Lou Del Bianco (Author of the book “Out of Rushmore's Shadow: The Luigi Del Bianco Story”)

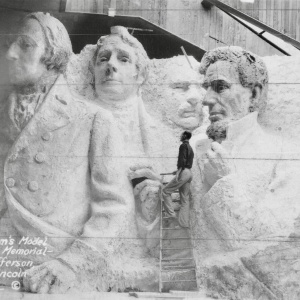

Mount Rushmore: un'impresa impossibile per tutti, tranne che per un italiano in America

I'm not an art critic, I'm not even an expert, but I believe that appreciation and judgment of art is subjective and personal: mine is that the most incredible work of art ever created is Mount Rushmore. For difficulty, danger, accomplishment, talent, inventiveness, precision, vision. Can you imagine what it's like to sculpt a mountain hanging in the air at 500 feet from the ground, exposed to the elements, without being able to control in real time the result of your work, with a very heavy and not at all precision instrument, making it become a face? And not just any face, one known to all!

And what origins could the chief carver of this work of art have, who physically made a part of it and taught others how to do it? Of course he was Italian, his name was Luigi Del Bianco. His contribution to an icon of the United States is a symbol of how much Italians, whether born here or already born in America, have done to the beauty that there is in the United States, to its greatness, to its symbols. Today we host Lou Del Bianco, grandson of that visionary artist from Friuli Venezia Giulia and author of the book “Out of Rushmore's Shadow: The Luigi Del Bianco Story”. It's a great way to start this hopeful 2021.

Lou, please tell us the story of Luigi Del Bianco before Mount Rushmore

My nonno was born in 1892 in what was called Borgo Del Bianco, in the town of Meduna, in the province of Pordenone, in the Region of Friuli Venezia Giulia.

When he was about 12 or 13 years old, he carved a little dog out of the wood. My great grandfather, Vincenzo Del Bianco, sent him to Austria because that’s where the nearest carving school was. So my grandfather studied 3 years under an Italian Master in Austria and then he came back to Italy and studied in Venice for 2 years.

In 1910 he wrote a postcard to his relatives in the US to work for as a memorial stone carver in Barre, VT. His cousin, Pietro Del Bianco, sponsored my grandfather who came to America and worked in a stone quarry for five years. When Italy got involved in WWI against Prussia, he went back to Italy and fought with the Italian Army.

In 1920 he came back to Barre where he met a fellow stone carver named Alfonso Scafa who brought my grandfather to Stamford, CT to meet Gutzon Borglum, the designer of Mount Rushmore. Borglum hired him as expert in granite and then as head stone carver. My grandfather settled in Port Chester, New York, which was only fifteen minutes away from Connecticut and where Scafa introduced him to my grandmother Nicoletta Cardarelli.

In 1933, Gutzon Borglum was already heading the carving of Mount Rushmore when he realized that the men carving under him could block out the faces but he needed a granite stone carver who could refine the faces. That’s why he called my grandfather, who became the chief carver of Mount Rushmore.

Please tell, us about this wonderful adventure, Mount Rushmore

In 1925, Doane Robinson, the historian of South Dakota (where Mount Rushmore is located) wanted to bring tourists there. So he came up with the idea to add some sculptures of important people of the story of the West, and to do that, he approached Gutzon Borglum. Borglum said that these sculptures should be in the side of a mountain and the figures should be Presidents.

Gutzon Borglum decided for Washington because he was our first president, Jefferson because he extended our country and Theodore Roosevelt because he wanted to preserve National forests and parks. He picked Lincoln because he literally saved our democracy. So, Mount Rushmore became known as “The Shrine of Democracy”.

Most of the men who worked there were coal and silver miners, and they had no experience in art and carving. Borglum needed men that were not scared of going 500 feet up in the air so he thought that if he hired these unemployed miners, and if he trained them to follow his instructions, he would have been able to accomplish his mission using these men.

But he also needed other trained men. My grandfather was chosen because Borglum knew that he would have been able not only to refine the faces, but he could also train the rest of the team. My grandfather worked with Ugo Villa, who was Borglum’s chief pointer (in charge of transferring measurements from the model to the finished piece). Since Borglum was often going to Washington to look for some money for the project, when he was not there, Villa was in charge of the project. But, because of disagreements on how to carve the difficult stone, Borglum fired him and replaced him with my grandfather.

