April 17, 2024, marks the 500th anniversary of the first entry of someone from the Old World into New York Bay. It was, of course, an explorer from the lands now called Italy: Giovanni da Verrazzano. We the Italians could not miss this very important date with history.

We talk about it with admiration, pride and gratitude, hosting a great researcher, an enormously successful historian, who discovered incredible things, collected in a newly published book, "Leonardo da Vinci and Verrazzano's Royal Discovery of New York." We welcome Prof. Stefaan Missinne, thanking him very much indeed for his kind helpfulness.

Professor, the first question is about the hero of the year, Giovanni da Verrazzano. Can you briefly tell us who he was?

I thank you for this interview.

Giovanni da Verrazzano (c. 1485-1528) describes himself in an elegant style to the Christian King Francis I of France. He writes he is the King´s humble servant as well as an inventor, thereby meaning discoverer. This is rather surprising.

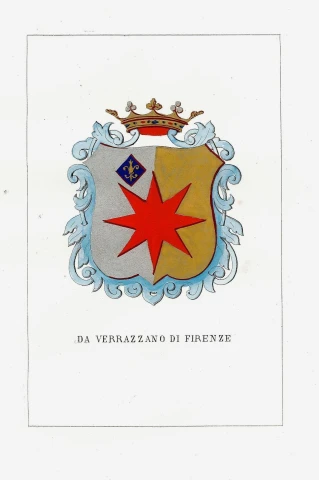

Verrazzano is indeed a very important Italian navigator. During his epic journey 500 years ago, he mistook the inland waters of Pamlico Sound for an open strait leading to the Far East, but that does not diminish his importance in the history of discoveries. Interestingly, apparently no one has noticed that this Tuscan's family crest is the Marian eight-pointed star. I noticed it during a visit in the castle of Verrazzano because it hangs there on the exterior wall. On a modern version it is combined with the French lily because he was in the royal service of the King of France.

It is this Italian explorer who is commemorated this year for being the first in Early Modern history to discover life in the New World on the American east coast.

He came from a village in the Chianti wine region in Tuscany known as Greve in Chianti. It has apparently been forgotten that he was the first to describe the coastal areas of the North American East Coast, including New York.

His original travelogue that has survived uniquely illustrates the earliest detailed contact with native North Americans during his more than ten landings on the American east coast. The natives Verrazzano appears to have encountered from south to north included the Waccamaw and Pee Dee, the Cape Fear, Algonquians, Lenni Lenape and the Narrangansett. This short list is indicative only.

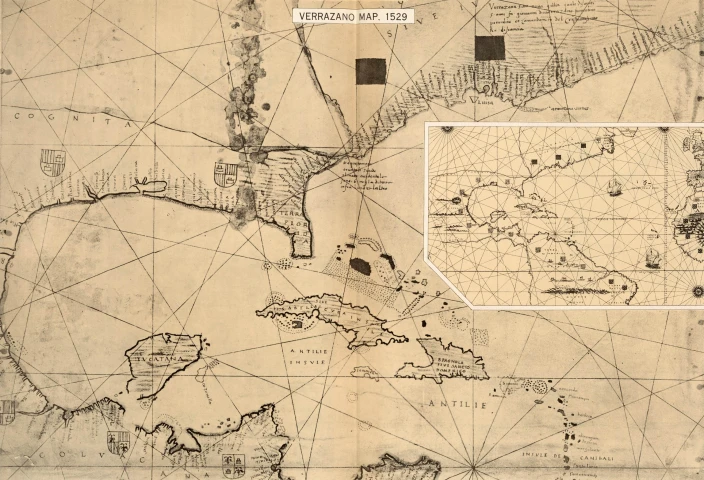

Verrazzano's voyage of 1524 made first-time history that there was a connection between the English and Portuguese discoveries in the north (Newfoundland) and those of the Spanish in the Caribbean.

Some additional character traits of Verrazzano were that he was an open-minded humanist. Giovanni da Verrazzano can certainly be seen in the same ranks as other Italian compatriots known as explorers such as Columbus, Vespucci and Caboto.

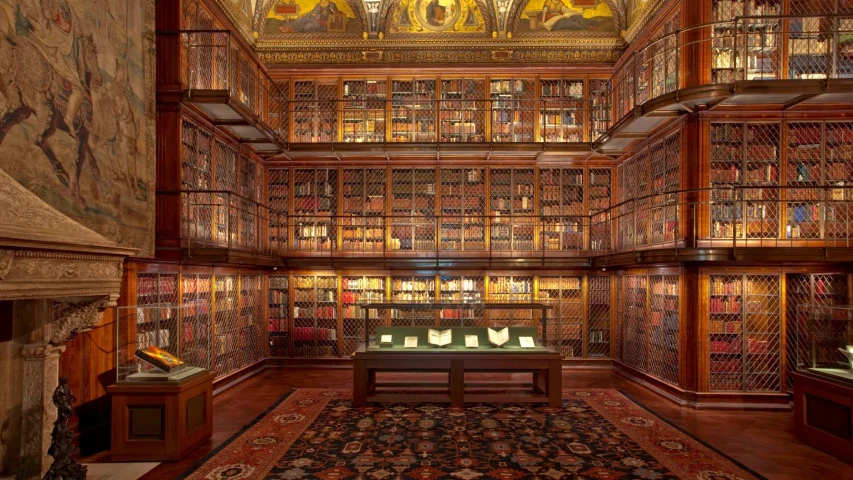

A great advantage for my research was that the Pierpont Morgan Library preserved Verrazzano's historical literary birth certificate of New York. This historical document is now five hundred years old, as it is dated 1524.

The five hundredth anniversary of the discovery of the American East Coast is an opportunity to give this famous Italian the historical attention he deserves.

The naming of the suspension bridge over the Narrows in New York after Verrazzano, which opened in January 1964, has made the Verrazzano name known to a wider American and international audience.

Five hundred years ago Verrazzano was the first European to enter New York Bay. But his journey and his enterprise was much more than that. I was struck by the huge number of references you discovered in different places on the east coast of the United States. Your book contains them all, but I ask you to give some previews to our readers.

I appreciate you were struck by the numerous new references and findings that I discovered in the travel report of Verrazzano. To better understand, it is important to know that because of the late discovery of the Cèllere Codex, Verrazzano´s travel report has been misinterpreted historically and in the history of cartography specifically.

