During World War II more than 51,000 Italian soldiers were brought to the United States as Prisoners of War. The award-winning documentary film “Prisoners in Paradise,” recounts the story of the young soldiers brought to the US as POWs, their romances and friendships with American women, their contribution to the Allied war effort, and — for some — their decision to return to live in the US.

We are happy to speak about this with the Italian American director and producer of this very important documentary, Camilla Calamandrei, Welcome to We the Italians!

To begin with, could you please tell us about yourself and your Italian heritage?

My father, Mauro Calamandrei, was the first American Correspondent for L’Espresso and wrote for the weekly for many decades, later he was the American Cultural Correspondent for Il Sole 24 Ore. He was born to an extremely poor family outside of Florence, fought as a partisan in the resistance during WWII as a teenager, and went on to earn two PhDs. He first studied at the University of Florence, then he was awarded a Fulbright to study at the University of Chicago where he was delighted with the immense access to impressive open stack libraries and the intensity of the intellectual community. He lived in the New York City for the rest of his life, but always identified exclusively as an Italian. That Italian heritage is a big part of my identity as well. I am close with my Italian cousins, my son and I are dual citizens, we travel to Italy frequently and my very non-Italian husband is now studying Italian.

How did the idea for your wonderful documentary come about?

I had visited my aunt, uncle and cousins in Florence a number of times throughout my childhood, but I did not speak Italian so our conversations were limited. Then, once when I was visiting in my early twenties, my uncle (who didn't speak English and who had never been to the US during my lifetime) started to recount a story in Italian, “When I was a prisoner in America during the War…” I had no idea what he was talking about. I had never heard his story of being a POW, and I had no idea that there had been Italian prisoners of war in the US. He said (among other things) they would use a towel wrapped around a bed post to practice the “boogie-woogie to dance with American girls.” It was astounding.

I knew some of my father’s stories of fighting in the Resistance but didn’t know much about the experience of Italians who had been drafted and served in Mussolini’s army. I definitely knew nothing about the 600,000 who were taken as prisoners of war and dispersed around the globe. 51,000 of whom were brought to the US.

I started looking for information in books or films about Italian POWs in America but there was very little documented, just a handful of academic articles and one book by an energetic history buff, Louis Keefer.

Louis graciously shared his contacts with me so I could begin meeting with surviving POWs across the US. I worked on the film for 10 years, conducting preliminary interviews, doing background research with consulting scholars, fundraising, filming on location across the US and in Italy, unearthing archival footage and crafting the story.

Who are the Italians featured in the documentary?

I interviewed 19 surviving Italian POWs while researching the film, and then selected four POWs and two of their wives to film in the US, and three surviving POWs to film in Italy. Four of the men featured in the film served in Italian Service Units (ISU) supporting the US war effort in non-combat roles while they were POWs and two did not. Of the two who did not join an ISU, one regretted his decision later and wished he had supported the Allied war effort.

Italian prisoners were held in 26 different US states. What differences were there between the various locations?

The POWs I interviewed all had very similar descriptions of their experiences in the US. The first story every surviving POW told me about America was their shock at the abundance of food. One Italian officer in the film tells the story of when they were still captives in Africa held by the US military and a US soldier opened a can and pulled out an entire cooked chicken.

Another tells the story of his disbelief that so much food could be provided for enemy POWs, “this cannot be for us.” And yet another tells of POWs in Ogden, Utah hiding bread in the rafters of their barracks because they feared it would run out. The Americans couldn’t figure out how the Italian POWs were eating so much bread but eventually they discovered what was happening.

Each of the POWs I spoke with were amazed by the expansive vistas of open land they saw as they were being transported across the country by train. And their stories continued to be very similar regardless of where they were held in the US. Most documentaries might try to follow the separate details of each man’s story but there was so much overlap that we were able to make a tapestry of moments and experiences that add up to the story of all of them.