Used to have technology in the palm of our hands, I don’t think that we can actually realize how incredible was the work on this piece of art. Please help our readers realize in which conditions was Mount Rushmore actually carved

My grandfather would work 500 feet in the air in a scaffold. He would have the sun on the back of his head, the wind would make the scaffold move and his face was white like a ghost because of the dust. Furthermore, the drill they were using weighed 40 pounds. So, you had to be physically strong, very brave and very talented: and my grandfather had all these characteristics.

My grandfather was interviewed in 1967 by a local newspaper and he talked about the fact that while he was carving close up on a giant granite face, his work would have to look perfectly proportionate from a mile away.

There are just two others works comparable to it and one was actually started by Gutzon Borglum: it’s called Stone Mountain. It is a relief, so not as demanding as Mount Rushmore, of the confederal leaders of the Civil war in the South: nowadays it is very controversial. Borglum used some of the technique adopted in the Stone Mountain to build Mont Rushmore. There is also a gigantic mountain’s sculpture of the Native American hero called Crazy Horse, which was started in 1940s by Korczak Ziolkowski. He was hired by Borglum after my grandfather decided to leave Mont Rushmore because of the way he was treated. At a certain point, Ziolkowski argued with Borglum, they had a fight, he stopped working for Borglum and he said that he would take revenge carving his own mountain sculpture with the aim of putting Mount Rushmore to shame. This mountain’s sculpture is still a work in progress. Even today they have a lot of technological devices, they are still using some of Mount Rushmore’s techniques.

Is there an anecdote, a funny story about this incredible endeavor your grandfather realized?

When my grandfather arrived at Mount Rushmore, there were no places where he could get Italian food. So he put some of it in the backseat of his car and he offered it to the Natives: they loved it. At the beginning, my grandfather had problems in socializing with the Americans working on the Mountain. They all drank whiskey but he drunk wine. He was an immigrant and he spoke broken English. But, thanks to Italian food, he became a friend of the Native Americans in South Dakota, who also taught him how to ride a horse. Furthermore, my grandmother cooked maccheroni and sauce for the workers and taught their wives how to cook it.

I know something about your struggle to see your grandfather's work recognized. Will you tell it to our readers, please?

In 1985 the most definitive book about Mount Rushmore was written: my uncle read it but he realized that Luigi, his father, was not mentioned. How could they not even mention the chief carver? We were so angry about that! Me and my uncle wanted to find out the truth once and for all because my grandfather didn’t talk about it very often.

In 1988 I went to Mount Rushmore and asked how they were honoring the chief carver. They showed me this plaque about all the 400 men who worked for Mount Rushmore: my grandfather was in a sea of names. We found that unfair; we wanted him to have his own plaque.

We went to the Library of Congress in Washington DC, looking for all the papers of Gutzon Borglum. My uncle found out that the people in charge of the Rushmore project complained a lot about him. Borglum had to constantly defend my grandfather saying that he was “…worth any three men in America for this particular kind of work…” We didn’t understand the reason of such hate, we suppose it was related to the fact that he was Italian: but it was especially this characteristic that made him so essential for the work. In 1937, my grandfather decided he had enough and he left Mont Rushmore. But, in 1940 Borglum wrote to him saying that he had to come back to finish Mount Rushmore under the promise that no one would bother him. So, for six months, he worked alone on the faces.

My uncle and I took all the documents that Borglum wrote and we presented them to the staff at Mount Rushmore, showing that my grandfather should be recognized as chief carver. Despite that, they replied to us that he was a worker just like the others: and this was what I was told for over 25 years.

When my uncle Cesar got ill, before he passed away, he asked me to put an end to all of this. And then, in 2015, Cam Sholley replaced the head of all the national parks in the midwest region of the USA. After failing to convince so many officials before him, I tried pitching to Cam my request. He told me he would send two historians to my house in Port Chester to reanalyze the case and the documents I had. They finally decided to recognize Luigi Del Bianco and now he has his own plaque where he is acknowledged as chief carver.

