It is impossible, if not even pretentious, to accurately illustrate what is happening during the Holy Week in two regions rich in popular traditions such as Basilicata and Puglia. The religious practices of the Lenten and Easter cycle, present almost everywhere, are very varied and articulated, even though they present devotional and scenic-representative behaviours very similar to the other regions of Central and Southern Italy.

Variants and similarities are expressions of community and socio-cultural experiences that define the historical and anthropological substratum of the context that has shaped them, in which they continue to make sense. However, each and all of the actions of these "feasts of pain", as the representations and penitential practices are felt by the people, have such characteristics that, if not unique, they are always of particular importance.

The two different dimensions - the popular, extra and paraliturgical one; and the cultured, liturgical and religious one - are everywhere merged into a single and organic ceremonial body. The result is a strong mystical value in which each individual, believing or not, can be emotionally involved or be surprised by the participation that entire communities fully express. Each performance presents forms of devotion in which the private and the public, the individual and the collective, the protagonist and the spectator form a participatory unit that makes each ritual act fully meaningful, even in the different ceremonial expressions.

For some decades now, these pain festivals have been seen as an identity emblem with which local realities, through the manifestation of their own religious emotion, present themselves to the eyes of those who follow the celebration, recalled by the dynamics of tourism and cultural consumption.

For Puglia, the book by Francesco Di Palo "Stabat Mater Dolorosa" is fundamental for documentary richness and contribution of analysis; for Basilicata there is no equivalent work. Here I will recall a few examples of the many Holy Weeks celebrated in the two regions, limiting myself to the most well-known and user-friendly ones.

The procession of the Addolorata in San Marco in Lamis (Foggia) takes place at dawn on Good Friday. When the "Stabat Mater" sing begins, the statue of Our Lady is led on a visit to the "sepulchres" set up in the churches of the town, similarly to what happens in many other Apulian and Lucanian centres.

In San Mauro Forte (Matera) the statue of Our Lady of Sorrows is effortlessly brought from church to church all night long by women in widow's weeds who, at every stop in front of the "sepulchres", sing in dialect the cry of Mary.

The second procession of San Marco in Lamis takes place in the afternoon and is characterized by the presence of the "Fracchie": giant torches obtained by opening an entire tree so that it takes the form of a cone filled with several quintals of wood; the remaining section of the integral trunk is fixed on an axis with two wheels. Once on fire, the fracchie burn until late at night. Initially they were simple torches by hand, made with devotion and used to illuminate the path of the evening procession with the statue of the Addolorata. The survivors of the First World War, as a sign of thanksgiving, began to build bigger and bigger fracchie. Today some, at the dimeter of the base of the cone, measure over two and a half meters. One of the most emotional and spectacular moments is the scene of the encounter between the statue of the Madonna, brought by the women dressed in mourning, and that of Christ.

In Bisceglie and San Severo the two statues have real hair, collected from votive offerings. The two processions meet and, once in contact, the statues are close to simulate the mother's kissing of her son. The spectacularization, which connects living characters with statues reproducing scenes of the Passion, touches levels of strong emotional involvement.

In Alberona (Foggia) the crucifixion is realized with the statue of Jesus with articulated arms. The same emotional tension for the strong realism of the scene is re-proposed in the moment of the deposition, when the arms of Christ fall hanging along the body. I saw similar statues in Irpinia, and also in Mexico, where the hair on the statue of Jesus is laid down by girls after their first menstruation. The images treated as living people create the fusion of the statues with the characters in flesh and blood; this fusion between reality and verisimilitude makes humans and statues protagonists of the scenes in which one and the other, indiscriminately, seem to belong to the same mystical dimension.

Almost everywhere we find the processions of the Mysteries, which take place from Thursday to Holy Saturday, with groups of statues in wood or in Papier-mâché from Lecce, some of interesting historical and artistic value, representing various episodes of the passion of Christ. Entire scenes with many characters almost life-size are represented in the procession of Valenzano, as, for example, in the sculptural group of the Last Supper, of the Cyrene, of the Crucifixion and of the Deposition. Often the statuary groups, carried on the shoulder by members of the confraternities or by those who sometimes keep them even in their own homes, are preceded by figures that bear the various symbols of the Passion.

In some of these processions there are bearers of crosses, hooded, barefoot and with chains tied to the ankles. In Troia (Foggia), for example, hooded people dress with white tunics; in Francavilla Fontana (Brindisi) the bearers of large crosses dress up in flaming red. Particularly interesting, due to the strong suggestion and intensity of penitential participation, is the procession of crucifers (called via cruci) of Noicattaro (Bari) which takes place without stopping from Friday to Saturday. On the evening of Friday, several dozens of via cruci, penitents whose identity is unknown, carry heavy crosses even a few dozen kilos. They mostly come from other towns and also from abroad; they dress a black sack, they are hooded, with their heads surrounded by crowns of thorns or vine branches; they drag, barefoot, a heavy chain tied to the ankle. Numerous participants take part in the processions of the Sorrows, of the Mysteries and of the Dead Christ placed in the naca (catafalque). Women are all in black and men, in formal dress, bear the statues on their shoulders. The via cruci, once they reach the church, dissolve the chain and the they begin a self-flagellation, now only in symbolic form. To the bearers of crosses are added hooded penitents who, participating in processions, or in isolation, proceed very slowly to visit the sepulchres.

