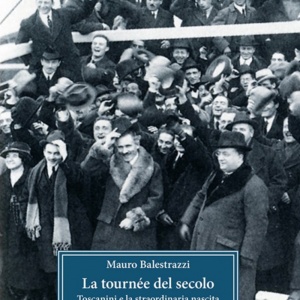

Mauro Balestrazzi (Author of the book “La tournée del secolo”)

Toscanini in America: La tournée del secolo

In the list of the great Italian excellences who have found their fortune in America, one of the highest level names is that of Arturo Toscanini. A century has passed since an extraordinary event, an exceptional tour that saw him as a protagonist in America together with what would later become the orchestra of La Scala in Milan.

Today there is a book, “La tournée del secolo”, that describes this historic musical event, a perfect metaphor for the wonderful encounter between Italy and the United States, which has always been the subject of these interviews. We welcome the author, Mauro Balestrazzi, whom we thank for his courtesy and great knowledge of this beautiful Italian story in America.

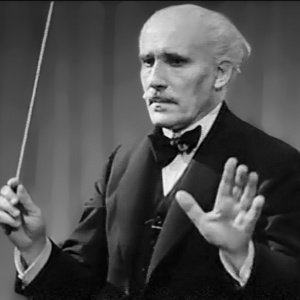

Mauro, we ask you to begin by explaining to our readers the greatness of Arturo Toscanini and his importance for the history of music.

Toscanini made his debut as conductor at 19 in Brazil. Already as a student he had revealed an exceptional musical talent, so much so that his classmates in the Conservatory considered him a genius and so they called him, “géni”, in Parmesan dialect. As soon as he graduated, he had been hired by an opera company: it was 1886 and at that time it was common for Italian orchestras and singers to journey to perform in South America, where there were many of our compatriots and the passion for opera was widespread.

Toscanini, who had been hired as first cello, knew the operas by heart and helped the singers review their parts: everyone in the company knew it. One evening in Rio de Janeiro the Aida was scheduled: the titular conductor, a Brazilian, had been contested by the orchestra and singers and then resigned. Instead of him, the substitute maestro, who was rejected by the public out of solidarity with their compatriot, would have had to conduct.

At that point, in a situation of great emergency, there was the risk that not only the evening would be lost, but also the entire tour would be compromised. So a choir from Parma begged the young cellist in dialect: "Ch'al vaga su lu, Toscanén" ("You go on, Toscanini"), hoping that he could save the show and the season. Toscanini was very shy, and he was pushed a little by force onto the podium. He knew Aida by heart and didn't even have to open the score. For the audience it was a real shock to see this young man arrive on stage, and they were so taken aback that they didn't even have the strength to react. In the end Toscanini conducted very well, the evening ended in his personal triumph and he was entrusted with all the other operas of the season.

Already from this debut one can understand the exceptional nature of his artistic personality. At that moment the figure of the orchestra conductor had just been defined, because in the first half of the nineteenth century there was still a maestro who concerted the opera, and therefore prepared the orchestra and the singers for rehearsals, but then it was the first violin that during the performance who dictated the timing of the music: the figure of the sole conductor was imposed only shortly before Toscanini's career began.

His importance was immediately revealed at the end of the century and in the early years of the twentieth century. It can be said that Toscanini changed the way of performing opera and also listening to it. He changed the way of performing it because he decisively opposed the arbiters then customary in the performances and of which even Verdi, a few years earlier, had complained: with the complacency of many conductors, the singers took every liberty, they changed the tempos, they added unwritten high notes. As for the orchestras, they were often improvised and with little preparation. Even though he was still very young, Toscanini imposed on both singers and musicians a discipline that was previously completely unknown. And then he affirmed the figure of the orchestra director as solely responsible for the whole production, not only for the musical part but also for the visual one. He caused a sensation when, in a play in a provincial city, because in his early years he conducted in minor theaters, he forced all the members of the choir to change their shoes because they clashed with the sets and costumes.