In the 19th century, Verrazzano was believed to be the result of a fictitious fabrication and a mistaken identity. Therefore, his chronicled report, his exploration, and discovery of unknown lands on the US East Coast has been forgotten in history for many years.

My new book published by Cambridge Scholars Publishing on March 14th 2024 is based on a laborious revision of data and a meticulous research. Initially I only wanted to write an article. But the more I read about Verrazzano, the more I noticed that most authors used existing sources from others without really generating new findings. And having written about Leonardo, I wondered if these two extraordinary Tuscans living in exile in France had known each another.

I was astonished to discover so many new underlying aspects in his travel report. This new volume with many pictures is expected redraw some of the contours of Renaissance scholarship regarding this valuable Italian humanistic explorer and his environment. He sailed along the coastline of the following US States: South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Maine. He passed by Nova Scotia and Newfoundland in Canada before returning to France.

For the naming of different geographical areas (cape, island, land, port, shoals), Verrazzano uses the family names of political heavyweights of several of the different French noble houses including the Valois, Orléans, Bourbon, Savoy, and Lorraine, among others. Just to give a few examples of the who is who of the French nobility in the place names by Verrazzano: The Valois-Angoulême (Santa Margarita for the Bay of New York), the Valois-Alençon (Cape Lanzone for Cape May in New Jersey, on the Isthmus of Delaware Bay), the Lorraine (Coast of Lorrenna for the cardinal, son of René II, Duke of Lorraine, for the Delaware coastline), the Gouffier (Cape Bonivetto, for the area around Atlantic City in New Jersey), the Bourbon-Vendôme (Vandoma River, for the Delaware River), the Bourbon-Condé (Little St. Pol Mountain, for the Atlantic Highlands), the Valois-Angoulême (Angoulême – for New York), the Savoy (Island of Louise, for Martha´s Vineyard in Massachusetts) and the d’Albret (Three Daughters of Navarra living at the French court in exile, for Deer Island, Vinal Haven and Island Au Haut on the Coast of Maine).

This is a first in American history and a tentative filling of a gap in the American-French-Italian scholarship. It is not known that any other discoverer was so “classical”, yet even political. Verrazzano gave balanced attention to members and even fractions of a royal court, in this case the French royal court.

In addition, some of his so-called ethnological placenames are puns with a pictorial content chosen by Verrazzano to define a specific person.

The Tuscan sailor linked the plight of exiles to islands, which have an ambivalent character as a place of solitude and isolation, but also of safety and refuge. These puns are a first in the literature on Giovanni da Verrazzano. Scholars in the history of American cartography may recall René II, Duke of Lorraine who sponsored the humanist circle in St. Dié and who played a key role to create the 1507/1515 large world map of Martin Waldseemüller now at the Library of Congress.

A new finding is the iconographic meaning of the toponym Armelline sandbank. It refers to the whiteness of the sea foam around it. Verrazzano chooses the word of a well-known animal, namely the ermine, thus connecting the whitecaps of the surface of the sea to the unmistakable coat of arms of Queen Claude of France. She is the reigning Duchess of Brittany from the powerful House of Valois-Orléans.

Verrazzano finds captivating suitable ways to include the surnames of his sponsors, like Gondi, in his toponyms without offending his royal patron. Moreover, the longer he sailed onward north along the US East Coast, the more the “Italian influence” of his homeland and the neighboring Mediterranean (Rhodes, Sicily, Dalmatia, Illyria, etc.) became a suitable part of the comparative and vivid description of the new places he finds and names.

Your book is called "Leonardo da Vinci and Verrazzano's Royal Discovery of New York." What relationship linked these two Tuscan greats?

In my research I found that Leonardo and Verrazzano were acquainted with the same members of very powerful French families. They both worked for the same royal patron, King Francis I of France, and both had contacts with other members of the royal family, including the king’s very dominant mother, Louise of Savoy.

In addition, Leonardo and Verrazzano were part of a big network and they even shared the very same Italian acquaintances, including many Tuscans and other Italians living in exile in France. These included members of the Medici, Gondi, Ridolfi, Rucellai, Rustici, Pallavicino, Benci and Giovio families.

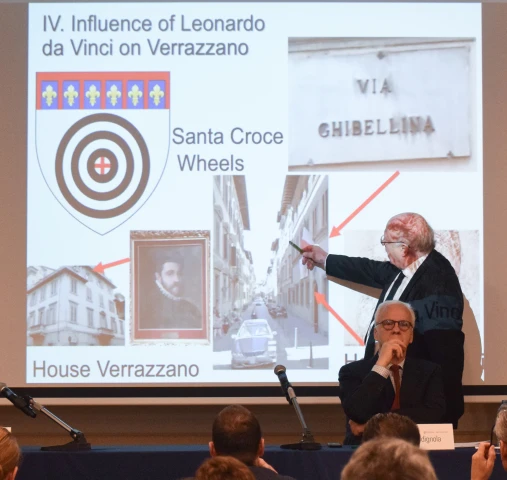

A big surprise was that I found, with the help of Prof. Laura Cassi from Florence that the Vinci and Verrazzano families were neighbors who lived on busy Via Ghibellina Street in Florence. They shared the Florentine banner of the Santa Croce and even the banner of the subdivision of their locality, the one of the quarter wheel. This heraldic banner represented their immediate Florentine neighborhood.

What relationship further linked these two Tuscan luminaries?

As the research progressed, I came across more and more connections between the two. To name just a few: Verrazzano mentions the name of the French ambassador who accompanied Leonardo to France for Race Point in Massachusetts. Moreover, Verrazzano chooses the name of the wife of the cousin, Leonardo’s father´s banker (A. Gondi), for a strategically important island rock, now known as Rose Island, at the entry in Newport Harbor.

In any case, it is an impressive fact that the leading financial world capital of the world, New York was discovered by means of the key crowd financing provided by the nephew of Leonardo da Vinci´s father´s banker. Verrazzano chooses the name of the cartographer Paolo Giovio, who will later become Leonardo's first biographer and even his own, for Point Judith in the US State of Rhode Island. Verrazzano's travelogue even ends up in the library of the aforementioned Paolo Giovio.

The name of a cape near Atlantic City in New Jersey Verrazzano reserves for Leonardo's friend, the French admiral Bonnivet.

