico riportato sul censimento degli Stati Uniti è quello italiano. Nel caso della città di Babylon, circa un terzo della popolazione totale è italoamericana. Alcuni indizi del loro contributo alla località sono il vicino quartiere di Marconiville e lo sviluppo della Venezia americana. Marconiville è stato sviluppato per gli italoamericani da John Campagnoli, che lo ha chiamato così in onore del suo caro amico, Guglielmo Marconi, inventore del telegrafo senza fili. Molte strade di questa zona portano il nome di famosi italiani. Lo sviluppo della Venezia americana invece vede statue di leoni alari su colonne imponenti che proteggono l'ingresso di una serie di ponti veneziani ad arco che conducono alle ville all'italiana.

Dove sono le Little Italies di cui parla nella sua presentazione?

La maggior parte delle mie presentazioni pubbliche e accademiche "America’s Little Italies: Past, Present and Future" comprende decine di luoghi. Dato che non posso discuterli tutti in modo adeguato durante una singola presentazione, mostro alcuni esempi di ognuno dei miei archivi fotografici e poi mi concentro su una o due Little Italies che sono più rilevanti per coloro che frequentano le mie lezioni. Per esempio, quando ho tenuto una conferenza pubblica sul North End, la Little Italy di Boston, presso la North End Public Library a Boston, ho mostrato le fotografie delle mie ricerche visive nel 1984 e nel 2018 (devo aggiungere che ho tenuto queste lezioni anche a Bari, Napoli, Pisa, Pisa, Roma e Trento).

Ho avuto un'esperienza interessante sviluppando questa presentazione quando ero direttore degli studi italoamericani al Brooklyn College. Alcuni dei miei studenti italo americani di prima e seconda generazione mi chiesero di tenere la mia conferenza "Little Italies" al social club dei loro genitori a Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. L’accoglienza fu molto più rispettosa di quanto fossi abituato, e gli uomini erano molto silenziosi mentre io mostravo le foto e parlavo di loro. Il pubblico, per lo più maschile, era decisamente quieto durante la presentazione. Dopo un sussurro di cortesi applausi alla conclusione, uno degli uomini si avvicinò a me durante il rinfresco a base di espresso e pasticcini, e mi disse "Grazie professore. Pensavo che fossimo gli unici a fare questo tipo di cose".

Qual è la più tradizionale Little Italy ancora oggi in vita?

Poiché le tradizionali stereotipate Little Italies richiedono la predominanza di residenti e negozi italiani, ce ne sono pochissime e quando si possono trovare sono molto più piccole e meno evidenti se inserite in contesti locali più etnicamente ed economicamente diversificati, come Wooster Street a New Haven, Connecticut e Mulberry Street a New York City, che è quasi scomparsa per l'espansione della Chinatown adiacente.

Ci sono aneddoti, storie, leggende su una o più Little Italy che vorrebbe raccontare ai nostri lettori? E il concetto di Little Italy ha ancora senso al giorno d'oggi?

Oggi la stragrande maggioranza degli americani che possono far risalire le proprie radici all'Italia è ormai assimilata. Nella terza generazione ci sono poche vestigia facilmente riconoscibili della cultura dei loro nonni. Meno italiani emigrano negli Stati Uniti oggi in cerca di cittadinanza o residenza permanente. Anche quando lo fanno, non si riversano nelle Little Italies per rinnovare o rinvigorire la cultura locale. Anche la cultura italiana è cambiata e si è evoluta e in molti casi non "si adatta" a ciò che è stato stabilito prima del loro arrivo, ma la nostalgia e la memoria imperfetta hanno mantenuto alcuni elementi fondamentali come quelli di cui scrivo nella mia rubrica "Traces".

Dal punto di vista commerciale, il concetto di Little Italy ha ancora senso! Il semplice concetto di Little Italy vende ancora oggi più di quanto non facesse in passato, quando c'era ancora un po' di autenticità etnica. Inoltre, meno si conoscono i luoghi reali in cui gli italiani vivevano "allora", più invitanti sono "ora" le loro versioni storicamente ripulite. Mi diverto sempre di più quando incontro un gran numero di "veri" italiani (quelle legioni di turisti provenienti dall'Italia) che trovano eccitante vagare per le trafficate vie commerciali delle Little Italies, come a Mulberry Street a Manhattan. Mi sembra che questa visione popolare, piuttosto rozza ed eccessivamente negativa, si adatti alla loro immagine preconcetta dei loro cugini più e meno lontani in America. Questi "parchi tematici etnici" italoamericani li attraggono ancora di più di quanto non accada ai turisti non italiani, o almeno così sembra.

