Anyone who knows the history of Italian emigration in America says that the percentage of Abruzzesi who emigrated to the United States is far greater than the size of its territory and the number of its actual inhabitants, if compared with the other Italian regions. However, Abruzzo is among the first Italian regions, both for quality and quantity, on the American soil.

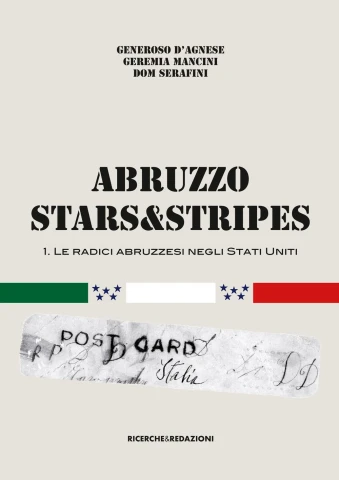

Recently, a very interesting book about the relationship between Abruzzo and the United States has been released in Italy. We talk about this book with one of its three authors, a great expert of Abruzzese emigration in the world, Generoso D'Agnese.

Generoso, you have been describing the Abruzzese emigration for years and wrote several works on this subject. Recently, you have published the book "Abruzzo Stars & Stripes. Le radici abruzzesi negli Stati Uniti. Vol. 1" with Dom Serafini and Geremia Mancini. Tell us something about it.

“Abruzzo Stars & Stripes” represents the new stage of a journey that began in 1990 when, by pure chance, I began to write about Italians in the World. To me, a son of emigrants, born and raised abroad, looking for news about our fellow countrymen seemed quite natural; even though my main dream was to become a scientific journalist.

I made this choice because of a magazine that is still published today in Pescara and with whom I passionately work with: Abruzzo nel Mondo – Abruzzo in the World. For 35 years, this magazine has collected news from the communities from Abruzzo and Molise in the World, and it has been sent to thousands of families. Until a few years ago, it was sent even to New Caledonia, which had a small community emigrated from Ortona (Chieti). Therefore, I approached the emigration world and, after several years, I was given an opportunity by the newspaper America Oggi in New York. I was asked to write ten articles about Italians in the United States, and, after the first series of articles, which appeared in the column called “Protagonisti Italiani in America,” they asked me to write more. The collaboration continues and, so far, I've published about 700 articles on Italian stories in the United States.

Thanks to the friendship with Dom Serafini, publisher of “Video Age International,” years ago we created "AbruzzoAmerica," a project that led to the publication of a book with the same title in 2003, which collected several stories of Americans from Abruzzo. Since then, our common commitment has continued, and along the way it has also incorporated our friend Geremia Mancini, who has been collecting stories of Americans from Abruzzo and Molise too.

This has been the premise of the new book, which tells the lives of 64 Abruzzo characters who have somehow left a mark in the United States. These should be added to at least 90 other characters, who will appear in the second volume which will be released in December, and perhaps even more people, who we would like to collect in a third volume.

In the book, we deliberately left the specific style of each author. Therefore, the stories have a length and a rhythm of reading different from one author to the other, in order to allow the reader to confront different narrative styles. But what unites all of us is the desire to pay tribute to all the men and women who, with immense sacrifices and special insights, have spent their time conquering a slice of the American dream.

In the first volume, the stories are almost always in the past, and for this reason the subtitle speaks of "roots of Abruzzo in the United States". Even the title, “Abruzzo Stars & Stripes”, composed by both an Italian and two English words, emphasizes the desire to tell the stories of a "fusion" between the two cultures.

Will the book be published in English, therefore available in the United States as well?

For now, the idea is to complete the second volume and then eventually work on a third volume to collect other interesting stories.

At the same time, Geremia Mancini and I are working on another book about Molisian stories in America. Only after completing these three projects will we think about an English translation, but if an Italian publisher in the US shows an interest in this hypothesis, we would be happy to be able to offer the book to readers who are of Italian origin but have little knowledge of the beautiful but difficult Italian language.

Today, many Abruzzesi communities (but the debate applies in general to all Italian communities) in the United States have maintained a strong link with regional traditions but they have lost their linguistic abilities; even though, sometimes a few “dialectical islands,” which are very interesting for the study of linguistic anthropology, exist among the communities.

What is the history of emigration from Abruzzo to the United States?

Abruzzo's migratory history in the United States aligns with the historical flow that brought millions of Italians to the opposite shores of the Atlantic. A story that began after the unification of Italy and ended in the late eighties of the twentieth century.

Abruzzo was strongly attracted to the Americas. The province of Chieti recorded, from the beginning, percentages of departures to the American continent that involved about 100% of the total emigration all over the world: between 1876 and 1905, out of 115,199 expats, 110,873 emigrated to America. From the Statistical Yearbook of Emigration, moreover, we know that between 1876 and 1925, 1,049,735 Abruzzesi and Molisani emigrated; 911,194 of these made their way to America, and among them, 628,441 in the United States.