On top of that, Verrazzano names the New York marina after Margarita, the king's sister who was patron of Leonardo's works. It would, of course, have been even more obvious if Verrazzano would have named a rock or inlet on the US East Coast after Leonardo.

Nevertheless, there are numerous so-called pieces of circumstantial evidence, but one of course asks if these can be seen as an irrefutable proof that Leonardo influenced his younger compatriot?

The answer is yes. This evidence lies in the extremely small deviation of only 0.4% between the one-time value of the size of the world written down by Verrazzano in his travelogue and the unpublished value given by Leonardo 20 years before. This is irrefutable mathematical evidence that Giovanni da Verrazzano was influenced prior to his departure by his famous Tuscan fellow companion Leonardo da Vinci. Most likely, this happened via the close family ties between the Benci and the Gondi families.

Italian family ties and international networks in Renaissance have been known to be very important. I discovered at the end of writing this book that a certain Costanza Benci married Bernardo Gondi in Florence in June of 1517.

Originally, in the 14th century, the Benci/Benchi were called Usacchi (or Isacchi) and were possibly of Jewish origin. Later, the Usacchi family changed its surname to that of de' Benci. The origin of the word bank stems from the Italian word “banco” which means bench. The cultured Benci family was a Florentine patron of Leonardo da Vinci and an important banking family.

But could this Costanza Benci be related to Giovanni Benci and her even more famous sister Ginevra Benci? Initially this trace had a dead end. But I found that Costanza Benci had several children. Two of Costanza´s children were baptized in the name of Amerigo Gondi, born in 1530 and Ginevra Gondi born in 1531.

But was this a possible sign Costanza Benci of a relationship related to the famous Ginevra Benci painted by Leonardo da Vinci? In Italy, and in many other places of the world, is not uncommon for children to be named after their ancestors. With the personal help of the Marchioness of the famous Gondi family in Florence, it was possible to clear up this mystery.

The surprising answer was that Costanza Benci was the daughter of Bartolomeo Benci, who in turn was the brother of Amerigo Benci. And Amerigo Benci was the father of Ginevra Benci whose portrait was painted by Leonardo da Vinci. Costanza and Ginevra and her brother Giovanni were thus full cousins. In other words, a direct family relationship existed between the banker Amerigo Benci, his children including Giovanni Benci (and his famous portrayed sister Ginevra) and the children of Bartolomeo Benci and his daughter Costanza who married Bernardo Gondi in 1517. The above family connection takes on a special hue as Leonardo da Vinci deposited his world globe depicting an open sea route to China, chosen by Verrazzano, with his friend Giovanni Benci in Florence. This is a new fragment in an incredible historical setting, and it provides the scientific basis for a credible conjunction.

In 2012 you discovered the Da Vinci Globe, and this has a fundamental importance for the topic of your book and of this interview. Please tell us more, I personally find your discovery exciting!

The discovery of da Vinci's iconic 1504 globe in London during the Royal Geographical Society's in London in 2012 was indeed a serendipity.

The scientific research that provided irrefutable evidence of Leonardo´s authorship took six years. It showed that Leonardo not only knew that the new world had been discovered. He was even the first to make a globe of it. To do so, this genius Italian Renaissance artist used two lower shells from two ostrich eggs.

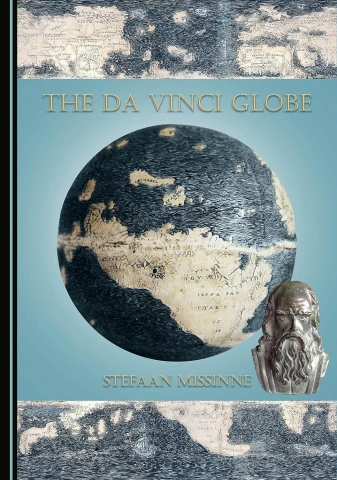

These eggs originated from ostriches from the garden of Pavia castle. His globe is the oldest globe in history on which the names of many countries, including Brazil, Judea, China, Germany, etc. are engraved. This story was published in 2018 in my book “The da Vinci Globe”, by Cambridge Scholars Publishing, highly recommended for any reader who wants to follow an exciting investigation.

In 2018, not yet planning to write about the quincentennial of Verrazzano, I wrote about the brother of Verrazzano whose map is kept at the Vatican Museum. I had inspected this map. I had noticed its erroneous and mythical Verrazzanian Sea, linking a narrow isthmus on the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific. On the da Vinci Globe an open sea passage to the eastern coast of Asia is portrayed.

In the Codex Atlanticus, page 331 recto, dating from 1504, Leonardo writes “El mio mappamondo che ha Giovanni Benci” which in English means: My world globe that has Giovanni Benci. Leonardo's earth diameter of 7.000 miles is reflected in the scale of the da Vinci Globe at 1/80.000.000. The Italian nautical mile he uses is 1.280 meter per mile. Leonardo´s definition allows to compare with what Verrazzano wrote down in miles with regarding to the circumference of the world on the 34th parallel north.

As luck would have it, there is a physical and historical connection between the place of storage where the 1524 document with the literary discovery of New York, the earliest cartographic birth certificate with the first-ever naming of America dating from c. 1507 and with the twin of the da Vinci Globe dating from 1504.

What is rather unique in the world is that the New York Public Library's Rare Book Department, which houses the Lenox Globe dating from 1504, a copper cast globe, without any green or black patina, replica of the da Vinci Globe, also has the epic cartographic birth certificate of the USA dating from c. 1507.

In contrast, the Pierpont Morgan Library houses Verrazzano's historic literary birth certificate of New York dating from 1524 with information on the size of the world based on the da Vinci Globe.

Both libraries are in Manhattan. They are located only five blocks and a street corner away from each other, namely Madison Avenue/E 41 Street, and nobody seems to have noticed these valuable historic Americana treasures (yet).

Now that your book is published, what are the conclusions you have come to regarding this historic event that saw 500 years ago the lands that would later become Italy and the United States as protagonists?

My new book is available via www.cambridgescholars.com and it unveils for the first time in history the background and deeper meaning of Verrazzano´s choice of placenames. These have in the past have not been correctly understood. His travelogue is much more than report. It is a personal testimony of an Italian that discovered large parts of the coastline of the East of the United States. The names of the geographical locations, as given by Verrazzano, can be linked to his experience as a navigator, his social context and setting in life.

