What unites all the people I have had the good luck to interview is their relationship with an aspect of the marriage between Italy and America. Everyone experiences it from a different point of view, on this or that side of the ocean, and for We the Italians it is nice to meet people who are different in culture, sex, age, experience, tastes and values, with this common thread that links them to each other and to us.

Sometimes I have the pleasure of personally knowing the interviewee in person, as in this case, which is special to me. I met Paolo Battaglia a few years ago: he has the rare gift of combining curiosity and talent, humility and charisma, generosity and success. I have learned a lot from him about content and method, stubbornness and sacrifice, farsightedness and research. Allow me to have the special pleasure of welcoming and thanking him, here on We the Italians

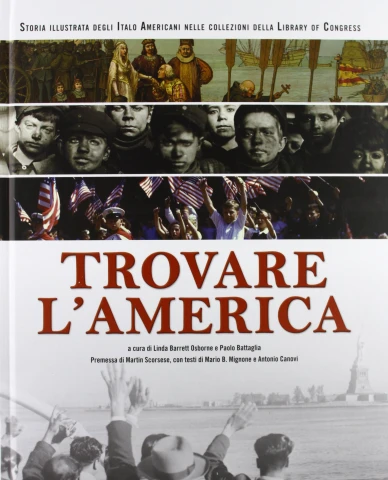

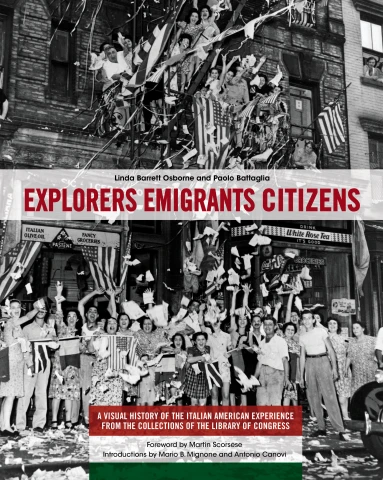

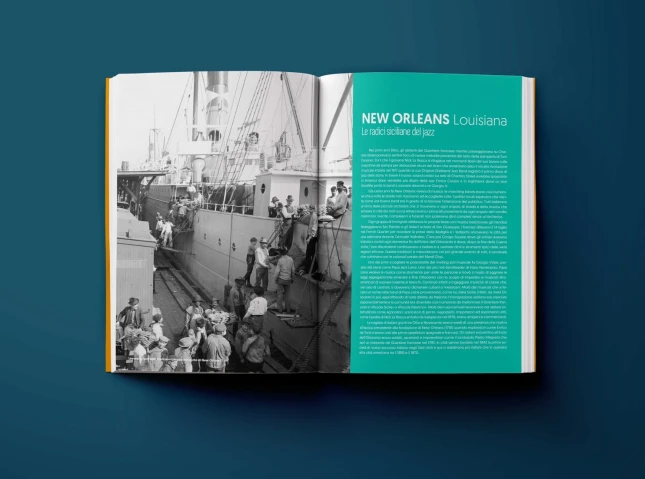

Paolo, we met a few years ago, when you completed a historic and beautiful undertaking, culminating with the publication of the beautiful book "Explorers Emigrants Citizens: A Visual History of the Italian American Experience", also in the Italian edition entitled "Trovare l’America". It is a milestone in the literature that tells the story of the Italian experience in the United States. Can you tell us how it was born and what the contents are?

“Explorers Emigrants Citizens” was one of those adventures that really makes you think that the USA still has something more to offer to those who have dreams. My dream as an Italian micro-publisher specializing in photographic books was to publish an illustrated story about the Italian presence in America. To make it a reality, I tried to aim high: I wrote to the Library of Congress in Washington proposing a joint research on everything Italian American they had in their endless collections. The surprising thing for those of us who are used to navigating between contacts and recommendations is that after a few weeks the offices of the Library of Congress answered me saying they were interested in my project.

After two years of work with their researchers, in autumn 2013 “Explorers Emigrants Citizens” was published, enriched by the contribution of Martin Scorsese who wrote the preface.

The book tells, with more than 500 images, the parable of Italians in America addressing, three major issues. It opens with "Explorers" that examines the first centuries of European colonization when the few Italians who arrived were travelers, soldiers of fortune, missionaries and fortune seekers. These are sometimes names that have entered history books such as Giovanni da Verrazzano, the first European to enter New York Bay, and sometimes lesser-known personalities such as Carlo Gentile, one of the first photographers to portray the natives of the Southwest.