We took the beginning of each man’s story but then took the next piece from just one or two people, and the next piece from another. We didn’t need to revisit every step of each man’s story and yet you feel you have lived the unfolding story of each man.

What kind of interaction did the prisoners have with the Italian American community?

After the Italian armistice in September 1943, Italian POWs had the opportunity to join Italian Service Units (ISU) in non-combat roles to support the US war effort, doing laundry, farming, cooking, etc. They had to pledge allegiance to the new Italian government and were held in ISU camps across the US. Ninety percent of the Italians POWs agreed to serve in these ISUs and some of the work they did allowed them increased contact with Americans. In addition, at many of the ISU camps, Italian POWs were allowed Sunday visits from local Italian American families. On occasion, they were even permitted to attend community events outside the camps - always under supervision - or share meals with local families. Romances bloomed between POWs and local Italian American women, and some were quite serious.

In contrast, Italian POWs who refused to cooperate with the US war effort were sent to camps in Texas, where they endured stricter conditions and reduced food rations. I did find one American guard from Texas who became friendly with the POWs, but the non-ISU POWs had no regular contact with Italian American communities.

Is there any particularly interesting story or anecdote you'd like to share with our readers?

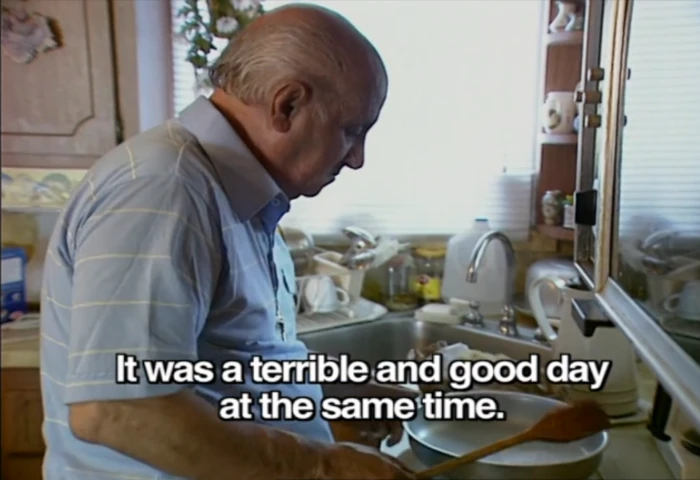

I like all the stories, but the story of Mario and Anna is particularly lovely. Mario had been a POW in Ogden, just outside of Salt Lake City, Utah. Anna and her family would come to visit on Sundays in hopes of finding POWs who might know their relatives in Italy. While Anna’s father was skeptical of the romance, he eventually gave his approval after questioning Mario’s intentions in a long conversation out in a freezing garage in winter. After the war, Mario was repatriated but Anna followed him there to get married. Anna would have stayed in Italy but there weren’t enough opportunities for Mario to work, and there were serious food shortages. So, together they returned to the US. They spent the rest of their lives in Ogden, the same town where he had served in an Italian Service Unit. They bought one of the decommissioned POW barracks, and converted it into their first home.

One touching detail that didn’t make it into the film is that Anna had always dreamed of moving to the West Coast as a young woman. But Mario became deeply attached to her family, so they stayed in Ogden and raised three children there. She never had the opportunity to live by the ocean, but she built a full, joyful life surrounded by family and grandchildren. Mario closes the film by saying, “Down deep, you love your country (Italy), but America gave to me everything.”

What happened to the prisoners after the end of the war?

By the end of the war, POWs serving in Italian Service Units had contributed millions of hours to the war effort, but none were offered the opportunity to remain in the US. In January 1946 all the POWs were repatriated, many leaving significant relationships with Italian American women behind — hoping, but not sure, that they would find a way to stay connected.

It was a devastating shock for the returning POWs to find so much of Italy destroyed in the war. And for Italian POWs who had not collaborated with the U.S., the return to Italy also meant coming to terms with the fact that in many cases friends and relatives had chosen to support the Allied war effort, and the non-collaborating position was no longer a popular one either officially or unofficially.