It was believed that Verrazzano, a pioneer of globalization, named locations after trees and plants, imprecisely identified as due to a botanical interest. However, I offer the evidence that their symbolic meaning including the religious connotation, which fits within the Renaissance iconography, ought to have been considered. It may be assumed that Verrazzano was in France several years prior to 1521. Most likely Verrazzano looked for a new employer in France in 1518 with the updated cartographic knowledge he had gathered in Lisbon and Seville.

What gives an idea of the cartographic information that Verrazzano might have learned during his sojourn in Lisbon and Seville in 1517 can be seen on a small world map based on a design by Leonardo da Vinci. It is noteworthy to mention an inconspicuous sheet of globe gores found among the papers in the handwriting of Leonardo.

The reason why these, dating from c. 1515, are relevant is that they are the only contemporary ones to depict Florida as an island, which was discovered in 1513, and the open western seaway on the 34th parallel north between Florida and Bacalar (Newfoundland). Verrazzano selected this supposed open sea route for his daring enterprise in 1524, trying to reach Cathay (China).

To his royal employer, Verrazzano appeared to be a diplomatic, courteous, and erudite humanist. He knowledge of the Holy Scripture is remarkable. This Tuscan “astronaut” of the early sixteenth century recalls personalities like Pierrevive and Giovio, not because of their religious or military importance but because of their intellect and cultural influence in society.

The ancients play a role in Verrazzano’s discourse. Although Verrazzano corrects Aristotle and Ptolemy and refers to other ancients including Virgil’s Archadia, the calculation of the Italian of the world’s dimension is typical for the Renaissance.

With this study, Verrazzano can now, among many things, be remembered as the discoverer of New York. His was the first Early Modern exploration of the US East Coast. Verrazzano is an inspiration for many Italians in the New World up to this day. A sign that Verrazzano is treasured in the USA is that everyone knows the large bridge in New York that carries his name.

You are a collector of old maps and globes; and a member of several world recognized Institutions, among which the Washington Map Society, the Leonardo da Vinci Society, the International Society for the History of the Map. No one among the people I know has more knowledge to answer this last question, which applies to any event that happened or person who lived 500 years ago (any reference to Christopher Columbus is by no means coincidental). Does it make any sense, is it correct, is it honest, to claim and compel others to judge the world of five centuries ago with the mindset, principles, and attitudes of today?

I thank you for your kind compliment. I think it is a natural development, largely influenced by the media. People interpret history through the glasses they use to watch TV and films every day, and maybe even when reading newspapers. It is important to learn history to know the future. I think there is a saying that history repeats itself. There is a lot of important geographical knowledge in old maps and globes. These reflect the historical interpretation of the time of and before the making of these maps. Not all of them are always very up to date, but they do provide a picture of national influences and historical borders. It helps to better understand the contemporary situation in many countries of the world. How history and its education are handled in the community is an indicator of how history is valued. It makes no sense to try to reinterpret history with today's values. This tentative reinterpretation may foreshadow how society will evolve.

In Verrazzano´s Italian travelogue, Codex Cèllere, a key document in the history of America, Verrazzano describes what the King of France asked him to do: To find the seaway to China. The Tuscan’s achievement was—as a victorious navigator who graciously made it with his crew and crossed the unknown oceanic waters in a single ship—a first in history.

Less than a century later, in 1607, Chesapeake Bay would be the point of entry for the English immigrants and their successful settlements on the borders of the James River at Jamestown, Virginia. I suspect many people have never heard of Verrazzano nor of his travelogue and its vivid descriptions. The book I wrote serves to make his American history and him better known. It is more than just a repetition of the descriptions. It offers a unique perspective for the reader to better understand Verrazzano´s historical setting and his background. Therefore, it makes more sense to learn to historically assess the world of five centuries ago and, as a result, to understand the thinking, the principles, and the attitudes of the time past to better comprehend the present.

Coincidentally, Ettore Ximenes' (1855-1926) magisterial 1909 bronze monument of Giovanni da Verrazzano in Battery Park in New York stands on a 1952 pedestal. It is made of granite taken from Deer Island, one of the three islands named after the Navarrese princesses to which the Tuscan referred in his travelogue.

In other words, the Italian explorer is now standing on a stone related to the three islands of princesses of Navarra named by Giovanni da Verrazzano. One of these islands is now called Deer Island on the coast of Maine. I think this happened rather by accident. Whether this is important one might ask. I would say no. But perhaps the American schoolchildren who later visit Battery Park in New York will learn that Verrazzano's 500-year-old history is intimately connected to that of America's present without unnecessarily being reinterpreted with 21st century values. The century-old stone from Deer Island is proof of it.

Making an exception, I end this interview with a personal remark attributable only to me, Umberto Mucci, and not to Professor Missinne. In 1528, during his third expedition, Verrazzano was captured and devoured (yes, devoured) by a tribe of cannibals. With the utmost respect and total sympathy to Native Americans for all the harm that has been done to them (not by Columbus), the next time you hear someone describe Christopher Columbus as the villain of the story who arrives in a supposedly peaceful and wonderful earthly paradise, and brings evil among natives who are thoughtful, happy and kind to one another, remind them of the end that befell this other outstanding explorer, in what was anything but an earthly paradise of peace and prosperity.

Il 17 aprile 2024 ricorre il cinquecentesimo anniversario della prima entrata di qualcuno proveniente dal vecchio mondo nella baia di New York. Era, ovviamente, un esploratore proveniente dalle terre che oggi si chiamano Italia: Giovanni da Verrazzano. We the Italians non poteva mancare questo importantissimo appuntamento con la storia.

Ne parliamo con ammirazione, orgoglio e gratitudine, ospitando un grande ricercatore, uno storico di enorme successo, che ha scoperto cose incredibili, raccolte in un libro appena pubblicato: "Leonardo da Vinci and Verrazzano's Royal Discovery of New York". Diamo il benvenuto al Prof. Stefaan Missinne, ringraziandolo davvero moltissimo per la sua disponibilità.

Professore, la prima domanda riguarda l'eroe dell'anno, Giovanni da Verrazzano. Può dirci brevemente chi era?

La ringrazio per questa intervista.

Giovanni da Verrazzano (1485 ca. - 1528) si descrive in uno stile elegante al re cristiano Francesco I di Francia. Scrive di essere un umile servitore del re e un inventore, cioè uno scopritore. Questo è piuttosto sorprendente.