I was saying that he also transformed the way of listening to opera because it was he who introduced some reforms in the theater such as that of the darkness in the hall during performances. Today for us it is a foregone conclusion, but then it was not. In the audience, the ladies could keep their hats on their heads, thus blocking the view of those who sat behind them. Toscanini imposed on the public respect for the work of art and created the figure of the modern conductor.

Coming to his artistic career, Toscanini marked the most memorable seasons of the Teatro alla Scala, but he worked for many years in the United States: from 1908 to 1915 at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, then from 1925 to 1936 he directed the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and then the NBC Symphony, an orchestra that was created especially for him in 1937. The radio broadcast his NBC concerts to every corner of America and an American weekly wrote at the time that Toscanini was as popular as Joe DiMaggio, the ace of baseball.

We then must not forget the role that Toscanini also had outside theaters or concert halls, his civil and political commitment in difficult years. When the First World War broke out, Toscanini, who was the son of a Garibaldian and had inherited a very strong patriotic sentiment from his father, actively engaged in conducting concerts and operas for charity. Memorable was the concert at the Milan Arena, in front of forty thousand spectators, to raise funds for the wounded and victims of the war. His commitment took on even stronger connotations during the Fascist period, with his opposition to the regime and Nazism, the solidarity shown concretely to the Jews who were persecuted in Europe, when he went to conduct the newborn Palestine Orchestra, that which would later become the Israel Philharmonic. All these facets of his personality, in addition of course to the great prestige of the musician, contributed to creating what has become a myth.

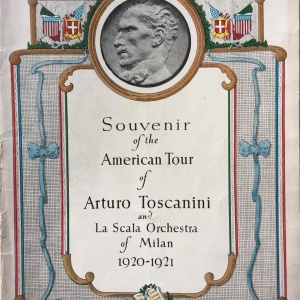

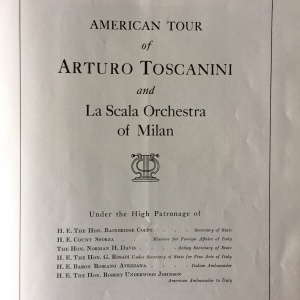

The tour takes place between October 1920 and June 1921. There are 125 concerts in 68 cities in Italy, the United States and Canada...

At the heart of my book is the story of this tour, of which we have just celebrated a century, an undertaking that for its numbers is something truly incredible.

This tour is born and is part of the reconstruction project of the Teatro alla Scala of which Toscanini was the inspiration in the years following the First World War. The refoundation of the theater and its transformation into an autonomous body, therefore with its own management and artistic programming autonomy, was the starting point: the tour was to represent the testing of the orchestra that would later become the permanent orchestra of the Teatro alla Scala. The operation of the refoundation of La Scala was an operation of enormous importance, carried out by the Mayor of Milan with the collaboration of Corriere della Sera, which supported the initiative and also helped to find sponsors for the work. Apart from the hall with the stalls and the boxes, which remained as it was, from the stage to the warehouse for the scenery to the dressing rooms and electrical systems, everything was rebuilt with more modern criteria. The foundations were reinforced and the roof was raised. So there was both an administrative refoundation and a building restructuring of the theater.

Toscanini, as has been said, had been the inspirer of these innovations: he had returned from America when Italy entered the war, and had been asked to take care of La Scala, but he had replied that La Scala had aged, it looked like a museum and needed to be profoundly renovated. Only under these conditions would he undertake to direct it again. As part of this restructuring, which would then lead to the reopening of the theater in December 1921 after a 5-year closure, although in 1918 there had been a short opera season, Toscanini was commissioned to form the new permanent orchestra. Here we start talking about the tour and the Americans, who had greeted with disappointment the departure of Toscanini from the Metropolitan in 1915, enter the scene,