Is it correct to say that no one more than Luigi Del Bianco represents and symbolizes the fantastic manual skill of the millions of Italian immigrants who have literally built and embellished America?

Luigi Del Bianco and so many other Italian stone carvers never got credit for the beautiful things they created. There were many other Italian immigrants who did incredible architecture or carvings and they remained unknown: the only ones who are known are the Piccirilli brothers. They did incredible beauties and I have no proof that they met my grandfather, but they lived very close, so I’m quite sure they did. I’d like to think that my grandfather represents all the anonymous Italian artisans who had never been credited for the beauty they created in America.

Does Italy, in any way, recognize or remember Luigi Del Bianco? How can we help?

Actually, I was thrilled by the attention Italy gave to my grandfather, especially the people from Pordenone who published my book in Italian and put a plaque in Borgo Del Bianco. Furthermore, an Rai television show called “Voyager” came to my house, interviewed me and made a whole segment about my grandfather’s story.

I do not have a lot of memories about my grandparent. But, as a little 6 year old boy, I remember my grandfather saying “’I’m Luigi, you are Luigi”. I was his only grandson so there was a profound bond we shared. I felt like he charging me with something to do for him. When I found out that he was chief carver, I was in second grade and he had already passed away: so I’ve been looking for him in that mountain for my whole life.

The essence of all of this to me is that history doesn’t always tell you the whole story, you have to find the truth yourself, and I’m happy because I found out the truth for someone that I loved.

I'm not an art critic, I'm not even an expert, but I believe that appreciation and judgment of art is subjective and personal: mine is that the most incredible work of art ever created is Mount Rushmore. For difficulty, danger, accomplishment, talent, inventiveness, precision, vision. Can you imagine what it's like to sculpt a mountain hanging in the air at 500 feet from the ground, exposed to the elements, without being able to control in real time the result of your work, with a very heavy and not at all precision instrument, making it become a face? And not just any face, one known to all!

And what origins could the chief carver of this work of art have, who physically made a part of it and taught others how to do it? Of course he was Italian, his name was Luigi Del Bianco. His contribution to an icon of the United States is a symbol of how much Italians, whether born here or already born in America, have done to the beauty that there is in the United States, to its greatness, to its symbols. Today we host Lou Del Bianco, grandson of that visionary artist from Friuli Venezia Giulia. It's a great way to start this hopeful 2021.

Lou, please tell us the story of Luigi Del Bianco before Mount Rushmore

My nonno was born in 1892 in what was called Borgo Del Bianco, in the town of Meduna, in the province of Pordenone, in the Region of Friuli Venezia Giulia.

When he was about 12 or 13 years old, he carved a little dog out of the wood. My great grandfather, Vincenzo Del Bianco, sent him to Austria because that’s where the nearest carving school was. So my grandfather studied 3 years under an Italian Master in Austria and then he came back to Italy and studied in Venice for 2 years.

In 1910 he wrote a postcard to his relatives in the US to work for as a memorial stone carver in Barre, VT. His cousin, Pietro Del Bianco, sponsored my grandfather who came to America and worked in a stone quarry for five years. When Italy got involved in WWI against Prussia, he went back to Italy and fought with the Italian Army.

In 1920 he came back to Barre where he met a fellow stone carver named Alfonso Scafa who brought my grandfather to Stamford, CT to meet Gutzon Borglum, the designer of Mount Rushmore. Borglum hired him as expert in granite and then as head stone carver. My grandfather settled in Port Chester, New York, which was only fifteen minutes away from Connecticut and where Scafa introduced him to my grandmother Nicoletta Cardarelli.

In 1933, Gutzon Borglum was already heading the carving of Mount Rushmore when he realized that the men carving under him could block out the faces but he needed a granite stone carver who could refine the faces. That’s why he called my grandfather, who became the chief carver of Mount Rushmore.

Please tell, us about this wonderful adventure, Mount Rushmore

In 1925, Doane Robinson, the historian of South Dakota (where Mount Rushmore is located) wanted to bring tourists there. So he came up with the idea to add some sculptures of important people of the story of the West, and to do that, he approached Gutzon Borglum. Borglum said that these sculptures should be in the side of a mountain and the figures should be Presidents.