Verrazzano è infatti un navigatore italiano molto importante. Durante il suo epico viaggio di 500 anni fa, scambiò le acque interne del Pamlico Sound per uno stretto aperto che portava in Estremo Oriente, ma questo non sminuisce la sua importanza nella storia delle scoperte. È interessante notare che nessuno ha notato che lo stemma della famiglia di questo toscano è la stella mariana a otto punte. L'ho notato durante una visita al castello di Verrazzano perché è appeso alla parete esterna. In una versione moderna è abbinata al giglio francese perché era al servizio reale del re di Francia.

È questo esploratore italiano che viene commemorato quest'anno per essere stato il primo nella storia della prima età moderna a scoprire la vita nel Nuovo Mondo, sulla costa orientale americana.

Egli proveniva da un villaggio della regione vinicola del Chianti, in Toscana, noto come Greve in Chianti. Sembra che il mondo abbia dimenticato che fu il primo a descrivere le aree costiere della costa orientale del Nord America, compresa New York.

Il suo diario di viaggio originale, che si è conservato, illustra in modo unico il primo contatto dettagliato con i nativi nordamericani durante i suoi oltre dieci sbarchi sulla costa orientale americana. Tra i nativi che Verrazzano sembra aver incontrato da sud a nord ci sono i Waccamaw e i Pee Dee, i Cape Fear, gli Algonqui, i Lenni Lenape e i Narrangansett. Questo breve elenco è puramente indicativo.

Il viaggio di Verrazzano del 1524 fece passare per la prima volta alla storia l'esistenza di un collegamento tra le scoperte inglesi e portoghesi nel nord (Terranova) e quelle spagnole nei Caraibi.

Alcuni ulteriori tratti caratteriali di Verrazzano erano che era un umanista aperto e di larghe vedute. Giovanni da Verrazzano può certamente essere considerato alla stregua di altri compatrioti italiani noti come esploratori come Colombo, Vespucci e Caboto.

Un grande vantaggio per la mia ricerca è stato che nella Pierpont Morgan Library è conservato lo storico atto di nascita letterario di Verrazzano a New York. Questo documento storico ha ormai cinquecento anni, essendo datato 1524.

Il cinquecentesimo anniversario della scoperta della costa orientale americana è un'occasione per dare a questo famoso italiano l'attenzione storica che merita.

L'intitolazione a Verrazzano del ponte sospeso sui Narrows di New York, inaugurato nel gennaio 1964, ha fatto conoscere il nome di Verrazzano a un pubblico americano e internazionale più vasto.

Cinquecento anni fa Verrazzano fu il primo europeo a entrare nella baia di New York. Ma il suo viaggio e la sua impresa furono molto di più. Mi ha colpito l'enorme numero di riferimenti che lei ha scoperto in diversi luoghi della costa orientale degli Stati Uniti. Il suo libro li contiene tutti, ma le chiedo di dare qualche anticipazione ai nostri lettori.

Apprezzo che sia stato colpito dai numerosi nuovi riferimenti e reperti che ho scoperto nel resoconto di viaggio di Verrazzano. Per capire meglio, è importante sapere che, a causa della tardiva scoperta del Codice Cèllere, il resoconto di viaggio di Verrazzano è stato male interpretato dal punto di vista storico e della storia della cartografia in particolare.

Nel XIX secolo si riteneva che Verrazzano fosse il risultato di una montatura fittizia e di un errore di identità. Pertanto, il suo resoconto, la sua esplorazione e la scoperta di terre sconosciute sulla costa orientale degli Stati Uniti sono stati dimenticati dalla storia per molti anni.

Il mio nuovo libro, pubblicato da Cambridge Scholars Publishing il 14 marzo 2024, si basa su una laboriosa revisione dei dati e su una ricerca meticolosa. Inizialmente volevo scrivere solo un articolo. Ma più leggevo su Verrazzano, più notavo che la maggior parte degli autori utilizzava fonti già esistenti di altri, senza generare realmente nuove scoperte. E avendo scritto di Leonardo, mi sono chiesto se questi due straordinari toscani che vivevano in esilio in Francia si fossero conosciuti.

Mi ha stupito scoprire tanti nuovi aspetti di fondo nel suo resoconto di viaggio. Questo nuovo volume, corredato da molte immagini, dovrebbe ridisegnare alcuni dei contorni dell'erudizione rinascimentale su questo prezioso esploratore umanistico italiano e sul suo ambiente. Egli navigò lungo le coste dei seguenti Stati americani: Carolina del Sud, Carolina del Nord, Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New Hampshire e Maine. Passò dalla Nuova Scozia e da Terranova in Canada prima di tornare in Francia.

Per la denominazione delle diverse aree geografiche (promontori, isole, terre, porti, secche), Verrazzano utilizza i nomi delle famiglie di peso politico di diverse case nobiliari francesi, tra cui i Valois, gli Orléans, i Borbone, i Savoia e i Lorena. Solo per fare qualche esempio del who is who della nobiltà francese nei toponimi di Verrazzano: I Valois-Angoulême (Santa Margherita nella baia di New York), i Valois-Alençon (Capo Lanzone a Cape May nel New Jersey, sull'istmo della baia del Delaware), i Lorena (Costa di Lorrenna per il cardinale, figlio di René II, Duca di Lorena, nella costa del Delaware), la Gouffier (Capo Bonivetto, nell'area intorno ad Atlantic City nel New Jersey), la Bourbon-Vendôme (fiume Vandoma, sul fiume Delaware), la Bourbon-Condé (Little St. Pol, nelle Highlands atlantiche), i Valois-Angoulême (Angoulême – a New York), i Savoia (Isola di Louise a per Martha's Vineyard nel Massachusetts) e i d'Albret (Tre figlie di Navarra che vivono alla corte francese in esilio, a Deer Island, Vinal Haven e Island Au Haut sulla costa del Maine).

Si tratta di una novità assoluta nella storia americana e di un tentativo di colmare una lacuna nel mondo del sapere americano-francese-italiano. Non risulta che nessun altro scopritore sia stato così "classico", eppure anche politico. Verrazzano dedicò un'attenzione equilibrata ai membri e persino alle frazioni di una corte reale, in questo caso la corte reale francese.