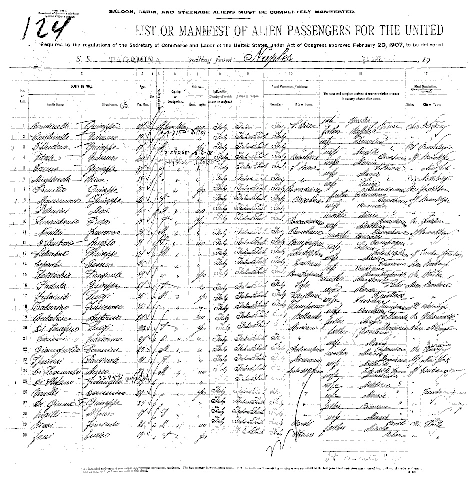

The American destination represented about 87% of Abruzzo and Molise emigration until the Second World War. So, much of the Abruzzesi emigrants who went to America in the early decades of the twentieth century chose the United States. Almost everyone of them landed at Ellis Island, the first (terrible) impression with the great American nation. For some it was the beginning of a new life, for others a bitter disappointment.

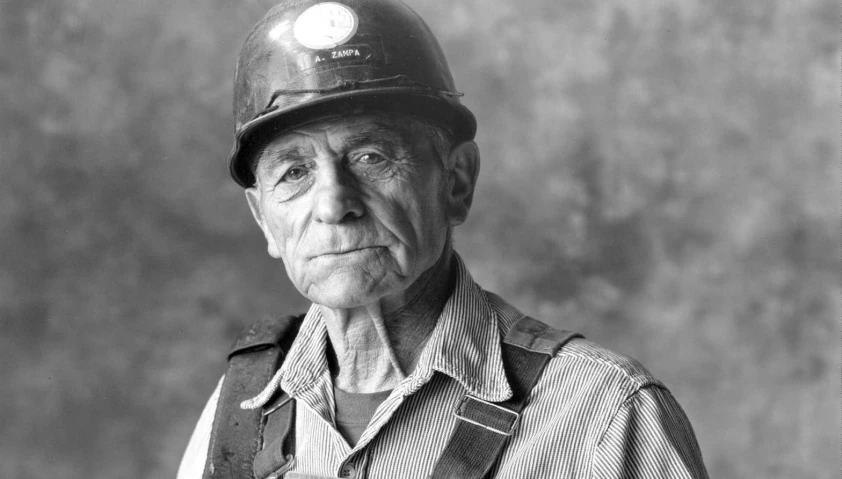

Most of the Abruzzesi moved to areas rich in mines and iron and steel industries. The presence of mountains and caves in Abruzzo made possible the presence of many mining workers who, once arrived to the United States, went to enrich the mass of miners employed in often crumbling and dangerous installations. It is no coincidence that so many Abruzzesi died in 1907 in the disaster of the Monongah mine. After this first phase, the craftsmanship and manufacturing of Abruzzo immigrants began. Many tailors, for example, slowly conquered their American dream by opening tapestries and manufacturing factories.

Your book has many interesting stories. One of these is for example the story of Al Zampa, whom is dedicated the second "Italian" bridge in the United States after the Verrazzano one: the Alfred Zampa Memorial Bridge in San Francisco ...

Alfredo Zampa was born in 1903 in Selby, California, probably by the name Amedeo, son of Andrea (however called Emilio) and grandson of Gaetano Zampa. He lived until the age of 95 and defined his existence "halfway between hell and paradise".

For 45 years Al Zampa worked on the steel ropes of American bridges, a skilled worker in the construction and maintenance of suspended giants on the water, sharing with his brother and two sisters the dignified life of the Italian community of the San Francisco bay. Alfredo grew up with the typical difficulties of integration, not being able to count on a regional core similar to his own traditions. In an area marked by the great presence of Sicilian and Ligurian communities (mostly fishermen transformed into merchants), the young Marsican grew up with the myth of his land, which unfortunately he never saw. However, he traveled with his imagination through mom and dad’s stories, pushing his luck continuously with his own existence.

In an October 1936 day, he fell down from the scaffolding of the famous Golden Gate Bridge of San Francisco, a flight of hundreds of meters high, crashing on the underlying rocks, saved by the miraculous action of some security nets. The young worker survived but broke four vertebrae and became the living example of a miracle among the many fellows involved in the scaffolding of the shipyards. He became a true hero after four years of hard hospitalization at St. Luke Hospital when he decided, against everyone's opinion, to return to work on the bridges of America.

But his leap of faith did not leave the tenacious Italian indifferent. Recalling his incident, Al Zampa gave birth to an association called "Halfway between paradise and hell", engaged in supporting all the battles of his category, in favor of safer work. And he continued his work for almost 50 years, a tireless specialized worker on the most famous bridges in California, Texas, Arizona and upstate New York.

He died in 2000, at the age of 95, and after just three years the State of California wanted to pay homage to him, inaugurating the ”Alfred Zampa Memorial Bridge”.