Then we continue with the most consistent chapter entitled "Emigrants", which traces the decades in which hundreds of thousands of Italians arrived every year at Ellis Island; decades in which our countrymen in America had to fight against discrimination and, in some cases, the open racism of Americans, and in which the foundations of the Italian American culture were forged.

The book closes with the chapter "Citizens" which deals with the epoch-making passage in which the children and grandchildren of emigrants are fully integrated into American culture and society, becoming fundamental protagonists of American development in every field, from politics to culture and sport.

In this book you collaborated with Mario Mignone: a wonderful Italian American, a professor with a big heart, an Italian so proud of his roots, who unfortunately left us a few months ago. We ask you for a memory of Mario, whom many readers of We the Italians have known and appreciated

One of the most important legacies of the work done to achieve “Explorers Emigrants Citizens” is the extraordinary people I met during my research. Mario was certainly the person who, together with the co-author of the book, Linda Barrett Osborne - 100% Italian American in spite of her name - I felt closest to in these years.

His great experience, passion and sensitivity almost naturally led me to ask for his advice when I wanted to undertake some new project. And while he was always very committed to the activities of the Center for Italian Studies in Stony Brook, he was always available to offer advice and encouragement. Also last year, before facing the coast to coast that allowed me to conclude the project "Italian American Country", I had been his guest for a couple of days and, discussing with him, I was able to focus on some important aspects of this new work of mine.

We were supposed to meet last October at the end of my American presentation tour, but unfortunately the news of his sudden death reached me in California. I feel that I have lost not only a teacher, but also and above all, a good friend.

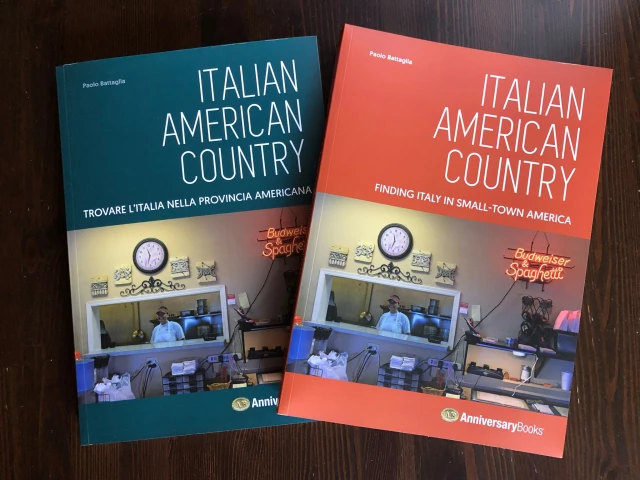

Your new work is called "Italian American Country" and it's both a book and a documentary (here the trailer in English, here the one in Italian). In my opinion it's another masterpiece, and it tells stories of Italians in the American regions, far from the big cities...

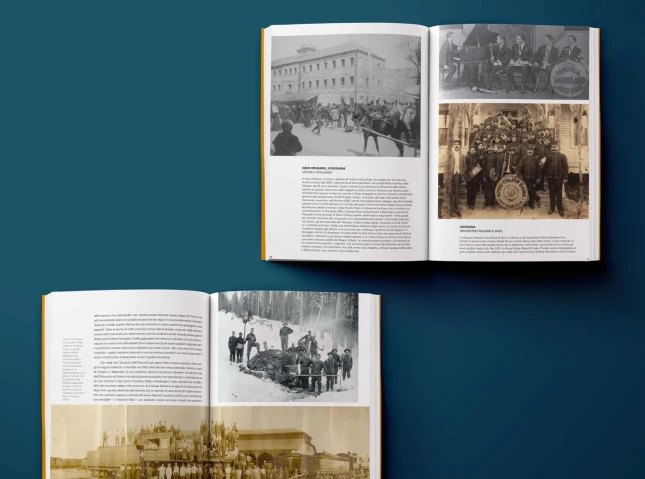

Thank you for calling it a masterpiece. I don't know if it is. But I'm sure it's a unique work, at least for the past century. It had been since 1905, when Italian Ambassador Edmondo Mayor Des Planches crossed the United States to visit the most isolated Italian communities since anyone bothered to see what it means and what it has meant to be Italian far from the great cities of the Northeast.