Inoltre, alcuni dei suoi cosiddetti toponimi etnologici sono giochi di parole con un contenuto pittorico scelto da Verrazzano per definire una persona specifica.

Il marinaio toscano collegava la condizione degli esuli alle isole, che hanno un carattere ambivalente in quanto luogo di solitudine e isolamento, ma anche di sicurezza e rifugio. Questi giochi di parole sono una novità assoluta nella letteratura su Giovanni da Verrazzano. Gli studiosi di storia della cartografia americana ricorderanno René II, duca di Lorena, che sponsorizzò il circolo umanistico di St. Dié e che ebbe un ruolo fondamentale nella creazione del grande mappamondo del 1507/1515 di Martin Waldseemüller, ora alla Biblioteca del Congresso.

Una nuova scoperta è il significato iconografico del toponimo Armelline sandbank. Si riferisce al candore della schiuma del mare che lo circonda. Verrazzano sceglie il termine di un animale ben noto, l'ermellino, collegando così le bianche scogliere della superficie del mare all'inconfondibile stemma della regina Claude di Francia. È la duchessa regnante di Bretagna della potente casata dei Valois-Orléans.

Verrazzano trova modi accattivanti e adatti per includere i cognomi dei suoi sponsor, come Gondi, nei suoi toponimi senza offendere il suo patrono reale. Inoltre, più navigava verso nord lungo la costa orientale degli Stati Uniti, più l'"influenza italiana" della sua patria e del Mediterraneo vicino (Rodi, Sicilia, Dalmazia, Illiria, ecc.) diventava una parte adeguata della descrizione comparativa e vivida dei nuovi luoghi che trovava e nominava.

Il suo libro si intitola "Leonardo da Vinci and Verrazzano's Royal Discovery of New York". Che rapporto c'è tra questi due grandi toscani?

Nelle mie ricerche ho scoperto che Leonardo e Verrazzano conoscevano gli stessi membri di famiglie francesi molto potenti. Entrambi lavoravano per lo stesso mecenate reale, il re Francesco I di Francia, ed entrambi avevano contatti con altri membri della famiglia reale, tra cui la madre molto predominante del re, Luisa di Savoia.

Inoltre, Leonardo e Verrazzano facevano parte di una grande rete e condividevano persino le stesse conoscenze italiane, tra cui molti toscani e altri italiani che vivevano in esilio in Francia. Tra questi vi erano membri delle famiglie Medici, Gondi, Ridolfi, Rucellai, Rustici, Pallavicino, Benci e Giovio.

Una grande sorpresa è stata quella di scoprire, con l'aiuto della professoressa Laura Cassi di Firenze, che le famiglie Vinci e Verrazzano erano vicine di casa e vivevano nella trafficata via Ghibellina a Firenze. Condividevano lo stendardo fiorentino di Santa Croce e anche lo stendardo della suddivisione della loro località, quello del quarto di ruota. Questo stendardo araldico rappresentava il loro immediato quartiere fiorentino.

Quale rapporto legava ulteriormente questi due luminari toscani?

Man mano che la ricerca procedeva, mi sono imbattuto in un numero sempre maggiore di connessioni tra i due. Per citarne solo alcuni: Verrazzano cita il nome dell'ambasciatore francese che accompagnò Leonardo in Francia a Race Point nel Massachusetts. Inoltre, Verrazzano sceglie il nome della moglie del cugino banchiere del padre di Leonardo (A. Gondi) per uno scoglio isolano di importanza strategica, oggi noto come Rose Island, all'ingresso del porto di Newport.

In ogni caso, è un fatto impressionante che la principale capitale finanziaria del mondo, New York, sia stata scoperta grazie al fondamentale finanziamento pubblico fornito dal nipote del banchiere del padre di Leonardo da Vinci. Verrazzano sceglie il nome del cartografo Paolo Giovio, che in seguito diventerà il primo biografo di Leonardo e anche il suo, per dare il nome a Point Judith, nello Stato americano del Rhode Island. Il diario di viaggio di Verrazzano finisce addirittura nella biblioteca del suddetto Paolo Giovio.

Il nome di un promontorio vicino ad Atlantic City, nel New Jersey, Verrazzano lo riserva all'amico di Leonardo, l'ammiraglio francese Bonnivet.

Inoltre, Verrazzano intitola il porto turistico di New York alla sorella del re, Margherita, mecenate delle opere di Leonardo. Naturalmente sarebbe stato ancora più ovvio se Verrazzano avesse dato il nome di Leonardo a uno scoglio o a un'insenatura della costa orientale degli Stati Uniti.

Tuttavia, esistono numerose prove indiziarie, ma ci si chiede se queste possano essere considerate una prova inconfutabile del fatto che Leonardo abbia influenzato il suo compatriota più giovane.

La risposta è sì. Questa prova risiede nello scostamento estremamente ridotto, pari solo allo 0,4%, tra il valore unico delle dimensioni del mondo scritto da Verrazzano nel suo diario di viaggio e il valore inedito fornito da Leonardo 20 anni prima. Si tratta di una prova matematica inconfutabile che Giovanni da Verrazzano è stato influenzato, prima della sua partenza, dal suo famoso conterraneo toscano Leonardo da Vinci. Molto probabilmente ciò avvenne attraverso gli stretti legami familiari tra le famiglie Benci e Gondi.

I legami familiari italiani e le reti internazionali nel Rinascimento sono noti per essere molto importanti. Ho scoperto alla fine della stesura di questo libro che una certa Costanza Benci sposò Bernardo Gondi a Firenze nel giugno del 1517.

Originariamente, nel XIV secolo, i Benci/Benchi si chiamavano Usacchi (o Isacchi) e forse erano di origine ebraica. In seguito, la famiglia Usacchi cambiò il proprio cognome in quello di de' Benci. L'origine della parola banca deriva dall'italiano "banco". La colta famiglia Benci era un'importante famiglia di banchieri mecenati, che finanziò Leonardo da Vinci.

Ma questa Costanza Benci potrebbe essere imparentata con Giovanni Benci e con la sua ancor più famosa sorella Ginevra Benci? Inizialmente questa traccia era un vicolo cieco. Ma ho scoperto che Costanza Benci aveva diversi figli. Due dei figli di Costanza furono battezzati a nome di Amerigo Gondi, nato nel 1530 e Ginevra Gondi nata nel 1531.