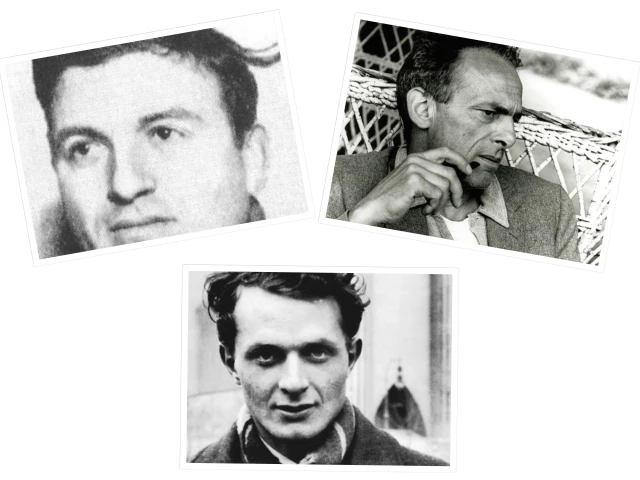

Another story I was curious about is that of Vincenzo Pelliccione, who was Charlie Chaplin's body double for years

Vincenzo Pelliccione was born in Rosciolo, in the province of L'Aquila, on June 2, 1893- Following the migrant tide of late nineteenth century, Vincenzo left at age 22 after the 1st world war leaving Abruzzo and his 5 brothers to go to Pennsylvania. When he arrived in the United States, Vincenzo adapted himself to working in the most diverse fields. With a few dollars he was able to pay a course to learn the English language rudiments and after a few years he moved to Ohio to finally arrive in Hollywood in1929, a city that was experiencing the first big movie industry boom.

A great admirer of the early movie stars, Vincenzo was fascinated by Charlie Chaplin's comic movements and casually discovered that he knew how to imitate them perfectly. Repeating the gesture in front of the mirror, he also discovered that he resembled the great "Charlot" and worked on this similarity by perfecting the imitation of a character who would "nourish" him professionally. The actor from Marsica began to propose imitating performances in small cafes and restaurants in Hollywood, and in one of these many evenings he was spotted by Sid Groeman, an American impresario owner of "Groeman's Chinese Theater": now a place known for the custom, by celebrities, to leave hands imprints on the sidewalk outside.

Within a few days Vincenzo was brought to Charlie Chaplin's studio. The great actor needed a body double and the Marsican actor was the right person. He became Eugene De Verdi and left his signature on numerous films, among which we should mention "The Circus", "The Great Dictator", "City Lights" and "Modern Times." Because of the perfect physical resemblance, Groeman hired him for five years in a row. In addition to being Chaplin’s body double, Pelliccione replaced him in all the advertising spots of his movies. Groeman also hired him to go on stage in various American locations and to advertise films which then earned millions.

Beyond the role of Chaplin’s body double, Pelliccione’s career was full of numerous cameos. He met Mae West, Jean Harlow and Marylin Monroe; he met Liz Taylor on the set of Cleopatra; and while working in the film "The Rose Tattoo", he met Anna Magnani. He also was with Rodolfo Valentino in the film "Son of the Sheikh".

Over the years, Pelliccione developed a great talent for the set designs and special effects, inventing different machines to be used on the movie sets. As a technical consultant he took part in the movies "Teresa" and Disney’s "Twenty Thousand leagues under the sea”, for which he won an Oscar in 1955 for special effects. He also collaborated with the production of "Ben Hur" and “Cleopatra".

In 1968 Pelliccione decided to leave Hollywood and returned to Italy to work at Cinecittà. For ten years, until the day of his death, he collaborated with the artist Enzo Carnebianca for the film productions of Dino De Laurentiis, enrolling his name among the most important special effects specialists. He is among the Italians who made Hollywood great.

Among the stories that inspire you, are there any you are particularly attached to? Maybe one about women?

The book is made up of stories told by three authors. As for my contribution, I particularly like the story of the Francese brothers and that of Virgilia D'Andrea.

Born in Chieti, Turzo and Alfonso Francese arrived to Ellis Island in 1913, traveling unbeknownst to each other, in the same "Verona" ship after Grandma Rosa Vassetta boarded them to reach their father Filippo. They were unlucky children. After a useless attempt of cohabitation and the umpteenth aggression by their stepmother, the two brothers decided to leave their father's home and wandered around the city. At day they would attend school, at night they would hang out together with other desperate people.

Their father had signed the papers to get them accepted in the Dominican sisters' college and subsequently signed his consent for adoption by parents of different religions than the Catholic one. In 1919, after six years of difficult street life, the Francese brothers were put on the orphans’ train founded by Charles Loring Brace (a Methodist Protestant pastor who founded the Children's Aid Society in 1853) destined to reach Texas and New Mexico. At each stop they came down from the train to get in line and wait for a new family to choose them. The two slender children, arrived ‘til the end of the trip in Denton, along with other 10 children nobody wanted.

Finally, Ruben Rucker chose Alfonso and brought him to Krum, Texas. Turzo (who had become Mike in the meantime) was severely ill and thanks to a doctor's visit he found a family. The doctor signaled the possibility of adopting him to his nephew Hazen Armstrong, a 19-year-old boy who had just married and was starting his career as a horse breeder. Mike was adopted by Hazen who for the rest of his life thought he had adopted an eight-year-old boy (while Turzo was actually nearly fifteen), which allowed him to attend a Catholic school. Mike became a good accountant, Al became an engineer and worked in the railways.