Some of the couples who had met in America did decide to marry. To do that, the American women had to go to Italy and marry there (because of quotas restricting immigration into the U.S.). Most often, due to financial difficulties in Italy, these couples returned to raise families in the US in the areas where the women had lived and where they still had jobs. We don’t know how many ex-POWs chose to come back and live in America but several in the film lived as American citizens in the towns where they were first enemy prisoners of war.

What has this story taught you?

I learned a great deal making the film but there are two things I would highlight.

One thing is obvious but, somehow, I hadn’t thought much about it before making the film. War is life changing, even for those who don’t see extensive battle, because of how it disrupts the course of young lives. It was eye opening for me to understand that teenagers are taken to be trained as soldiers and then kept in wartime service for years, depriving them of essential education, work experiences, and life experiences they would have had during that time. One of the POWs in the film worked as a laborer after the war and for all his life because he never finished school, but his other siblings had degrees and were professionals with very different lives – a stark example of how soldiers never get those years back.

The other thing I enjoyed learning was how powerful the connections were between Italians and Americans both before and after WWII. Long before World War II, there had been a steady flow of Italians coming to the US for work and then returning home, so the bond between Italy and the United States was already well established.

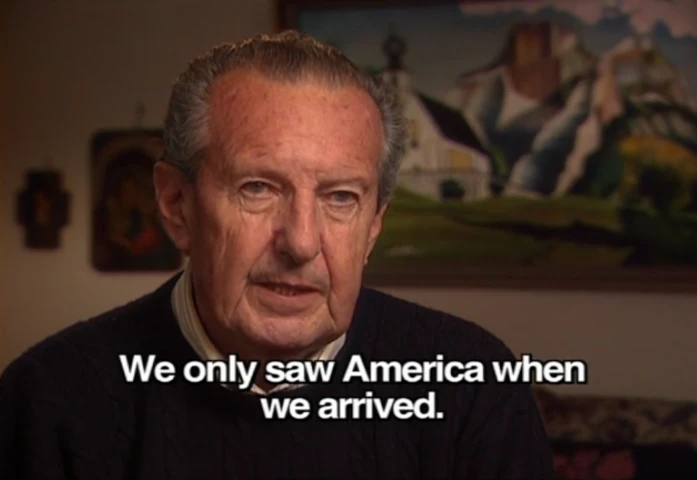

Italians had strong ideas about the US from people who had been here, but also from the movies. My uncle tells the story in the film of being captured in Northern Africa by the British and immediately turning to his friend and saying, “Let’s go with the Americans: things will be better with them!” So, they “escaped” from the British POWs to join the American POWs. Somehow, even then, they had this idea of America and were curious to experience it for themselves.

I am so happy I had the opportunity to make this film and provide a window into these stories - otherwise hidden in the margins of history.

You may read more about the film and the historical background at the film website: PrisonersInParadise.com.

Durante la Seconda guerra mondiale più di 51.000 soldati italiani furono portati negli Stati Uniti come Prigionieri di Guerra. Il film documentario pluripremiato “Prisoners in Paradise” racconta la storia dei giovani soldati condotti negli USA come prigionieri, delle loro storie d’amore e di amicizia con donne americane, del loro contributo allo sforzo bellico alleato e – per alcuni – della decisione di tornare a vivere negli Stati Uniti.

Siamo felici di parlare di tutto questo con la regista e produttrice italoamericana di questo importantissimo documentario, Camilla Calamandrei. Benvenuta su We the Italians!

Per cominciare, può parlarci di lei e delle sue origini italiane?