Ma era questo un possibile segno che Costanza Benci avesse una relazione con la famosa Ginevra Benci dipinta da Leonardo da Vinci? In Italia, e in molti altri luoghi del mondo, non è raro che i bambini prendano il nome dei loro antenati. Con l'aiuto personale della Marchesa della famosa famiglia Gondi di Firenze, è stato possibile chiarire questo mistero.

La risposta sorprendente è stata che Costanza Benci era figlia di Bartolomeo Benci, che a sua volta era fratello di Amerigo Benci. E Amerigo Benci era il padre di Ginevra Benci, il cui ritratto fu dipinto da Leonardo da Vinci. Costanza, Ginevra e suo fratello Giovanni erano quindi cugini a tutti gli effetti. In altre parole, esisteva una relazione familiare diretta tra il banchiere Amerigo Benci, i suoi figli tra cui Giovanni Benci (e la sua famosa sorella ritratta Ginevra) e i figli di Bartolomeo Benci e di sua figlia Costanza che sposò Bernardo Gondi nel 1517. Il legame familiare di cui sopra assume una sfumatura particolare nel momento in cui Leonardo da Vinci depositò a Firenze, presso l'amico Giovanni Benci, il suo mappamondo raffigurante una rotta marittima aperta verso la Cina, scelta da Verrazzano. Si tratta di un nuovo frammento in un contesto storico incredibile, che fornisce le basi scientifiche per una congiunzione credibile.

Nel 2012 lei ha scoperto il Globo di Da Vinci, e questo ha un'importanza fondamentale per il tema del suo libro e di questa intervista. Ci dica di più, personalmente trovo la sua scoperta emozionante!

La scoperta dell'iconico mappamondo da Vinci del 1504 a Londra durante la Royal Geographical Society nel 2012 è stata davvero una serendipità.

La ricerca scientifica che ha fornito prove inconfutabili della paternità di Leonardo è durata sei anni. Ha dimostrato che Leonardo non solo sapeva che il nuovo mondo era stato scoperto. Fu addirittura il primo a farne un mappamondo. Per farlo, il geniale artista italiano del Rinascimento utilizzò due gusci inferiori di due uova di struzzo.

Queste uova provenivano da struzzi del giardino del castello di Pavia. Il suo mappamondo è il più antico della storia su cui sono incisi i nomi di molti Paesi, tra cui Brasile, Giudea, Cina, Germania, ecc. Questa storia è stata pubblicata da Cambridge Scholars Publishing nel 2018 nel mio libro “The da Vinci Globe”, altamente consigliato a tutti i lettori che vogliono seguire un'indagine appassionante.

Nel 2018, non avendo ancora in programma di scrivere sul cinquecentenario di Verrazzano, ho scritto del fratello di Verrazzano la cui mappa è conservata ai Musei Vaticani. Avevo ispezionato questa mappa. Avevo notato il suo errato e mitico Mare Verrazzaniano, che collega uno stretto istmo sull'Oceano Atlantico con il Pacifico. Sul Globo da Vinci è raffigurato un passaggio marittimo aperto verso la costa orientale dell'Asia.

Nel Codice Atlantico, pagina 331 recto, risalente al 1504, Leonardo scrive "El mio mappamondo che ha Giovanni Benci". Il diametro terrestre di 7.000 miglia indicato da Leonardo si riflette nella scala del Globo da Vinci, pari a 1/80.000.000. Il miglio nautico italiano da lui utilizzato è di 1.280 metri per miglio. La definizione di Leonardo permette di fare un confronto con quanto scritto da Verrazzano in miglia per quanto riguarda la circonferenza del mondo sul 34° parallelo nord.

La fortuna vuole che ci sia un collegamento fisico e storico tra il luogo di conservazione del documento del 1524 e la scoperta letteraria di New York, il primo atto di nascita cartografico con la prima denominazione in assoluto dell'America, risalente al 1507 circa, e con il gemello del Globo da Vinci del 1504.

L'aspetto piuttosto unico al mondo è che il Dipartimento dei libri rari della New York Public Library, che ospita il Lenox Globe del 1504, un globo fuso in rame, senza patina verde o nera, replica del globo da Vinci, possiede anche l'epico certificato di nascita cartografico degli Stati Uniti, risalente al 1507 circa.

La Pierpont Morgan Library ospita invece lo storico certificato letterario di nascita di New York di Verrazzano, risalente al 1524, con informazioni sulle dimensioni del mondo basate sul Globo da Vinci.

Entrambe le biblioteche si trovano a Manhattan. Si trovano a soli cinque isolati e a un angolo di strada l'una dall'altra, ovvero Madison Avenue/E 41 Street, e nessuno sembra (ancora) aver notato questi preziosi tesori storici americani.

Ora che il suo libro è stato pubblicato, quali sono le conclusioni a cui è giunto riguardo a questo evento storico che ha visto protagoniste, 500 anni fa, le terre che sarebbero poi diventate l'Italia e gli Stati Uniti?

Il mio nuovo libro, disponibile su www.cambridgescholars.com, svela per la prima volta nella storia i retroscena e il significato più profondo della scelta dei nomi dei luoghi da parte di Verrazzano. In passato questi non sono stati compresi correttamente. Il suo diario di viaggio è molto più di un resoconto. È la testimonianza personale di un italiano che ha scoperto gran parte della costa orientale degli Stati Uniti. I nomi dei luoghi geografici, riportati da Verrazzano, possono essere collegati alla sua esperienza di navigatore, al suo contesto sociale e all'ambientazione della sua vita.

Si è ritenuto che Verrazzano, pioniere della globalizzazione, abbia dato ai luoghi nomi di alberi e piante, identificati in modo impreciso come dovuti a un interesse botanico. Tuttavia, offro la prova che il loro significato simbolico, compresa la connotazione religiosa, che rientra nell'iconografia rinascimentale, avrebbe dovuto essere preso in considerazione. Si può ipotizzare che Verrazzano sia stato in Francia diversi anni prima del 1521. Molto probabilmente Verrazzano cercò un nuovo datore di lavoro in Francia nel 1518 con le conoscenze cartografiche aggiornate che aveva raccolto a Lisbona e a Siviglia.

A dare un'idea delle informazioni cartografiche che Verrazzano potrebbe aver appreso durante il suo soggiorno a Lisbona e Siviglia nel 1517 è un piccolo mappamondo basato su un disegno di Leonardo da Vinci. È degno di nota un foglio poco appariscente di mappamondi trovato tra le carte scritte a mano da Leonardo.