Virgilia D'Andrea was born in 1888 in Sulmona, in Abruzzo, where she spent her childhood. She became orphan of her mother at six and later also of her father, who was killed by his second wife for trivial reasons related to their relationship. Among the walls of the college, Virgilia was passionate about literature and found comfort in poetry. After graduating, the girl took refuge in studying and refined her sensitivity.

The murder of King Umberto II by the anarchist Bresci entered her life as a devastating deflagration. At that criminal gesture, Virgilia D'Andrea tied her personal social redemption against all rules and impositions. In those years Virgilia discovered the poetry of Ada Negri and, through her rhymes, the real motive that had pushed Bresci to his extreme act: a retaliation for massacring the innocent.

The discovery of social justice literally changed the perspective of things for a girl forced into the narrow walls of an institute. After studying so much at the University, Virgilia began teaching for some years in Abruzzo but a few weeks after the announcement of Italy entering the First World War, she definitively left the native land and entered the active military by participating in anti-interventionist agitations. In a few weeks she became an anarchist militant.

In 1917, during a clandestine meeting of the Unione Sindacale Italiana (Italian Trade Unions) called for the reaffirmation of the non-belligerent position of Italy, Virgilia met and fell in love with Armando Borghi. A strong supporter of the individualist act and of revolutionary violence, Virgilia became the publisher of the small newspaper "La Veglia", and went allaround the United States giving lectures and conferences in hovels, public parks, and other outdoor venues. Thanks to her and other women’s social activism, like Angela Bambace, Tina Catania, Antonietta Lazzaro, Tina Gaeta, Margaret of May, Lucia Romualdi and Albina Delfino, 60,000 workers, mostly women, participated to the most massive strike of the Great Depression years in New York. The worsening of her health turned the year 1932 into the crucial moment of her life. In 1933 she died, mourned by so many people: Virgilia D'Andrea was a writer, a poet, an editorialist and a propagandist of the anarchist cause.

Can you give us some details about Abruzzo's presence in the United States today? How many Abruzzesi are there, where they are, and from which cities their families came from?

Today, most of the Abruzzesi are concentrated around the two areas of Philadelphia and Boston. The Abruzzesi communities amounts to about 200,000 compatriots, while another very big community lives in Ontario. A significant presence also lives in Ohio where for example, Dean Martin and Henry Mancini were born. New York and California close this theoretical ranking: but in the Big Apple one of the most active Abruzzese associations in the World operates, the association of many countrymen from Orsogna, in the province of Chieti. In the same province there is also Carunchio: paradoxically, we have a town of origin that has 600 inhabitants and a community in America of 15,000 units that come from there. Other communities among the most present are those that refer to Pacentro (L'Aquila), Popoli (Pescara) and Roseto (Teramo).

Is there an official association representing the Abruzzesi in the United States of America?

There is no specific association, but there is a Federazione delle Associazioni Abruzzesi based in Boston which collects a good number of subscribers around.

In your opinion, is there a peculiarity that characterizes the Abruzzesi in America and differentiates them from the other Italian Americans?

After many years of research about the Italians around the world, we have noticed that Abruzzo has a larger percentage of artists in comparison with other Italian communities. Artists such as Henry Mancini, Perry Como, Dean Martin are just the tip of an iceberg made up of so many personalities who are cast in some artistic form: John Fante, Peter Di Donato and Pascal D'Angelo, for example, left great marks in the narrative. And we could cite Suzi Quatro, Madonna, Patti LuPone and Penny Marshall among the talents of music, theater and film and television. It's as if talent came out of a DNA hardened for centuries of tiring life.

Of course, this must be related to the number of immigrants. In Italy, Abruzzo numerically represents a small medium region with its 1,300,000 inhabitants, while regions such as Sicily, Campania, Veneto and Piedmont count a much larger number of emigrants. Another trait of Abruzzo community is to be very attached to their food traditions and dialect, and also to be less inclined to media exposure. There is a sort of basic decency that distances the Abruzzesi who live in the United States from media overexposure. Though, they change and become much more sparkling during the festivals that remind them of the patrons of their communities.

Chi conosce le dinamiche dell’emigrazione italiana in America sa bene che l’Abruzzo ricopre percentualmente un ruolo ben più grande di quello che ha in Italia quanto a grandezza del suo territorio e al numero dei suoi abitanti. In terra americana, invece, sia qualitativamente che quantitativamente l’Abruzzo è tra le prime regioni italiane.

E’ da poco uscito in Italia un bel libro che parla del rapporto tra Abruzzo e Stati Uniti. Ne parliamo con uno dei tre autori, un grande conoscitore di emigrazione abruzzese nel mondo, Generoso D’Agnese.

Generoso, da anni ti occupi di emigrazione abruzzese e hai scritto diverse opere a questo proposito. Recentemente, insieme a Dom Serafini e Geremia Mancini, hai pubblicato il libro "Abruzzo Stars&Stripes. Le radici abruzzesi negli Stati Uniti. Vol. 1". Ci dici qualcosa in più?