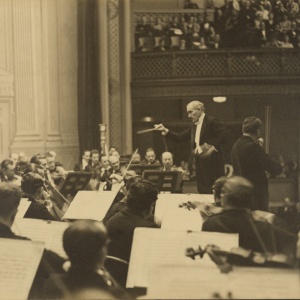

Of course, the Metropolitan had already been a great theater for some time, but with the arrival of Toscanini in 1908 the artistic level had made a huge leap in quality. After his return to Italy, offers continued to arrive from America to return, from theaters but also from symphony orchestras. When Toscanini was commissioned to form the orchestra for La Scala, a group of sponsors was formed in New York ready to finance the tour. This offer also fulfilled two wishes of Toscanini: that of being able to conduct an orchestra shaped by him, with musicians chosen personally and therefore at the level of his artistic needs; and that of returning to the United States and showing his qualities also as a conductor of a symphony orchestra, because the Americans knew him only as an opera conductor. This ambition was perfectly linked to the will of the sponsors to bring him back to the United States.

The orchestra was formed between August and September 1920: it consisted of about a hundred musicians who had never played together. The idea of the tour was very ambitious, because an orchestra normally needs a long period of adjustment and, possibly with the same conductor, in order to achieve important results.

Negotiations were finalized with the American sponsors and it was decided that the tour in the United States would begin in December 1920 and would be preceded by two recording sessions at Victor in Camden, near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Toscanini had always refused to make records, because he knew that he could never reach the quality he wanted. In this case, however, the recordings would have brought a substantial contribution in dollars for the tour and therefore Toscanini, albeit reluctantly, accepted.

Of course, since the orchestra had just been formed, after a month of rehearsals, Toscanini wanted to test it with a certain number of concerts, so the trip to the United States was preceded by a first phase around Italy. It began on October 23 at the Milan Conservatory, where all the rehearsals of the pieces that would then be performed took place, and this first part of the tour ended in Naples after 31 concerts. Soon after, the orchestra embarked for the United States and landed in New York in mid-December. The first two weeks in America were occupied with recordings in Camden. For Toscanini it was a real pain: the recording techniques were still very primitive. He confessed that he would gladly have run away, complaining that he could not create the sound he had in mind, but in the end he had to adapt because, as I said, those recordings were also used to finance the tour.

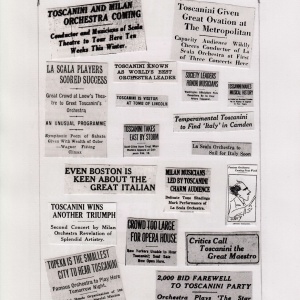

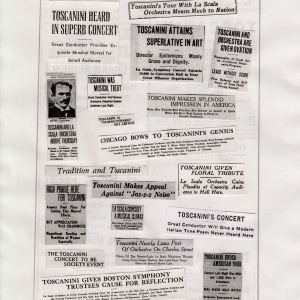

On December 28, 1920 the first concert was held at the Metropolitan in New York, in front of a cheering audience. The American tour was supposed to end in February, but the success was such that it was extended until the end of March. The orchestra also arrived in Canada and the last performance was held in Montreal. In New York, at the beginning, three concerts were planned at the Metropolitan, but the success achieved by Toscanini and his orchestra, thanks also to the very strong participation of Italians in America, forced the organization to program four more concerts in that city, two of which at the Hippodrome. Today it is no longer there, but it was an immense structure, capable of holding six to seven thousand spectators, absolutely unsuitable for a symphonic concert: it usually hosted circus shows, and the animals were housed on the lower floor. A musician later said that, during the performance, an unpleasant odor arrived on the stage…

With the addition of the new concerts, the orchestra was able to embark for Italy only in early April, greeted at the Brooklyn pier by an incredible crowd, mostly made up of our compatriots. The third phase of the tour would then begin in Italy, with another 35 concerts, from April 20 to June 16. In the United States and Canada, there were 59 concerts in 41 cities in 87 days: from December 28, 1920 to March 24, 1921. The total number, which includes the first part in Italy, the second in North America and the third again in Italy, is incredible: because the total of 125 concerts in 237 days gives us an average of one concert every 1.9 days. The distance covered for the various transfers is also incredible. Without considering the two ocean crossings by ship, about 24,000 kilometers were traveled by the orchestra on special trains. These are crazy and unprecedented numbers, which give an idea of the grandeur of this project, which also allowed strengthening the bonds and relations between Italy and the United States, already allied in the First World War.