A fundamental part of this project was the journey: replacing the rails on which the ambassador's private carriage was travelling with the asphalt of the highways, I travelled for over 15,000 miles, meeting and interviewing over one hundred people and visiting dozens of places that have - or have had - a role in the history of Italian emigration. From Barre in Vermont, where the stonemasons from Carrara brought their art and their political ideas, to Pittsburg in California, where the Latin sails of the fishermen from Isola delle Femmine conquered rivers and oceans. From Valdese, founded by Piedmontese Protestants who moved their community from the Alps to the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, to Denver, which is now a large city, but that in the late nineteenth century when the Italians began to arrive was still a frontier outpost. Another goal that I hope to have achieved with this work, especially with the documentary, is to finally give voice to the descendants of those who, for various reasons, instead of stopping in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty, arrived in Paradise Valley, in the middle of the Nevada desert, or founded Tontitown, in Arkansas, after escaping the semi-slavery of the Sunnyside plantation.

A few days ago I received a beautiful compliment: somebody told me that they appreciated the documentary because it was not made to support a thesis. And that's right: the documentary was made to listen, not very fashionable today, I know, but certainly useful to try to understand experiences different from ours. To listen to the voices, the testimonies, the memories of those who are Italian in an America far from the big cities.

You have presented your new book and your documentary in different rural areas of the United States. What difference have you found, if there is one, between the Italians there and those in the cities where you presented your first book?

I believe that the substantial isolation from the rest of the Italians in America in which the communities in rural areas have lived has made them somehow more tied to the memory of Italy and its traditions than to the Italian American culture that has developed in the big cities. And it is perhaps for this reason that the welcome they have given me has always been extraordinary.

As I write in the afterword, I was struck by the “joy with which they had shared their stories with a perfect stranger, just because he had arrived with the promise that for once those stories could also be heard in the Old Country. There had been laughter and tears; there was humor, sadness, pride, but above all the desire to share with someone to whom they felt a natural connection for an innate sense of common Italianism that I discovered thanks to them.”

Can you tell us a couple of curious anecdotes you discovered during your new adventure?

In every place I have visited I have met people and events worth remembering here, but if I have to choose some, I will limit myself to those who have made me feel that the Italians have also been part of the history of the American border.

I continue to suffer that childish fascination born many years ago reading books and comics or watching movies about the epic of the Wild West, and therefore could not leave me indifferent to being in Paradise Valley, Nevada (a town that, according to its inhabitants, is still "at the end of the world") and finding myself interviewing Kevin Pasquale, who presented himself with the clothing and stage presence of John Wayne and, looking at the horizon, listed the ranches owned by families descended from Piedmontese emigrants like him.

Or the story told by the volunteers of the Tontitown Historical Museum in Arkansas, where the men who arrived in those remote places from Emilia Romagna, Veneto and Marche had been forced to face outlaws disguised as Indians, who had burned the first church of the Italian community.

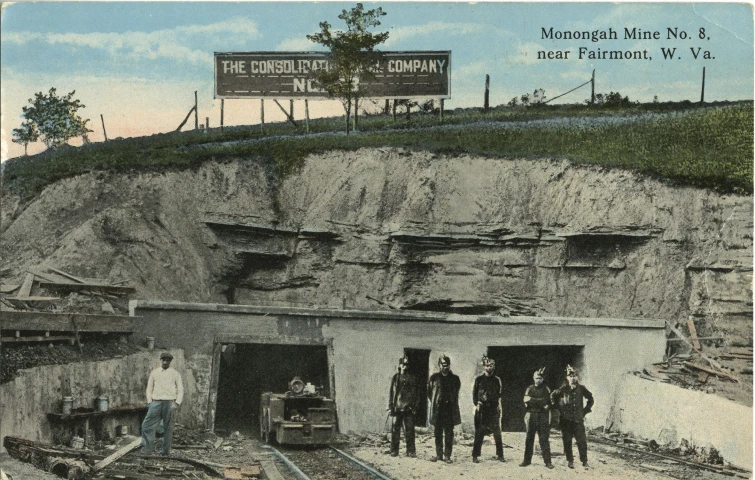

Or finally, the arrival after twelve miles traveled on dirt roads - and a hundred and twenty on almost completely deserted roads - in the ghost town of Dawson, New Mexico, where the only company is that of rattlesnakes of which you are warned by a sign, and the only noise is the creaking of the gate of the cemetery where more than 100 Italian miners are buried, who died at the beginning of the twentieth century when the city was one of the most flourishing mining centers in the region.

In Italy we have a saying: "Non c’è due senza tre” (There is not two without three). Is there a third job about the Italian Americans in your future? We really hope so...