“Abruzzo Stars & Stripes” rappresenta una nuova tappa di un percorso iniziato nel 1990 quando per puro caso ho iniziato a scrivere sugli italiani nel Mondo. Per me, figlio di emigranti, nato e vissuto all’estero, cercare notizie sui nostri connazionali mi è sembrato del tutto naturale, pur essendo partito con l’idea del giornalismo scientifico.

Artefice di tale scelta è stato un periodico che ancora oggi viene pubblicato a Pescara e con il quale collaboro con grande passione: Abruzzo nel Mondo. Da 35 anni questo periodico raccoglie notizie della comunità abruzzese e molisana nel Mondo e viene inviato a migliaia di conterranei. Fino a pochi anni fa arrivava perfino in Nuova Caledonia dove ancora vive una piccola comunità emigrata da Ortona (Chieti). Mi sono pertanto avvicinato al mondo delle migrazioni e dopo diversi anni di lavoro mi è stato offerta un’opportunità dal giornale America Oggi di New York. Mi si chiedeva di scrivere una decina di articoli sugli italiani negli Stati Uniti e dopo la prima serie di articoli apparsi nella rubrica Protagonisti Italiani in America, mi hanno chiesto altri articoli. La collaborazione continua ancora e finora ho pubblicato circa 700 articoli sulle storie italiane negli Stati Uniti.

Grazie all’amicizia di Dom Serafini, editore di Video Age International anni fa nacque il progetto “AbruzzoAmerica” che portò alla pubblicazione di un omonimo libro nel 2003 che raccoglieva diverse storie di abruzzesi nelle Americhe. Da allora il nostro impegno comune è continuato e strada facendo ha inglobato anche l’amico Geremia Mancini che da qualche anno ha iniziato a sua volta a ritrovare e recuperare storie di abruzzesi e molisani.

Tutto questo è la premessa al libro che racconta le vite di 64 personaggi abruzzesi che hanno in qualche modo lasciato un segno nei confini statunitensi. A questi bisognerebbe aggiungerne almeno 90 previsti per il secondo volume in pubblicazione a dicembre e forse ancora altri che vorremmo raccogliere in un terzo volume.

Nel libro abbiamo lasciato volutamente l’impronta specifica di ogni autore. Le storie hanno pertanto lunghezza e ritmo di lettura diverso da un autore all’altro, onde permettere al lettore di confrontarsi con stili narrativi diversi. Quello che però accomuna tutti noi è la voglia di rendere omaggio a uomini e donne che con immensi sacrifici e particolari intuizioni hanno attraversato il loro tempo conquistando una fetta del sogno americano.

Nel primo volume le storie sono quasi tutte volte al passato, ed anche per questo motivo il sottotitolo parla di “radici abruzzesi negli Stati Uniti”. Lo stesso titolo “Abruzzo Stars & Stripes”, composto in parte da una parola italiana e dall’altra di parole inglesi, sottolinea la voglia di raccontare le storie di una “fusione” tra le due culture.

E' prevista la pubblicazione del libro anche in lingua inglese per il mercato americano?

Per ora l’idea è quella di completare il secondo volume e poi eventualmente lavorare a un terzo volume per raccogliere altre storie interessanti.

Contemporaneamente con Geremia Mancini stiamo lavorando a un altro libro che riguardi invece le storie molisane in America. Soltanto dopo aver completato questi tre progetti penseremo a una traduzione in inglese, ma se nel frattempo un editore italiani negli USA mostrerà interesse a questa ipotesi saremmo lieti di poter offrire il libro anche a lettori che sono di origine italiana ma hanno poca dimestichezza con una lingua bellissima ma difficile come l’italiano.

Oggi molte comunità abruzzesi (ma il discorso vale in generale per tutte le comunità italiane) presenti negli Stati Uniti hanno mantenuto un forte legame con le tradizioni regionali ma hanno perso la capacità linguistica, anche se tra loro resistono isole dialettali molto interessanti per lo studio dell’antropologia linguistica.

Qual è la storia dell'emigrazione dall'Abruzzo agli Stati Uniti?

La storia migrazionale abruzzese negli Stati Uniti si allinea al flusso storico che portò milioni di italiani sulle rive opposte dell’Atlantico. Una storia iniziata all’indomani dell’Unità d’Italia e terminata sul finire degli anni ’80 del Ventesimo Secolo.

L’Abruzzo fu fortemente attratto dal Continente Americano. La provincia di Chieti fece registrare, sin dall’inizio, percentuali di partenze verso il continente americano che interessarono circa il 100% del totale dell’emigrazione: tra il 1876 ed il 1905, su 115.199 espatri ben 110.873 emigrarono verso l’America. Dall’Annuario statistico dell’emigrazione si rileva, inoltre, che tra il 1876 ed il 1925, 1.049.735 abruzzesi e molisani emigrarono; di questi ben 911.194 si diressero verso l’America di cui 628.441 negli Stati Uniti.