What music was played during the tour?

Toscanini wanted to present the new orchestra with a complete repertoire, so he proposed cornerstones such as symphonies by Brahms, Beethoven, Mozart and Schubert, and then pieces by great operatic authors such as Wagner, Verdi and Rossini. But above all he wanted to make known, especially in the United States, young contemporary Italian musicians such as Pizzetti, Respighi, De Sabata, Sinigaglia, Pick-Mangiagalli and even Martucci, who had died in 1909. In just over a month of rehearsals, Toscanini managed to give the orchestra an important and extremely varied repertoire, with music by twenty-six different composers, including 18th century authors such as Manfredini and Vivaldi.

The concerts lasted from two to three hours. In his programming, Toscanini was very attentive to the audience he was addressing. In the great American cities on the east coast, he knew he met better-prepared listeners, accustomed to the great symphony orchestras of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, as well as Chicago. As he moved towards the center of the United States, performing in cities that did not have this tradition, Toscanini chose more popular programs, more suited to an audience of non-experts.

In fact, in the United States the orchestra played in big cities but also in lesser-known places...

In America he performed in forty-one cities. Obviously there were the metropolises. Seven concerts were held in New York, then four in Boston, three in Washington and Philadelphia, two in Chicago and Cleveland. But perhaps the most interesting part is that of discovering cities where great music was new and where Toscanini performed in huge areas, certainly not designed for symphonic concerts, such as military arsenals. He didn't care so much about the acoustics, but about finding spaces that could accommodate the largest number of spectators. In Kansas City, for example, where the concert was organized by an important and powerful Masonic Lodge, the orchestra performed in a huge arena that held 10,000 spectators. The tour was heavily advertised in American newspapers, and also touched northern states such as Michigan, Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Nebraska, and further south, Kansas, Oklahoma and the Kentucky: The southernmost city was Tulsa, Oklahoma, and the westernmost city was Wichita, Kansas. The arrival of Toscanini and his orchestra was celebrated and experienced as a great celebration, always with the decisive contribution of the Italian Americans.

In your book you also talk about the discovery by the orchestra and Toscanini himself of jazz, which they hear for the first time during the tour...

It happened in Camden, which is on the other side of the Delaware River from Philadelphia, location of the headquarters of the Victor, which had invented the technology of recording. In the local newspapers the arrival of Toscanini and the recordings of the La Scala orchestra were celebrated as a moment of great progress for all humanity: thanks to the records, wrote the city newspaper, the notes performed in Camden would be heard throughout the world. In the hotel that hosted Toscanini and the orchestra, a jazz trio performed in the evening. In Italy no one had ever heard this type of music, in 1920 it was a discovery for everyone. Among the Italian musicians, many were conservatory professors, therefore educated in classical music. They were intrigued by this new music, and it seems that Toscanini was too: a testimony tells that he enjoyed seeing the drummer throw his sticks in the air and then catch them on the fly.

In reality there is an interview from the first days of January 1921, in a Baltimore newspaper, in which Toscanini gives a very harsh judgment on jazz and defines it as wild music. These are unusual tones for him. I believe that this is due to the fact that Toscanini feared that the explosion of jazz, which in those years had a huge diffusion in the United States, would damage cultured music, risking making Americans forget the importance of symphonic and operatic music. A few years later, in 1928, in an interview with the New York Times Magazine, Toscanini corrected a bit the tone on jazz.

It should be added that in the meantime the Maestro had returned to America as conductor of the New York Philharmonic. In 1928, therefore, he will say that in this musical genre there are many things that can be criticized, but he will also recognize that there are artists of value, even admitting to owning some records. So it can be concluded that there was a sort of rethinking about jazz, at least partial.