Per quanto riguarda una più complicata comprensione del concetto di Little Italy, devo sottolineare che si tratta anche di una performance sociale e culturale che si svolge su vari palcoscenici locali come agli angoli delle strade e negli esercizi commerciali. Per esempio, dietro le scene più turistiche dei parchi tematici etnici esiste un'altra, più autentica, Little Italy. Lo scorso giugno sono stato invitato da James Pasto, professore alla Boston University, a fare un tour a piedi e un workshop fotografico per i suoi studenti nel famoso North End, la Little Italy di Boston. Avevo scattato fotografie lì ogni paio d'anni dai primi anni '80 e stavo esplorando con loro come le scene erano cambiate. Il professor Pasto era cresciuto nel quartiere, ma non vi abitava più. Tuttavia, ha continuato ad essere una parte importante del tessuto sociale italoamericano del North End. Mentre camminavamo attraverso la complessa rete di strade e visitavamo negozi e ristoranti, incontrò decine di vecchi amici. Mentre si incontravano, abbracciavano, baciavano e conversavano, il vecchio quartiere appariva magicamente nelle loro parole e nei loro gesti. Parlavano con passione ai nostri studenti anche del quartiere di oggi rispetto a come era ieri.

Un accadimento disse molto a proposito dell'italianità del North End. Quando il nostro gruppo passò da una porta aperta, il professor Pasto guardò dentro e salutò ad alta voce una donna più anziana seduta dentro con i suoi figli. Per la sua gioia, e quella dei nostri studenti-turisti, ci invitarono a entrare e a salutare. Poco dopo, mentre esploravamo uno stretto vicolo buio che si apriva in un delizioso cortile, un altro vecchio amico uscì dal suo appartamento per vedere chi stesse passando e, vedendo Pasto, ci accolse tutti nei suoi spazi. Questo mi ricordò le mie visite, ancora una volta frequenti, nei quartieri delle città d'Italia, da Trento a Napoli, dove di solito dopo solo due o tre giorni di gentili saluti reciproci con la gente del posto, ero entrato a far parte della scena locale. Naturalmente, parlare un italiano ragionevole e comprendere le usanze della cultura di strada ha reso tutto più facile.

La maggior parte delle persone italoamericane che conosco, hanno una bassa opinione di Napoli. Per loro "Vedere Napoli e poi morire" è una previsione. Quando ero a Napoli per una conferenza etnografica di una settimana alla Mostra d'Oltremare, soggiornavo con mia moglie in un hotel di lusso vicino a Castel Nuovo. Ogni giorno dovevo camminare da e perla stazione di Napoli Montesanto per il treno (spesso in ritardo) che mi portava alla conferenza. Al terzo giorno di passaggio tra i profumi contrastanti delle sfogliatelle appena sfornate e del pesce fresco dei Quartieri Spagnoli, quasi tutti coloro che incontravo mi salutavano e mi sorridevano.

C'è qualcosa che l'Italia potrebbe fare oggi per preservare le Little Italies in tutta l'America?

Purtroppo, nella mia esperienza con grandi e piccole organizzazioni storiche, "conservare" significa santificare e poi mummificare i ricordi più preziosi e positivi dei leader o benefattori locali italoamericani e metterli in mostra per i visitatori. Anche se è importante registrare accuratamente e conservare in un archivio un tesoro di memoria locale, questo deve essere fatto obiettivamente. Soprattutto, la scelta di ciò che deve essere commemorato deve tener conto non solo del passato, ma anche delle realtà presenti e future del quartiere. Limitare i musei locali, i centri culturali, i programmi delle scuole superiori e delle scuole elementari, le escursioni a piedi, o gli indicatori storici alla semplice lamentela della perdita di un passato reale o immaginario è per me di scarso interesse. Questo limitato tipo di storia del vasto contributo degli italiani alla società americana tende anche a rafforzare le visioni stereotipate della nostra ricca storia.