La destinazione americana ha rappresentato circa l’87% dell’intera emigrazione abruzzese e molisana fino alla seconda guerra mondiale. Molta parte degli emigranti abruzzesi che si diresse verso l’America nei primi decenni del Novecento scelse quindi di tentare la fortuna negli Stati Uniti. Di questi, quasi tutti sbarcarono ad Ellis Island, primo (terribile) impatto con la grande nazione americana. Per alcuni rappresentò l’inizio di una nuova vita, per altri un’amara delusione.

La gran parte degli abruzzesi si diresse verso le zone ricche di miniere e di industrie siderurgiche. La presenza di montagne e di cave in Abruzzo creò molti operai minerari che una volta giunti negli Stati Uniti andarono ad arricchire la massa di minatori impiegati in impianti spesso fatiscenti e pericolosissimi. E non è un caso che tanti abruzzesi morirono nel disastro della miniera di Monongah del 1907. Dopo questa prima fase, prese piede il tessuto artigianale e manifatturiero degli immigrati abruzzesi. Furono tanti i sarti ad esempio che pian piano conquistarono il loro sogno americano aprendo sartorie e fabbriche di manifattura.

Sono tante le storie molto interessanti contenute nel vostro libro. Una di queste è ad esempio quella di Al Zampa, a cui è dedicato il secondo ponte “italiano” negli Stati Uniti, dopo quello di Verrazzano: l’Alfred Zampa Memorial Bridge di San Francisco…

Alfredo Zampa era nato nel 1903 a Selby, in California, ma probabilmente con il nome di Amedeo, figlio di Andrea (chiamato però Emilio) e nipote di Gaetano Zampa. Visse fino all’ età di 95 anni e definì la sua esistenza “a metà strada tra l’inferno e il paradiso”.

Per 45 anni Al Zampa lavorò sulle funi d’acciaio dei ponti americani, operaio specializzato nella costruzione e nella manutenzione dei giganti sospesi sull’acqua, condividendo con il fratello e due sorelle la vita dignitosa della comunità italiana della baia di San Francisco. Alfredo crebbe nelle difficoltà tipiche dell’integrazione, non potendo contare neppure su un nucleo regionale affine alle proprie tradizioni. In un’area segnata dalla grande presenza di nuclei siciliani e liguri (in gran parte pescatori trasformatisi in commercianti), il giovane marsicano crebbe con il mito della sua terra, che purtroppo non vide mai. Viaggiò però con la fantasia attraverso i racconti di mamma e papà, trasformando la propria esistenza in una continua sfida alla fortuna.

In una giornata di ottobre del 1936 cadde giù dal ponteggio del famoso Golden Gate di San Francisco, un volo da centinaia di metri d’altezza, precipitando sulle rocce sottostanti, salvato dalla miracolosa azione di alcune reti di protezione. Il giovane operaio se la cavò con la rottura di quattro vertebre ma divenne l’esempio vivente dei miracoli tra i tanti connazionali impegnati sulle impalcature dei cantieri. Divenne un vero eroe, dopo quattro anni di duro ricovero al St. Luke Hospital, quando decise, contro il parere di tutti, di tornare a lavorare sui ponti d’America.

Ma il volo nel vuoto non lasciò insensibile il tenace italiano. Ricordando il suo incidente, Al Zampa diede vita all’associazione chiamata “A metà strada tra il paradiso e l’inferno”, impegnandosi a sostenere tutte le battaglie della categoria, in favore di un lavoro più sicuro. E continuò il suo lavoro per quasi dieci lustri, instancabile operaio specializzato sui ponti più celebri della California, del Texas, dell’Arizona e dello stato di New York.

Al è morto nel 2000, a 95 anni, e dopo soli tre anni lo Stato della California ha voluto rendergli omaggio inaugurando l’Alfred Zampa Memorial Bridge.

Un'altra storia che mi ha incuriosito è quella di Vincenzo Pelliccione, che fu per anni la controfigura di Charlie Chaplin

Vincenzo Pelliccione era nato a Rosciolo in provincia de L'Aquila il 2 giugno del 1893, e seguendo la marea migrante di fine Ottocento, Vincenzo partì all’età di 22 anni alla volta della Pennsylvania lasciando in Abruzzo i suoi cinque fratelli e una guerra mondiale. Arrivato negli Stati Uniti Vincenzo si adattò a lavorare nei campi più disparati. Con pochi dollari riuscì a pagarsi un corso per imparare i rudimenti della lingua inglese e dopo pochi anni si trasferì in Ohio per giungere infine nel 1929 a Hollywood, città che stava vivendo il primo grande boom dell’industria cinematografica.

Grande ammiratore dei primi divi del cinema, Vincenzo rimase folgorato dalle movenze comiche di Charlie Chaplin e scoprì casualmente di saperlo imitare perfettamente. Ripetendo le gesta davanti allo specchio scoprì inoltre di assomigliare tantissimo al grande “Charlot” e lavorò su tale somiglianza perfezionando l’imitazione di un personaggio che lo avrebbe “nutrito” professionalmente. Il marsicano iniziò a proporre spettacoli di imitazione in piccoli localini e ristoranti di Hollywood e in una delle tante serate fu adocchiato da Sid Groeman, un impresario americano proprietario del "Groeman's Chinese Theatre", oggi luogo conosciuto per l’usanza, da parte delle celebrità, di lasciare le impronte delle loro mani sul marciapiede antistante.

