WTI Magazine #12 2014 Jan, 10

Author : Enrico De Iulis Translation by: Alessandra Bitetti

Massimo Campigli is the pen name of Max Ihlenfeldt. He was born in 1895 in Germany, but he moved to Florence with his mother and his grandmother. The relationship between them was particularly incisive in the life and psychology of Max, who - until the age of fifteen - believed to be the son of his grandmother and the grandson of the woman that was actually his mother.

From an early age he dealt with journalism in Milan, where his mother moved with her new husband. But then, with the First World War, Campigli voluntarily enlisted in the infantry, having already submitted his application to obtain the Italian citizenship.

At those time he also made his first approach to art and specifically to the Futurist Milanese tendency, from which he then separated.

The history of Italian Art of that period has many representatives that were deployed in first person in political and military activism and in reality, Futurism is a sort of brief result of this double meaning of the artists/soldiers. The painter Umberto Boccioni and the architect Antonio Sant'Elia, both futurists, were in fact killed during the First World War.

In 1919, after many vicissitudes, Campigli managed to come back to Italy and to his old job as journalist, but this time he became a news correspondent for the daily "Corriere della Sera", from Paris. The period was rather troubled, because he had to combine his work as a journalist with his work as a painter, and because he had to support his family that in the meantime came back to Florence.

From 1921 he succeed in making his first exhibit and won his first awards, but his career had a turning point only after 1927, when he visited (and remained deeply impressed by) the Museum of Etruscan Art of Villa Giulia in Rome.

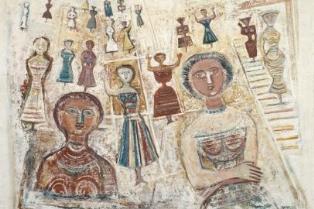

Suddenly his art changed direction toward a more primitive style and he started making a reported engraving on canvas, an hardened of graphic elements, such as scratched on a hard material; the figures became geometrical and elementary as prehistoric, but full of culture and aesthetics of everyday life. A sort of graffiti on the modern life of the '20s.

Not surprisingly, the characters are almost always women: women that are fixed in their figures, stable, but graceful and sometime ethereal while remaining very "rock", never mawkish.

It was a personal style, but it managed to be a very integrated branch with almost the whole Italian movement called "Novecento", which was a tree with many branches but had its roots in the primitive geometry and the taste of the graffiti and the engraved sign. Not surprisingly, this kind of style will find its approval in the bourgeois culture, and it will occupy not only painting, but also the minor arts such as ceramics, porcelain and glass reaching almost every day the taste of the Italian people.

The figure of Campigli will be resumed in the decoration of palaces halls, ceramic plaques, lamps, vases and furnishings: it will be one of the first cases of trend setting itself, where by the onset of pure artistic style, it will lead to the spread of bourgeois fashion in the every day life.

The production of Campigli will continue until 1971 - the year of his death - remaining very coherent with his figurative culture that originated from its origins: the Etruscans, women, graphic personality, and Parisian fashion dictating the taste of the 40s, in spite of his will.