Obviously I would like to continue to tell other stories of Italians in America and I always find new clues and new tracks that should be followed. But as you can imagine, they are projects that are difficult to sustain for a micro-publisher like me, so a lot will depend on the results that we will be able to achieve with "Italian American Country".

On the other hand, I have already started another project, much lighter in its contents, which puts the American culture in contact with the Italian one. It's called "Foodball High" and it's inspired by my passion for American football: last September, I brought to San Diego a group of four young Italian football players - three of them also wore the blue shirt of the Italian team at the European Championships - with their coach who is also a cook in everyday life. Our goal was to start a sort of "cultural barter", football for food, between our boys and the student players of a high school. On the one hand the Italian boys would participate in the training of the football team, experiencing what it means to practice that sport in its homeland; on the other hand they would teach their American teammates to cook typical Italian recipes.

A project that, as you can see, is very different from the previous ones but that, beyond the recreational-sports aspect, has allowed us to reflect on how much our food culture, not only of what we eat but also of how we eat it and how we prepare it, is an aspect that always identifies us. If all goes well (fingers crossed) "Foodball High" should see the light as a documentary by mid 2020.

Quello che accomuna tutte le persone che ho avuto la fortuna di intervistare è il loro rapporto con un aspetto del connubio Italia/America. Ognuno lo vive da un punto di vista diverso, di qua o di là dell'oceano, e per We the Italians è bello incontrare persone diverse per cultura, sesso, età, esperienza, gusti e valori, con questo fil rouge che li lega tra di loro e a noi.

A volte ho il piacere di conoscere di persona l'intervistato, come in questo caso, che è speciale per me. Ho conosciuto Paolo Battaglia qualche anno fa: ha il raro dono di unire curiosità e talento, umiltà e carisma, generosità e successo. Ho imparato tanto da lui sui contenuti e sul metodo, sulla caparbietà e sul sacrificio, sulla lungimiranza e sulla ricerca. Concedetemi di avere un piacere particolare nell'accoglierlo e ringraziarlo, qui su We the Italians

Paolo, ci siamo conosciuti qualche anno fa, quando hai portato a termine un’impresa storica e bellissima, culminata con la pubblicazione del bellissimo volume Libro “Explorers Emigrants Citizens: A Visual History of the Italian American Experience”, anche nell’edizione italiana intitolata “Trovare l’America”. E’ una pietra miliare della letteratura che racconta l’esperienza italiana negli Stati Uniti. Ci racconti come nacque e quali sono i contenuti?

“Trovare l'America” è stata una di quelle avventure che ti fa davvero pensare che gli USA abbiano ancora qualcosa in più da offrire a chi ha dei sogni. Il mio sogno da micro-editore italiano specializzato in libri fotografici era quello di pubblicare una storia illustrata sulla presenza italiana in America. Per realizzarla ho provato a puntare in alto: ho scritto alla Library of Congress di Washington proponendo loro una ricerca congiunta su tutto quello che di italo-americano avevano nelle loro sterminate collezioni. La cosa sorprendente per chi come noi è abituato a navigare tra conoscenze e raccomandazioni è che dopo poche settimane gli uffici della Library of Congress mi hanno risposto dicendosi interessati al mio progetto.

Al termine di due anni di lavoro svolto insieme ai loro ricercatori, nell'autunno 2013 è uscito “Trovare l'America”, impreziosito dal contributo di Martin Scorsese che ha scritto la prefazione.

Il libro racconta con più di 500 immagini la parabola degli italiani in America affrontando tre grandi temi. Si apre con “Esploratori” che esamina i primi secoli della colonizzazione europea quando i pochi italiani che arrivavano erano viaggiatori, soldati di ventura, missionari e cercatori di fortuna. Si tratta a volte di nomi entrati nei libri di storia come Giovanni da Verrazzano, primo europeo a entrare nella baia di New York, a volte di personaggi meno noti come Carlo Gentile, uno dei primi fotografi a ritrarre i nativi del Sud-Ovest.

Si prosegue poi con il capitolo più consistente intitolato “Emigranti” che ripercorre i decenni in cui centinaia di migliaia di italiani arrivavano ogni anno a Ellis Island; decenni in cui i nostri connazionali in America dovevano lottare contro la discriminazione e, in alcuni casi, l'aperto razzismo degli americani e in cui si forgiarono le basi della cultura italo-americana.

Il libro si chiude con il capitolo “Cittadini” che affronta il passaggio epocale in cui i figli e i nipoti degli emigranti si integrano pienamente nella cultura e nella società americana, diventando protagonisti fondamentali dello sviluppo statunitense in ogni campo, dalla politica, alla cultura e allo sport.