The orchestra traveled by train and by ship, and it was a very difficult journey. I was particularly struck by the method suggested by Toscanini to combat seasickness during ocean crossings between Naples and New York...

Toscanini was lucky enough not to suffer from seasickness, indeed when there was a storm he loved to go to the deck to enjoy the show. To help those who were not feeling well during the crossing, he suggested a unique medicine: wine. And so, during the trip, the orchestra consumed the reserve of vin santo that had been offered by Gabriele D'Annunzio. This gesture by D'Annunzio must be explained. With an explicitly political act wanted by Toscanini, in the first part of the Italian tour the orchestra had performed in Fiume, which at that time was occupied by D’Annunzio and his legionaries. Very upset that, after the war, Fiume had not been allocated to Italy, Toscanini had agreed with the occupation of the city and had brought the orchestra to the theater in Fiume where, before and after the concert, D'Annunzio had delivered solemn speeches in honor of the maestro. Toscanini's wife had collected aid and food for the legionaries in Milan as a sign of solidarity and participation. D'Annunzio returned it by donating a gold medal to each of the musicians, who blatantly exhibited it throughout the tour in America because President Wilson had been against, in the peace treaties, ensuring that Fiume would be returned to Italy. As for the vin santo donated by the poet, during the crossing it was appreciated by all the musicians to combat seasickness and beyond.

How was the response of the Italian Americans to the stops of the tour in America? Is it correct to say that for the Italian Americans this tour with its excellence and success was a moment of redemption against the heavy discrimination to which they were subjected?

It is correct, even if the discrimination continued and even affected Toscanini. The Maestro was hugely popular in America, not just for his years at the Metropolitan. During the First World War he had directed a military band at the front, and for this he was awarded a silver medal for valor. In the American newspapers the news of this medal had been a great sensation, many newspapers had even published it prominently on the front page and Toscanini had been defined as a war hero.

But when the orchestra performed in cities where there were other large symphonic ensembles, some American critics pointed out the shortcomings of the Italian musicians, claiming the superiority of the American ones. Especially at the beginning of the tour, the expressions of enthusiasm of our compatriots were underlined with malice and irony. The Italians were described as a people who only knew opera and were unable to judge the value of a symphony orchestra. It should be remembered that the American symphonic tradition was born from the German school, because all the great American orchestras had been formed with musicians of the German school, and even the critics were influenced by it. This explains why Toscanini's interpretations of the great German classics such as Beethoven and Brahms were initially not understood. Some newspapers wrote that Toscanini had conducted Beethoven very well "but as an Italian", and that it was impossible for an Italian to understand Beethoven ... Having said this, in the end even the most snobbish critics changed their minds and the tour ended in an incredible triumph for Toscanini and also for his orchestra.

The success was a source of great pride for the Italian Americans, and this in turn made Toscanini very happy. He was moved by the patriotism and love of the Italians of America, which overwhelmed his usual reserve. Perhaps not everyone knows that Toscanini was a shy man who did not like exaggerated displays of enthusiasm and in particular hated floral tributes, because he said that flowers are offered only to women and the dead. During the tour, in almost all the concerts, the Italian American associations, which obviously ignored this aversion of his, sent little boys dressed in traditional Italian costumes to the stage to offer large bouquets of flowers to the Maestro, as a sign of gratitude. He was always very kind, thanked and accepted the bouquets of flowers and the many gifts that were addressed to him. He even agreed that some mayors would give speeches in his honor before the concerts began. He would never have treated these compatriots, who saw him and the orchestra as messengers from the distant homeland, with rudeness. At the end of the tour it was necessary to build a special wooden box to carry on the ship all the gifts, trophies and various objects, which the numerous associations of compatriots, in the cities touched by the orchestra, had offered to Toscanini.