Gutzon Borglum decided for Washington because he was our first president, Jefferson because he extended our country and Theodore Roosevelt because he wanted to preserve National forests and parks. He picked Lincoln because he literally saved our democracy. So, Mount Rushmore became known as “The Shrine of Democracy”.

Most of the men who worked there were coal and silver miners, and they had no experience in art and carving. Borglum needed men that were not scared of going 500 feet up in the air so he thought that if he hired these unemployed miners, and if he trained them to follow his instructions, he would have been able to accomplish his mission using these men.

But he also needed other trained men. My grandfather was chosen because Borglum knew that he would have been able not only to refine the faces, but he could also train the rest of the team. My grandfather worked with Ugo Villa, who was Borglum’s chief pointer (in charge of transferring measurements from the model to the finished piece). Since Borglum was often going to Washington to look for some money for the project, when he was not there, Villa was in charge of the project. But, because of disagreements on how to carve the difficult stone, Borglum fired him and replaced him with my grandfather.

Used to have technology in the palm of our hands, I don’t think that we can actually realize how incredible was the work on this piece of art. Please help our readers realize in which conditions was Mount Rushmore actually carved

My grandfather would work 500 feet in the air in a scaffold. He would have the sun on the back of his head, the wind would make the scaffold move and his face was white like a ghost because of the dust. Furthermore, the drill they were using weighed 40 pounds. So, you had to be physically strong, very brave and very talented: and my grandfather had all these characteristics.

My grandfather was interviewed in 1967 by a local newspaper and he talked about the fact that while he was carving close up on a giant granite face, his work would have to look perfectly proportionate from a mile away.

There are just two others works comparable to it and one was actually started by Gutzon Borglum: it’s called Stone Mountain. It is a relief, so not as demanding as Mount Rushmore, of the confederal leaders of the Civil war in the South: nowadays it is very controversial. Borglum used some of the technique adopted in the Stone Mountain to build Mont Rushmore. There is also a gigantic mountain’s sculpture of the Native American hero called Crazy Horse, which was started in 1940s by Korczak Ziolkowski. He was hired by Borglum after my grandfather decided to leave Mont Rushmore because of the way he was treated. At a certain point, Ziolkowski argued with Borglum, they had a fight, he stopped working for Borglum and he said that he would take revenge carving his own mountain sculpture with the aim of putting Mount Rushmore to shame. This mountain’s sculpture is still a work in progress. Even today they have a lot of technological devices, they are still using some of Mount Rushmore’s techniques.

Is there an anecdote, a funny story about this incredible endeavor your grandfather realized?

When my grandfather arrived at Mount Rushmore, there were no places where he could get Italian food. So he put some of it in the backseat of his car and he offered it to the Natives: they loved it. At the beginning, my grandfather had problems in socializing with the Americans working on the Mountain. They all drank whiskey but he drunk wine. He was an immigrant and he spoke broken English. But, thanks to Italian food, he became a friend of the Native Americans in South Dakota, who also taught him how to ride a horse. Furthermore, my grandmother cooked maccheroni and sauce for the workers and taught their wives how to cook it.

I know something about your struggle to see your grandfather's work recognized. Will you tell it to our readers, please?

In 1985 the most definitive book about Mount Rushmore was written: my uncle read it but he realized that Luigi, his father, was not mentioned. How could they not even mention the chief carver? We were so angry about that! Me and my uncle wanted to find out the truth once and for all because my grandfather didn’t talk about it very often.

In 1988 I went to Mount Rushmore and asked how they were honoring the chief carver. They showed me this plaque about all the 400 men who worked for Mount Rushmore: my grandfather was in a sea of names. We found that unfair; we wanted him to have his own plaque.

We went to the Library of Congress in Washington DC, looking for all the papers of Gutzon Borglum. My uncle found out that the people in charge of the Rushmore project complained a lot about him. Borglum had to constantly defend my grandfather saying that he was “…worth any three men in America for this particular kind of work…” We didn’t understand the reason of such hate, we suppose it was related to the fact that he was Italian: but it was especially this characteristic that made him so essential for the work. In 1937, my grandfather decided he had enough and he left Mont Rushmore. But, in 1940 Borglum wrote to him saying that he had to come back to finish Mount Rushmore under the promise that no one would bother him. So, for six months, he worked alone on the faces.