Mio padre, Mauro Calamandrei, è stato il primo corrispondente americano per L’Espresso e ha scritto per il settimanale per molti decenni; in seguito è stato il corrispondente culturale dagli Stati Uniti per Il Sole 24 Ore. Era nato in una famiglia estremamente povera fuori Firenze, combatté come partigiano nella Resistenza durante la Seconda guerra mondiale quando era ancora un adolescente, e poi conseguì due dottorati. Studiò prima all’Università di Firenze, poi ottenne una borsa Fulbright per studiare all’Università di Chicago, dove fu entusiasta dell’immenso accesso a impressionanti biblioteche a scaffale aperto e dell’intensità della comunità intellettuale. Visse a New York per il resto della sua vita, ma si identificò sempre esclusivamente come italiano.

Quell’eredità italiana è una parte importante anche della mia identità. Sono molto legata ai miei cugini italiani, mio figlio ed io siamo cittadini con doppia nazionalità, viaggiamo spesso in Italia e mio marito – che non ha origini italiane – ora sta studiando italiano.

Come è nata l’idea del suo splendido documentario?

Avevo visitato mia zia, mio zio e i miei cugini a Firenze diverse volte durante l’infanzia, ma non parlavo italiano, quindi le nostre conversazioni erano limitate. Poi, durante una visita quando avevo poco più di vent’anni, mio zio (che non parlava inglese e che non era mai stato negli Stati Uniti durante la mia vita) iniziò a raccontare una storia in italiano: “Quando ero prigioniero in America durante la guerra…”. Non avevo idea di cosa stesse parlando. Non avevo mai sentito la sua storia di prigioniero di guerra, e non sapevo che ci fossero stati prigionieri di guerra italiani negli Stati Uniti. Raccontò (tra le altre cose) che usavano un asciugamano avvolto attorno alla colonna del letto per esercitarsi nel “boogie-woogie per ballare con le ragazze americane”. Era sbalorditivo.

Conoscevo alcune delle storie di mio padre sulla Resistenza ma sapevo ben poco dell’esperienza degli italiani che erano stati arruolati e avevano servito nell’esercito di Mussolini. Sicuramente non sapevo nulla dei 600.000 che furono fatti prigionieri e dispersi in tutto il mondo, 51.000 dei quali furono portati negli Stati Uniti.

Iniziai a cercare informazioni in libri o film sui prigionieri di guerra italiani in America, ma c’era ben poco documentato: solo una manciata di articoli accademici e un libro di un appassionato di storia, Louis Keefer.

Louis condivise gentilmente i suoi contatti con me così da poter iniziare a incontrare i POW sopravvissuti in tutto il paese. Ho lavorato al film per 10 anni, conducendo interviste preliminari, facendo ricerche con studiosi consulenti, raccogliendo fondi, girando in varie località negli Stati Uniti e in Italia, portando alla luce filmati d’archivio e costruendo la narrazione.

Chi sono gli italiani presenti nel documentario?

Ho intervistato 19 prigionieri di guerra italiani ancora in vita mentre facevo ricerche per il film, poi ho selezionato quattro ex POW e due delle loro mogli da filmare negli Stati Uniti, e tre POW sopravvissuti da filmare in Italia.

uattro degli uomini presenti nel film servirono nelle Italian Service Units (ISU) a supporto dello sforzo bellico statunitense in ruoli non combattenti mentre erano ancora prigionieri, e due non lo fecero. Di questi ultimi, uno poi si pentì della sua decisione e avrebbe voluto aiutare lo sforzo alleato.

I prigionieri italiani furono detenuti in 26 diversi Stati americani. Che differenze c’erano tra le varie località?

I POW che ho intervistato raccontavano tutti descrizioni molto simili delle loro esperienze negli Stati Uniti. La prima cosa che ogni prigioniero ancora in vita mi disse dell’America fu il loro shock di fronte all’abbondanza di cibo. Un ufficiale italiano nel film racconta di quando erano ancora prigionieri in Africa sotto la custodia degli americani e un soldato statunitense aprì una scatola tirando fuori un pollo intero già cotto.