It should also be remembered that we are talking about a particular historical period: the First World War with which Italy had reacquired Trento and Trieste had just ended, and this helped to transform the concerts into a great patriotic party for all Italian Americans. Toscanini did not like interviews, but after returning from America, also to celebrate the success of this long journey, he granted two, one to Corriere della Sera and one to Il Messaggero. In both he was keen to highlight and magnify the encounter with fellow compatriots in America, the emotion and sentiment felt by him and by his musicians. It is a very nice aspect of this tour.

In 2021 the Teatro alla Scala as we know it today turns 100, with its autonomy and the orchestra founded by Toscanini. Can we say that the beginning of 1921 also derived from the wonderful tour that is the subject of your book and from the great success of the orchestra in America?

In 2021, December 26th marks the 100th anniversary of the refoundation of the Teatro alla Scala, even if the theater has undergone new interventions: in 1946 the reconstruction of the hall after the damage caused by the bombings and then again, at the end of the last century, the restructuring by the architect Botta. Above all, it is 100 years since the birth of the autonomous body and the permanent orchestra, and it is a very important date for La Scala.

A strange thing: when the orchestra was formed, the new Teatro alla Scala had not yet been legally established and the new autonomous entity was not yet there, so that a company was created for the musicians' contracts called Società Italiana Concerti Toscanini. In Italy, both in the first and in the third phase of the tour, it was announced in the posters as Orchestra Toscanini. In the United States, however, the La Scala brand was important and probably the bureaucratic and legal aspects were not so fundamental, so the orchestra was always called the Milan Scala Orchestra. With some bizarre variations: I also found an advertisement where a concert with the Orchestra della Scala of Naples was presented…

Is there a star dedicated to Toscanini on the Hollywood Walk of Fame?

Yes, it was laid on August 2, 1960 and is located at 6725 Hollywood Boulevard.

Is it planned that your book will also be published for the American market?

At the moment the book is out in Italy, but I think this story is also very interesting for American fans and readers, not just those of Italian origin. My publisher, the Italian Music Library, is working to find who might be interested in translating it and distributing it in the United States as well.

You may be interested

-

'Phantom Limb': A Conversation With Dennis...

Dennis Palumbo is a thriller writer and psychotherapist in private practice. He's the auth...

-

“The Hill” St. Louis’ Little Italy

When the fire hydrants begin to look like Italian flags with green, red and white stripes,...

-

30th Annual Art Holiday Walk, Winter Winter...

Holiday walk hours Friday, 12/5 noon-9pm, Saturday ,12/6 noon-9pm Sunday, 12/7 noon-6pm. S...

-

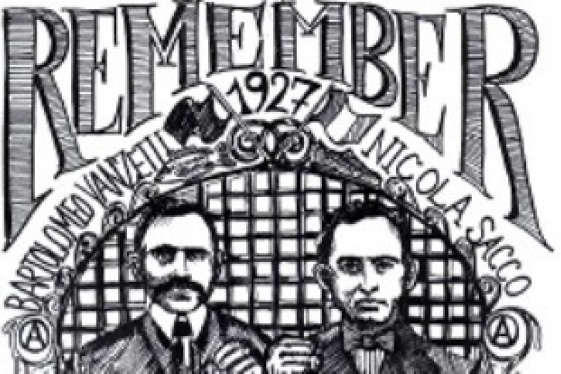

9th Annual Sacco and Vanzetti March/Rally

Saturday, August 23rd, in Boston, the 87th anniversary of the execution of Nicola Sacco an...

-

A Week in Emilia Romagna: An Italian Atmosp...

The Wine Consortium of Romagna, together with Consulate General of Italy in Boston, the Ho...

-

An Unlikely Union: The love-hate story of Ne...

Award-winning author and Brooklynite Paul Moses is back with a historic yet dazzling sto...

-

Bocce with the Brothers

Annual Bocce with the Brothers fundraiser for Capuchin Ministries will be held from 6 to 1...

-

Cathedral of St. John the Divine, Oratorio S...

For the first time ever, The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, in collaboration with the O...