Il libro ti vide collaborare con Mario Mignone,: un meraviglioso italoamericano, un professore dal cuore grande, un italiano tanto orgoglioso di esserlo, che purtroppo ci ha lasciato qualche mese fa. Ti chiediamo un ricordo di Mario, che tanti lettori di We the Italians hanno conosciuto e apprezzato

Una delle eredità più importanti del lavoro svolto per realizzare “Trovare l'America” è rappresentato dalle persone straordinarie che ho conosciuto durante la mia ricerca. Mario è stato senz'altro la persona che, insieme alla coautrice del libro, Linda Barrett Osborne – al 100% italoamericana a dispetto del nome – ho sentito più vicino in questi anni.

La sua grande esperienza, la sua passione e la sua sensibilità mi portavano quasi naturalmente a chiedere i suoi consigli quando volevo intraprendere qualche nuovo progetto. E lui, pur essendo sempre impegnatissimo nelle attività del Center for Italian Studies di Stony Brook, si dimostrava ogni volta disponibile a offrire pareri e incoraggiamenti. Anche lo scorso anno, prima di affrontare il coast to coast che mi ha permesso di concludere il progetto “Italian American Country” ero stato un paio di giorni suo ospite e confrontandomi con lui ero riuscito a focalizzare alcuni aspetti importanti di questo mio nuovo lavoro.

Ci saremmo dovuti incontrare lo scorso ottobre al termine del mio tour di presentazione americano, ma purtroppo la notizia della sua improvvisa scomparsa mi ha raggiunto in California. Sento di avere perso non solo un maestro ma anche e soprattutto un buon amico.

Il tuo nuovo lavoro si chiama “Italian American Country” è insieme un libro e un documentario (qui il trailer in italiano, qui quello in inglese). A mio avviso è un altro capolavoro, e racconta storie di italiani nella provincia americana, lontano dalle grandi città…

Ti ringrazio per averlo definito un capolavoro. Non so se lo sia. Sono certo però che sia un lavoro unico, almeno da un secolo a questa parte. Era appunto dal 1905, quando l'ambasciatore italiano Edmondo Mayor Des Planches attraversò tutti gli Stati Uniti per visitare le comunità italiane più isolate che nessuno si prendeva la briga di vedere cosa significa e cosa ha significato essere italiani lontani dalle grandi città del Nord-Est.

Una parte fondamentale di questo progetto è stato proprio il viaggio: sostituite le rotaie su cui viaggiava la carrozza riservata dell’ambasciatore con l’asfalto delle highways, ho percorso 25.000 chilometri incontrando e intervistando oltre cento persone e visitando decine di luoghi che hanno – o hanno avuto – un ruolo nella storia dell’emigrazione italiana, da Barre in Vermont dove gli scalpellini carraresi hanno portato la loro arte e le loro idee politiche, a Pittsburg in California dove le vele latine dei pescatori di Isola delle Femmine hanno colonizzato fiumi e oceani; da Valdese, fondata da protestanti piemontesi che hanno trasferito la loro comunità dalle Alpi alle Blue Ridge Mountains del North Carolina, a Denver, che oggi è una grande città, ma che a fine Ottocento quando iniziarono ad arrivare gli italiani era ancora un avamposto di frontiera. Un altro obiettivo che spero di avere raggiunto con questo lavoro, soprattutto con il documentario, è quello di dare finalmente voce ai discendenti di chi per le ragioni più varie, invece di fermarsi all'ombra della Statua della Libertà, è arrivato fino a Paradise Valley, nel mezzo del deserto del Nevada, oppure ha fondato Tontitown, in Arkansas, dopo essere sfuggito alla semi-schiavitù della piantagione di Sunnyside.

Qualche giorno fa ho ricevuto un bellissimo complimento: mi hanno detto di avere apprezzato il documentario perché non è stato realizzato per sostenere una tesi. Ed è proprio così: il documentario è stato fatto per ascoltare, un atto poco di moda oggi, lo so, ma senz'altro utile per tentare di capire esperienze diverse dalla nostra. Per ascoltare le voci, le testimonianze, i ricordi di chi è italiano in un'America lontana dalle grandi città.

Hai presentato libro e documentario in diverse zone rurali degli Stati Uniti. Che differenza hai trovato, se ce n’è una, tra gli italiani di lì e quelli delle città dove avevi presentato il primo libro?