Un altro racconta la sua incredulità che così tanto cibo potesse essere destinato a prigionieri nemici: “Non può essere per noi.” Un altro ancora racconta dei POW a Ogden, nello Utah, che nascondevano il pane nelle travi dei loro alloggi perché temevano che sarebbe finito. Gli americani non riuscivano a capire come i prigionieri italiani mangiassero così tanto pane, finché alla fine scoprirono cosa stava accadendo.

Tutti i POW con cui ho parlato rimasero colpiti dagli immensi spazi aperti che vedevano mentre venivano trasportati in treno attraverso il paese. E le loro storie continuavano a essere molto simili a prescindere da dove fossero detenuti. La maggior parte dei documentari cercherebbe di seguire i dettagli delle storie di ogni uomo, ma c’era così tanta sovrapposizione che siamo riusciti a costruire un mosaico di momenti ed esperienze che insieme compongono la storia di tutti.

Abbiamo usato l’inizio della storia di ciascuno, poi il pezzo successivo solo da una o due persone, e poi un altro pezzo da un altro ancora. Non c’era bisogno di ripercorrere ogni passo di ogni vicenda, e tuttavia si ha l’impressione di aver vissuto lo svolgersi della storia di ciascun uomo.

Che tipo di interazione ebbero i prigionieri con la comunità italoamericana?

Dopo l’armistizio italiano del settembre 1943, i POW italiani ebbero la possibilità di unirsi alle Italian Service Units in ruoli non combattenti a supporto dello sforzo bellico statunitense, facendo il bucato, lavorando nei campi, cucinando, ecc. Dovevano prestare giuramento al nuovo governo italiano e venivano trattenuti in campi ISU in vari punti degli Stati Uniti. Il novanta per cento dei prigionieri italiani accettò di servire in queste unità, e alcuni dei lavori che svolgevano permettevano loro maggiori contatti con gli americani. Inoltre, in molti campi ISU, i POW italiani potevano ricevere visite la domenica da famiglie italoamericane locali. A volte veniva loro persino permesso – sempre sotto supervisione – di partecipare a eventi comunitari al di fuori dei campi o di condividere pasti con le famiglie locali. Sbocciarono storie d’amore tra POW e giovani donne italoamericane, alcune delle quali molto serie.

Al contrario, i POW italiani che rifiutavano di collaborare allo sforzo bellico americano venivano mandati in campi in Texas, dove le condizioni erano più severe e le razioni di cibo ridotte. Riuscii a trovare una guardia americana in Texas che era diventata amica dei prigionieri, ma i POW non collaboranti non avevano contatti regolari con le comunità italoamericane.

C’è qualche storia o aneddoto particolarmente interessante che vorrebbe condividere con i nostri lettori?

Mi piacciono tutte le storie, ma quella di Mario e Anna è particolarmente bella. Mario era stato prigioniero a Ogden, appena fuori Salt Lake City, nello Utah. Anna e la sua famiglia andavano a far visita la domenica sperando di trovare prigionieri che potessero conoscere i loro parenti in Italia. Mentre il padre di Anna era scettico riguardo alla storia d’amore, alla fine diede la sua approvazione dopo aver interrogato Mario sulle sue intenzioni in una lunga conversazione in un garage gelido in pieno inverno. Dopo la guerra, Mario fu rimpatriato, ma Anna lo seguì in Italia per sposarlo.

Anna sarebbe anche rimasta in Italia, ma non c’erano abbastanza opportunità di lavoro per Mario, e c’erano serie carenze di cibo. Così, decisero di tornare insieme negli Stati Uniti. Trascorsero il resto della loro vita a Ogden, la città in cui lui aveva servito in una Italian Service Unit. Acquistarono una delle baracche dismesse dei prigionieri e la trasformarono nella loro prima casa.