My uncle and I took all the documents that Borglum wrote and we presented them to the staff at Mount Rushmore, showing that my grandfather should be recognized as chief carver. Despite that, they replied to us that he was a worker just like the others: and this was what I was told for over 25 years.

When my uncle Cesar got ill, before he passed away, he asked me to put an end to all of this. And then, in 2015, Cam Sholley replaced the head of all the national parks in the midwest region of the USA. After failing to convince so many officials before him, I tried pitching to Cam my request. He told me he would send two historians to my house in Port Chester to reanalyze the case and the documents I had. They finally decided to recognize Luigi Del Bianco and now he has his own plaque where he is acknowledged as chief carver.

Is it correct to say that no one more than Luigi Del Bianco represents and symbolizes the fantastic manual skill of the millions of Italian immigrants who have literally built and embellished America?

Luigi Del Bianco and so many other Italian stone carvers never got credit for the beautiful things they created. There were many other Italian immigrants who did incredible architecture or carvings and they remained unknown: the only ones who are known are the Piccirilli brothers. They did incredible beauties and I have no proof that they met my grandfather, but they lived very close, so I’m quite sure they did. I’d like to think that my grandfather represents all the anonymous Italian artisans who had never been credited for the beauty they created in America.

Does Italy, in any way, recognize or remember Luigi Del Bianco? How can we help?

Actually, I was thrilled by the attention Italy gave to my grandfather, especially the people from Pordenone who published my book in Italian and put a plaque in Borgo Del Bianco. Furthermore, an Rai television show called “Voyager” came to my house, interviewed me and made a whole segment about my grandfather’s story.

I do not have a lot of memories about my grandparent. But, as a little 6 year old boy, I remember my grandfather saying “’I’m Luigi, you are Luigi”. I was his only grandson so there was a profound bond we shared. I felt like he charging me with something to do for him. When I found out that he was chief carver, I was in second grade and he had already passed away: so I’ve been looking for him in that mountain for my whole life.

The essence of all of this to me is that history doesn’t always tell you the whole story, you have to find the truth yourself, and I’m happy because I found out the truth for someone that I loved.

You may be interested

-

“The Hill” St. Louis’ Little Italy

When the fire hydrants begin to look like Italian flags with green, red and white stripes,...

-

An Unlikely Union: The love-hate story of Ne...

Award-winning author and Brooklynite Paul Moses is back with a historic yet dazzling sto...

-

Cathedral of St. John the Divine, Oratorio S...

For the first time ever, The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, in collaboration with the O...

-

Davide Gambino è il miglior "Young Italian F...

Si intitola Pietra Pesante, ed è il miglior giovane documentario italiano, a detta della N...

-

Garibaldi-Meucci Museum to Celebrate Ezio Pi...

On Sunday, November 17 at 2 p.m., Nick Dowen will present an hour-long program on the life...

-

Holiday Concert with Micheal Castaldo and Ma...

The Mattatuck Museum (144 West Main St. Waterbury, CT 06702) is pleased to celebrate...

-

Italian American Culture Night

Tuesday, April 14 - 6.30 pm EDTSt. James Church Rocky Hill - 767 Elm St, Rocky Hill,...

-

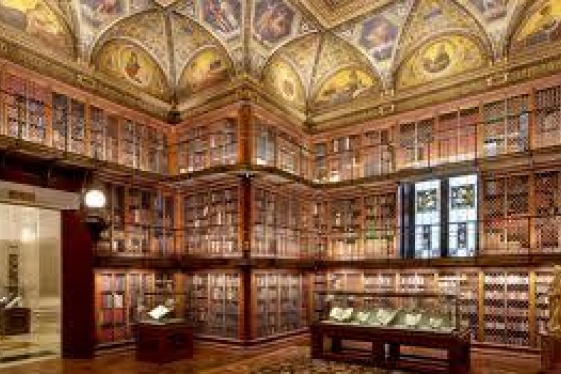

Italian Master Drawings From The Morgan (Onl...

The Morgan Library & Museum's collection of Italian old master drawings is one of the...