Credo che il sostanziale isolamento dal resto degli italiani in America in cui sono vissute le comunità nelle zone rurali le abbia rese in qualche modo più legate al ricordo dell'Italia e delle sue tradizioni che non alla cultura italo-americana che si è sviluppata nelle grandi città. Ed è forse per questo che l'accoglienza che mi hanno riservato è stata sempre straordinaria.

Come scrivo nella postfazione, sono rimasto colpito dalla “gioia con cui avevano condiviso le loro storie con un perfetto sconosciuto, solo perché era arrivato con la promessa che per una volta quelle storie potevano essere ascoltate anche nella Old Country. C’erano state risate e lacrime, c’era umorismo, tristezza, orgoglio, ma soprattutto la voglia di condividere con qualcuno verso cui sentivano una connessione naturale per un senso innato di comune italianità che ho scoperto grazie a loro”.

Ci racconti un paio di aneddoti curiosi che hai scoperto durante questa tua nuova avventura?

In ogni luogo che ho visitato ho incontrato persone e vicende che varrebbe la pena ricordare qui ma se devo sceglierne alcuni, mi limito a quelli che mi hanno fatto sentire che anche gli italiani sono stati parte della storia della frontiera americana.

Continuo a subire quella infantile fascinazione nata molti anni fa leggendo libri e fumetti o vedendo film sull'epopea del Wild West e quindi non poteva lasciarmi indifferente essere a Paradise Valley, in Nevada, un paese che a detta dei suoi abitanti è ancora oggi “alla fine del mondo”, e trovarmi a intervistare Kevin Pasquale, che si presentava con l'abbigliamento e la presenza scenica di John Wayne e, scrutando l'orizzonte, elencava i ranch di proprietà di famiglie discendenti da emigranti piemontesi come lui.

O la storia che raccontano i volontari del Tontitown Historical Museum, in Arkansas dove gli uomini arrivati in quei luoghi sperduti dall'Emilia, dal Veneto e dalle Marche erano stati costretti ad affrontare dei fuorilegge travestiti da indiani che avevano bruciato la prima chiesa della comunità italiana.

O, infine, l'arrivo dopo venti chilometri percorsi su strade sterrate – e duecento su strade quasi completamente deserte – nella città fantasma di Dawson, in New Mexico, dove l'unica compagnia è quella dei serpenti a sonagli da cui ti mette in guardia l'apposito cartello e l'unico rumore è il cigolio del cancello del cimitero in cui sono sepolti più di 100 minatori italiani morti all'inizio del Novecento quando la città era uno dei più fiorenti centri minerari della regione.

In Italia abbiamo un detto: “Non c’è due senza tre”. C’è un terzo lavoro che riguarda gli italoamericani nel tuo futuro? Noi speriamo davvero di sì…

Ovviamente mi piacerebbe continuare a raccontare altre storie di italiani in America e ogni volta si trovano nuovi indizi e nuove tracce che andrebbero seguite. Però come potrai immaginare sono progetti che hanno costi difficili da sostenere per un micro-editore come me, quindi molto dipenderà dai risultati che riusciremo ad ottenere con “Italian American Country”.

In compenso, ho già avviato un altro progetto, molto più leggero nei suoi contenuti, che mette in contatto la cultura americana con quella italiana. Si tratta di “Foodball High” e prende spunto dalla mia passione per il football americano: lo scorso settembre, ho portato a San Diego un gruppo di quattro giovani giocatori italiani di football – tre di loro hanno anche vestito la maglia azzurra agli Europei di categoria – con il loro coach che nella vita di tutti i giorni è anche cuoco. Il nostro obiettivo era quello di avviare una sorta di “baratto culturale”, football in cambio di cibo, tra i nostri ragazzi e gli studenti-giocatori di una high school. Da una parte i ragazzi italiani avrebbero partecipato agli allenamenti della squadra di football, toccando con mano cosa significa praticare quello sport nella sua patria; dall'altra avrebbero insegnato ai loro compagni di squadra americani a cucinare ricette tipicamente italiane.

Un progetto che come vedi è molto diverso dai precedenti ma che al di là dell'aspetto ludico-sportivo, ci ha permesso di riflettere su quanto la nostra cultura del cibo, non solo di cosa mangiamo ma anche di come lo mangiamo e di come lo prepariamo, sia un aspetto che ci identifica sempre e comunque. Se tutto va bene (incrociamo le dita) “Foodball High" dovrebbe vedere la luce come documentario entro la metà del 2020.