Nel giro di qualche giorno Vincenzo si ritrovò catapultato nello studio di Charlie Chaplin. Il grande attore aveva bisogno di una controfigura e il marsicano era la persona giusta. Divenne Eugene De Verdi e lasciò la sua firma su numerosi film, tra i quali va citato “Il Circo”, “Il Grande Dittatore”, “Luci della Città” e “Tempi moderni”. Per la sua perfetta rassomiglianza fisica, Groeman lo ingaggiò per cinque anni di seguito. Oltre a essere la controfigura di Chaplin, Pelliccione lo sostituì in tutti i lanci pubblicitari dei film. Groeman lo ingaggiò per salire sul palcoscenico in varie località americane e per pubblicizzare le pellicole che poi incassavano milioni di dollari.

La carriera di Pelliccione fu costellata di tante partecipazioni cinematografiche che andarono oltre il ruolo di controfigura di Chaplin. Conobbe Mae West, Jean Harlow e Marylin Monroe, sul set di Cleopatra conobbe Liz Taylor e mentre lavorava nel film "La rosa tatuata" incontrò Anna Magnani. Recitò inoltre accanto a Rodolfo Valentino nel film “Il figlio dello Sceicco”.

Con il passare degli anni, Pelliccione sviluppò un ottimo talento per le scenografie e per gli effetti speciali, inventando diverse macchine per i set. In qualità di tecnico partecipò ai film “Teresa” e a “Ventimila leghe sotto i Mari” della Disney, per i quali vinse nel 1955 un premio Oscar per gli effetti speciali. Collaborò anche con la produzione di “Ben Hur” e di Cleopatra”.

Nel 1968 il marsicano decise di lasciare Hollywood e rientrò in Italia per lavorare a Cinecittà. Per dieci anni e fino al giorno della sua morte, collaborò con l’artista Enzo Carnebianca alle produzioni cinematografiche della Dino De Laurentiis iscrivendo il suo nome tra quello dei grandi specialisti degli effetti speciali. E’ tra gli italiani che fecero grande Hollywood.

Ci sono un paio di storie tra le tante raccontate alle quali ti sei appassionato in particolare? Magari una femminile?

I libro è fatto di storie raccontate attraverso tre autori. Per quanto riguarda il mio contributo, amo particolarmente la storia dei fratelli Francese e quella di Virgilia D’Andrea.

Nati a Chieti, Turzo e Alfonso Francese arrivarono a Ellis Island nel 1913, viaggiando all’insaputa uno dell’altro, nella stessa nave “Verona” dopo esservi stati imbarcati dalla nonna Rosa Vassetta per farli raggiungere il padre Filippo. Furono bambini sfortunati. Dopo un’inutile tentativo di coabitazione, i due fratelli decisero di lasciare la casa del padre, dopo l’ennesima aggressione da parte della matrigna, e vagarono per la città. Di giorno frequentavano la scuola, di notte si univano ad altri sbandati per farsi coraggio.

Il loro padre aveva firmato intanto le carte per farli accogliere nel collegio delle sorelle domenicane e successivamente firmò anche il suo consenso per un’adozione presso genitori di religione diversa da quella cattolica. Nel 1919, dopo sei anni di difficilissima vita di strada, i fratelli Francese vennero messi sul treno degli Orfani fondato da Charles Loring Brace (un pastore protestante metodista e fondatore della “Children’s Aid Society” nel 1853), per raggiungere il Texas e il New Mexico. Ad ogni fermata scendevano dal treno per mettersi in fila e attendere una eventuale scelta da parte di nuove famiglie. I due bambini, gracili, arrivarono al capolinea, a Denton, insieme ad altri 10 bambini ancora senza sistemazione.

Per Alfonso si presentò infine Ruben Rucker che scelse il ragazzo portandolo a Krum, in Texas. Turzo (divenuto intanto Mike) si era invece gravemente ammalato e fu proprio grazie alla visita del dottore che egli trovò famiglia. Il medico segnalò la possibilità di adozione a suo nipote Hazen Armstrong, un ragazzo di 19 anni che si era appena sposato e stava iniziando il mestiere di allevatore di cavalli. Mike venne adottato da Hazen che per tutta la vita pensò di aver dato un padre a un ragazzo di otto anni (ne aveva quasi quindici), permettendogli di frequentare una scuola cattolica. Mike divenne un bravo amministratore contabile, Al è diventato invece ingegnere e ha lavorato nelle ferrovie.

Virgilia D’Andrea era nata invece nel 1888 a Sulmona, e in Abruzzo visse gli anni della sua infanzia, orfana di madre a poco più di sei anni e del padre ucciso per futili motivi amorosi dalla seconda moglie. Tra le mura del collegio Virgilia si appassionò alla letteratura e trovò conforto nelle poesie. Conseguito il diploma magistrale, la ragazza si rifugiò ancora di più nello studio e affinò la sua sensibilità.