Il motivo per cui questi, risalenti al 1515 circa, sono rilevanti è che sono gli unici contemporanei a raffigurare la Florida come isola, scoperta nel 1513, e la via marittima occidentale aperta sul 34° parallelo nord tra la Florida e Bacalar (Terranova). Verrazzano scelse questa presunta via di mare aperta per la sua audace impresa del 1524, cercando di raggiungere il Catai (Cina).

Al suo datore di lavoro reale, Verrazzano apparve come un umanista diplomatico, cortese ed erudito. La sua conoscenza delle Sacre Scritture è notevole. Questo "astronauta" toscano del primo Cinquecento ricorda personaggi come Pierrevive e Giovio, non per la loro importanza religiosa o militare, ma per il loro intelletto e la loro influenza culturale nella società.

Gli antichi hanno un ruolo nel discorso di Verrazzano. Sebbene Verrazzano corregga Aristotele e Tolomeo e faccia riferimento ad altri antichi, tra cui l'Arcadia di Virgilio, il calcolo dell'italiano della dimensione del mondo è tipico del Rinascimento.

Con questo studio, Verrazzano può ora essere ricordato, tra le tante cose, come lo scopritore di New York. La sua fu la prima esplorazione della costa orientale degli Stati Uniti nella prima età moderna. Verrazzano è un'ispirazione per molti italiani nel Nuovo Mondo fino ad oggi. Un segno del fatto che Verrazzano è molto amato negli Stati Uniti è che tutti conoscono il grande ponte di New York che porta il suo nome.

Lei è un collezionista di mappe e globi antichi e membro di diverse istituzioni riconosciute a livello mondiale, tra cui la Washington Map Society, la Leonardo da Vinci Society, la International Society for the History of the Map. Nessuno tra le persone che conosco ha maggiori conoscenze per rispondere a quest'ultima domanda, che si applica a qualsiasi evento accaduto o persona vissuta 500 anni fa (ogni riferimento a Cristoforo Colombo non è affatto casuale). Ha senso, è corretto, è onesto, pretendere e obbligare gli altri a giudicare il mondo di cinque secoli fa con la mentalità, i principi e gli atteggiamenti di oggi?

La ringrazio per il suo gentile complimento. Penso che sia uno sviluppo naturale, in gran parte influenzato dai media. Le persone interpretano la storia attraverso gli occhiali con cui guardano la televisione e i film ogni giorno, e forse anche quando leggono i giornali. È importante imparare la storia per conoscere il futuro. Credo che un detto dica che la storia si ripete. Le mappe e i mappamondi antichi contengono molte conoscenze geografiche importanti. Esse riflettono l'interpretazione storica dell'epoca in cui sono state realizzate e di quella precedente. Non tutte sono sempre aggiornate, ma forniscono un quadro delle influenze nazionali e dei confini storici. Aiutano a comprendere meglio la situazione contemporanea di molti Paesi del mondo. Il modo in cui la storia e la sua educazione vengono gestite nella comunità è un indicatore del valore della storia. Non ha senso cercare di reinterpretare la storia con i valori di oggi. Questa timida reinterpretazione può preannunciare l'evoluzione della società.

Nel diario di viaggio italiano di Verrazzano, il Codice Cèllere, un documento fondamentale per la storia dell'America, Verrazzano descrive ciò che il re di Francia gli chiese di fare: trovare la via marittima per la Cina. L'impresa del toscano - come navigatore vittorioso che ce l'ha fatta con il suo equipaggio e ha attraversato le sconosciute acque oceaniche con una sola nave - è stata la prima nella storia.

Meno di un secolo dopo, nel 1607, la Baia di Chesapeake sarebbe stata il punto di ingresso per gli immigrati inglesi e per i loro insediamenti di successo ai confini del fiume James a Jamestown, in Virginia. Sospetto che molte persone non abbiano mai sentito parlare di Verrazzano né del suo diario di viaggio e delle sue vivide descrizioni. Il libro che ho scritto serve a far conoscere meglio la sua storia americana e lui. È più di una semplice ripetizione delle descrizioni. Offre al lettore una prospettiva unica per comprendere meglio il contesto storico di Verrazzano e il suo background. Pertanto, ha più senso imparare a valutare storicamente il mondo di cinque secoli fa e, di conseguenza, comprendere il pensiero, i principi e gli atteggiamenti del tempo passato per capire meglio il presente.

Per coincidenza, il magistrale monumento in bronzo di Giovanni da Verrazzano del 1909, realizzato da Ettore Ximenes (1855-1926) nel Battery Park di New York, poggia su un piedistallo del 1952. È realizzato in granito prelevato dall'Isola dei Cervi, una delle tre isole che portano il nome delle principesse navarresi a cui il toscano fa riferimento nel suo diario di viaggio.

In altre parole, l'esploratore italiano si trova ora su una pietra legata alle tre isole delle principesse di Navarra nominate proprio da Giovanni da Verrazzano. Una di queste isole si chiama oggi Isola dei Cervi, sulla costa del Maine. Credo che questo sia avvenuto per caso. Ci si può chiedere se questo sia importante. Direi di no. Ma forse gli studiosi americani che in seguito visiteranno Battery Park a New York impareranno che la storia di Verrazzano, vecchia di 500 anni, è intimamente legata a quella dell'America di oggi, senza essere inutilmente reinterpretata con i valori del XXI secolo. La pietra centenaria dell'Isola dei Cervi ne è la prova.

Facendo un'eccezione, concludo questa intervista con una considerazione personale, attribuibile solo a me, Umberto Mucci, e non al Professor Missinne. Nel 1528, durante la sua terza spedizione, Verrazzano fu catturato e divorato (sì, divorato) da una tribù di cannibali. Con il massimo rispetto e la totale solidarietà ai nativi americani per tutto il male che è stato fatto loro (non da Colombo), la prossima volta che sentite qualcuno descrivere Cristoforo Colombo come il cattivo della storia che arriva in un presunto paradiso terrestre pacifico e meraviglioso, e porta il male tra indigeni premurosi, felici e gentili gli uni con gli altri, ricordategli della fine che ha fatto questa altro eccezionale esploratore, in quello che era tutto tranne che un paradiso terrestre di pace e prosperità.