With different denominations, there are also pairs of penitents who, in white twill and hood, barefoot, with crowns of thorns or vine branches on their heads, with a stick that beats rhythmically on the ground, visit the sepulchres. They are present in the processions in Francavilla Fontana in the province of Brindisi (called pappamusci), Mottola (paranze) and Grottaglie (bublibubli), both in the province of Taranto. To these are added the heavy crucified bearers, who participate in the various processions of the Mysteries, of the Sorrows and of the Dead Christ, all accompanied by the jarring of torches and litanies of the various confraternities. The penitents of Taranto, called Perdune, are very well known and actors of a more articulated ceremonial. On the hood they have a black dome hat with a large dome and wide flap, on the chest there is a "dwelling" on which Decor Carmeli is written; they have a stick with which they hit the ground, they go on pilgrimage to the sepulchres with short steps and continuously swinging. As for how the ceremony is brough on, the celebration of Holy Week in Taranto is certainly among the most complex and suggestive, being an expression of strong devotional and tourist attraction.

In Basilicata the representations of Holy Week and the presentation of the Mysteries are mostly made with living characters. The towns where the representations are the oldest, articulated and varied, are at the foot of Monte Vulture: Barile and Ginestra, of Albanian origin, and Rionero in Vulture and Atella.

Other representations of Holy Week, with living characters are staged almost everywhere in the rest of the region, similar to that of Barile, by now of great tourist attraction. The processions of the Mysteries are also widespread everywhere with sacred images are accompanied by characters bearing all the symbols of the Passion. All of them have strong tension and emotional and spectacular participation: let me remember those of Venosa (Potenza) and Pisticci (Matera), in all similar to the many other active in the rest of the region, increasingly and better organized by local Pro-Loco and cultural associations.

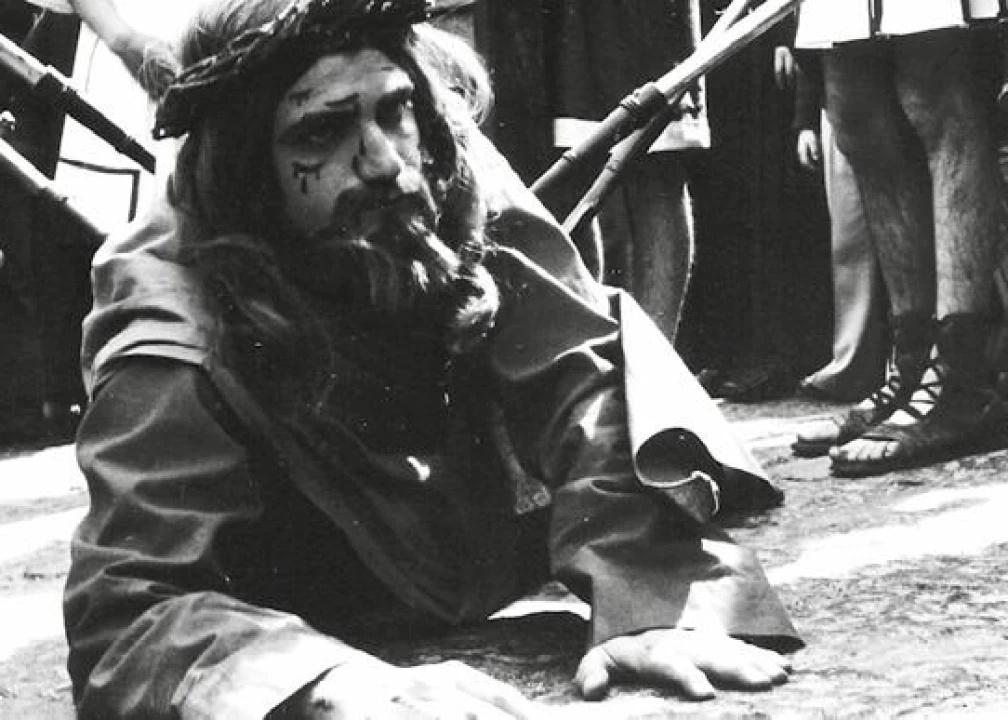

Of particular anthropological interest, moreover, is the chant of the Passion of Tricarico. It is a singular oral tradition: in some of its parts is described the pursuit of Christ who, to evade the soldiers is hidden in a cave that closes with a spider web: an episode that recalls a passage of the Egira in which the same story is lived by Mohammed. For some decades a representation of the Passion, with living characters, has been staged in the Sassi di Matera where the ancient districts make the scene more likely, especially after "The Gospel according to Matthew" by Pier Paolo Pasolini and "The Passion of Christ" by Mel Gibson.

From a demo-anthropological point of view, the representation of Barile is perhaps the most interesting, for the large number of characters and for the preparation that the main ones must undergo with days of penitential isolation and spiritual preparation. The role of Christ and Our Lady is entrusted to a couple of boyfriends whose moral level is recognized and who must marry in the year. The entire community and the urban structure are involved in the representation that includes pathways and stops, for the process and other collective actions, in various squares and streets.

In these representations, an important character is that of the Gypsy: a beautiful and enchanting girl who distributes lupin beans and sweets to the public. A disturbing character who, according to the popular legend, provided the nails of the crucifixion. Other disturbing characters are present in the representation of Vulture: two boys dressed in wild clothes during the procession, of which they are part, play ball.

The symbols of the Passion are also displayed in these processional scenes, particularly by women and girls. In Barile, three girls on white cruciferous angel dresses sew all the jewels that the community was deprived of during Holy Week. In Rionero and Atella, also in the province of Potenza, the representation ends with the crucifixion: Christ and the thieves, young people of the place, are linked to the crosses, while in the square another young man, in the role of Judah, simulates the hanging. Shortly after that, in Atella, Christ, in the figure of a living person, is laid in a cave that acts as a sepulchre, where the devotees visit.

By Vincenzo Spera for "Il folklore d'Italia"