L’omicidio di re Umberto II per opera dell’anarchico Bresci entrò nella sua vita come una deflagrazione devastante. A quel gesto criminale, Virgilia D’Andrea legò il suo personale riscatto sociale contro tutte le imposizioni regolamentari. Saranno questi gli anni in cui Virgilia avrebbe scoperto la poesia di Ada Negri e attraverso le sue rime il vero motivo che aveva spinto Bresci all’atto estremo: una ritorsione per aver massacrato degli innocenti.

La scoperta della giustizia sociale, per una ragazza costretta tra le anguste mura di un istituto, cambiò letteralmente la prospettiva delle cose. Terminati gli studi e l’Università, Virgilia iniziò ad insegnare per alcuni anni in Abruzzo ma poche settimane dopo l’annuncio dell’entrata in guerra nel primo conflitto mondiale, lasciò definitivamente la terra natale ed entrò nella militanza attiva partecipando alle agitazioni anti-interventiste. In poche settimane divenne una militante anarchica a tutti gli effetti.

Nel 1917, proprio durante una riunione clandestina dell’Unione Sindacale Italiana (USI), indetta per riaffermare la posizione non belligerante dell’Italia, la ragazza incontrò Armando Borghi e se ne innamorò. Convinta assertrice dell’atto individualistico e della violenza rivoluzionaria, Virgilia divenne editrice di un piccolo giornale “La Veglia”, e attraversò gli Stati Uniti tenendo comizi e conferenze nelle stamberghe, nei parchi pubblici, negli incontri all’aperto. Grazie al suo attivismo, e a quello di donne quali Angela Bambace, Tina Catania, Antonietta Lazzaro, Tina Gaeta, Margaret di Maggio, Lucia Romualdi e Albina Delfino, New York vide scendere in piazza 60mila lavoratori, in gran parte donne, in quello che divenne il più massiccio sciopero degli anni della Grande Depressione. Il peggioramento della salute trasformò il 1932 nel momento cruciale della sua vita. Nel 1933 morì, pianta da tante persone: con Virgilia D’Andrea si spegneva una scrittrice, poetessa, editorialista e propagandista della causa anarchica.

Ci puoi dare qualche dato sulla presenza abruzzese negli Stati Uniti oggi? Quanti sono, dove sono, di quali città abruzzesi sono originari?

Oggi la maggior parte degli abruzzesi è concentrata intorno alle due aree di Philadelphia e Boston. La comunità abruzzese ammonta a circa 200 mila conterranei e si specchia con la grande comunità abruzzese che vive nell’Ontario. Una presenza significativa si registra anche in Ohio dove sono nati ad esempio Dean Martin e Henry Mancini. New York e California chiudono questa classifica teorica ma proprio nella Grande Mela opera una delle associazioni più attive di abruzzesi nel Mondo, l’associazione che raggruppa molti conterranei provenienti da Orsogna, in provincia di Chieti. Nella stessa provincia è anche Carunchio: paradossalmente abbiamo un paese d’origine che conta 600 abitanti e una comunità in America che arriva a 15 mila unità. Altre comunità tra le più presenti sono quelle che fanno riferimento a Pacentro (Provincia de L'Aquila), Popoli (Provincia di Pescara) e Roseto (Provincia di Teramo).

C'è un'associazione ufficiale che rappresenta gli abruzzesi negli Stati Uniti d'America?

Non esiste un’associazione specifica ma una Federazione di Associazioni Abruzzesi che ha sede a Boston e raccoglie intorno a se un buon numero di iscritti.

A tuo avviso, c'è una particolarità che contraddistingue gli abruzzesi in America dagli altri italoamericani?

Facendo da tanti anni ricerche sugli italiani nel Mondo, abbiamo notato che l’Abruzzo conta, percentualmente un grande numero di artisti rispetto ad altre comunità italiane. Artisti come Henry Mancini, Perry Como, Dean Martin rappresentano solo la punta di un iceberg fatto di tante personalità votate a una qualche forma artistica: John Fante, Pietro Di Donato e Pascal D’Angelo ad esempio hanno lasciato grandi segni nella narrativa. E potremmo citare Suzi Quatro, Madonna e Patti LuPone, Penny Marshall tra i talenti della musica, del teatro e del cinema e televisione. E’ come se il talento venisse fuori da un DNA temprato da secoli di vita faticosa.

Tutto questo ovviamente bisogna rapportarlo al numero degli immigrati. In Italia, l’Abruzzo numericamente rappresenta una regione medio piccola con i suoi 1 milione e 300 mila abitanti mentre regioni come la Sicilia, la Campania, il Veneto e il Piemonte contano un numero ben maggiore di emigrati. Altro tratto delle comunità abruzzesi è quello di essere molto legati alle tradizioni dialettali e agroalimentari, e anche di essere poco inclini all’esposizione mediatica. C’è una sorta di pudore di fondo che allontana gli abruzzesi residenti negli Stati Uniti dalla sovraesposizione mediatica. Per poi sciogliersi nelle feste che ricordano i patroni delle loro comunità.