Un dettaglio toccante che non è entrato nel film è che Anna aveva sempre sognato, da giovane, di trasferirsi sulla costa occidentale. Ma Mario si affezionò profondamente alla sua famiglia, così rimasero a Ogden e lì crebbero i loro tre figli. Non ebbe mai l’occasione di vivere vicino all’oceano, ma costruì una vita piena e felice, circondata dalla famiglia e dai nipoti. Mario chiude il film dicendo: “Nel profondo, ami il tuo Paese (l’Italia), ma l’America mi ha dato tutto.”

Che cosa accadde ai prigionieri alla fine della guerra?

Alla fine della guerra, i POW che servivano nelle Italian Service Units avevano contribuito con milioni di ore allo sforzo bellico, ma nessuno ebbe l’opportunità di rimanere negli Stati Uniti. Nel gennaio 1946 tutti i prigionieri furono rimpatriati, molti lasciando negli USA relazioni importanti con donne italoamericane – nella speranza, ma senza certezza, di riuscire a mantenere un legame.

Per i prigionieri il ritorno in Italia fu uno shock devastante: trovarono un Paese profondamente distrutto dalla guerra. E per i POW che non avevano collaborato con gli Stati Uniti, il rientro comportò anche il confronto con il fatto che molti amici e parenti avevano deciso di sostenere lo sforzo alleato, e quella posizione non collaborante non era più popolare né ufficialmente né socialmente.

Alcune delle coppie che si erano conosciute in America decisero di sposarsi. Per farlo, le donne americane dovettero andare in Italia e sposarsi lì (a causa delle quote che limitavano l’immigrazione negli Stati Uniti). Molto spesso, a causa delle difficoltà economiche in Italia, queste coppie tornarono poi negli USA per crescere le loro famiglie nei luoghi in cui le donne vivevano e dove avevano ancora un lavoro. Non sappiamo quanti ex prigionieri scelsero di tornare a vivere in America, ma diversi tra quelli presenti nel film vissero come cittadini americani proprio nelle città in cui erano stati prigionieri nemici.

Che cosa le ha insegnato questa storia?

Ho imparato molto realizzando il film, ma ci sono due cose che vorrei sottolineare.

La prima è ovvia, ma in qualche modo non ci avevo mai riflettuto davvero prima di fare questo lavoro. La guerra cambia la vita, anche per coloro che non partecipano a battaglie intense, perché interrompe il corso naturale della giovinezza. È stato illuminante capire che adolescenti vengono portati ad addestrarsi come soldati e poi trattenuti per anni in servizio di guerra, privandoli dell’istruzione, delle esperienze lavorative e delle esperienze di vita che avrebbero avuto in quegli anni. Uno dei POW nel film lavorò come manovale per tutta la vita perché non terminò mai la scuola, mentre gli altri fratelli avevano lauree e professioni e vite completamente diverse – un esempio durissimo di come quei giovani soldati non recuperino mai gli anni perduti.

L’altra cosa che ho apprezzato nell’imparare è stata la forza dei legami tra italiani e americani sia prima sia dopo la Seconda guerra mondiale. Molto prima della guerra, c’era già un flusso costante di italiani che veniva negli Stati Uniti per lavorare e poi tornava a casa, quindi il legame tra Italia e Stati Uniti era già ben radicato.

Gli italiani avevano idee chiare sugli Stati Uniti, grazie a chi c’era stato ma anche ai film. Mio zio racconta nel documentario di essere stato catturato in Nord Africa dagli inglesi e di essersi rivolto subito a un amico dicendo: “Andiamo con gli americani: con loro andrà meglio!” Così “scapparono” dai prigionieri britannici per unirsi a quelli americani. In qualche modo, già allora avevano quest’idea degli Stati Uniti ed erano curiosi di sperimentarli.

Sono molto felice di aver avuto l’opportunità di realizzare questo film e offrire una finestra su queste storie – altrimenti destinate a rimanere ai margini della storia.

Potete leggere di più sul film e sul contesto storico sul sito: www.PrisonersInParadise.com