Here at We the Italians we’ve been thinking that science and research are two fundamental and very delicate aspects of our lives way before the covid-19 virus hit the whole world: here at We the Italians we believe that science and research are extremely serious and complicated things, that require studies, talent and sweat, and we are therefore grateful to scientists and researchers all over the world who must be protected, well paid and listened to, because there is no improvisation in their field.

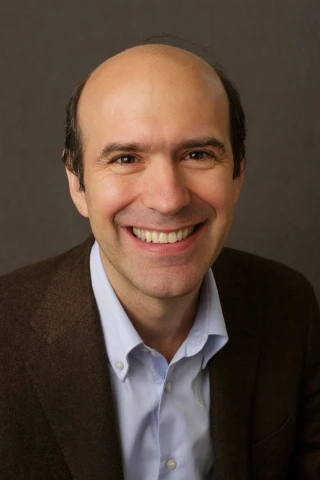

In this field, Italy excels and has always stood out: in the Italian DNA there is genius and talent, innovation and curiosity, resilience and stubborness. These qualities are recognized everywhere, and particularly in the United States: that's why ISSNAF, the Italian Scientist and Scholars in North America Foundation, is so important. We welcome on We the Italians the new president of this magnificent institution, Cinzia Zuffada.

President Zuffada, first of all, I would ask you to tell us a little bit about yourself: from Italy to the United States, what is your story?

I was born and grew up in Broni, a small town in the Oltrepo’ area in Lombardy to which I am very attached and that gave me a lot. I credit very much that environment for stimulating my early interest in science; my current research interest has to do with water, and the wet areas in the countryside are perfect for curiosity and experimentation, that gave freedom to my childhood; the environment gave me the opportunity for daily discoveries and inventions.

Regarding my student career, I was attracted to a large number of subjects and I certainly wanted to have the opportunity to get an education that was forward-looking, even if the world was a lot smaller than today. I saw education as an opportunity to socially elevate myself. I thought that with the engineering degree, I would have many paths open to me. I went to the University of Pavia and then was a researcher at Caltech, in California, for one year. My transition from Pavia to California was very shocking because I wasn’t prepared at all, at the time there were very few collaborations and certainly no institutional ones, so it was like jumping in the water without knowing how to swim.

I gradually built my experience, I grew from a professional point of view, then I ended up marrying and I settled into an environment that gave me many more opportunities than the place where I grew up. Since 1992, I have been with JPL (Jet Propulsion Laboratory), a federally-funded research and development laboratory in Los Angeles financed by NASA, whose mandate is to lead the robotic exploration of the solar system, including our planet, from space. We make measurements (and use sources) from space to study the earth through remote sensing, with a number of systems based on different technologies.

You are the new President of ISSNAF. We ask you to describe briefly the history, mission, and activities of this very important institution

ISSNAF, the Italian Scientist and Scholars in North America Foundation was founded in 2007, by a body of very distinguished Italians including Noble Prize winners. At the time, it was the only network of researchers covering of all North America. It gathered many of the most important Italian researchers in North America, spanning various generations, who wanted to come together and celebrate their Italian identity. Specifically, people born and educated in Italy, operating in the US and Canada, professionally established, wanting to maintain a sense of Italian identity alongside their transformed identity that the experience abroad had given them, and help the newcomers get established.

Over time, the leadership became disconnected from the membership, we experienced a decline of resources and the loss of our executive-Director Monica Veronesi; she was a great person who passed away prematurely.

So, a group of us who had joined ISSNAF leadership relatively recently, in the past two years worked very actively to relaunch and renew the foundation; today ISSNAF is a younger organization, with a new cadre of leaders and extension of its charter. We want to emphasize the identity through the empowerment of the community and the celebration of talent, not only of those who have done extremely well professionally, but also the talent of the new generation that has come to North America more recently than I in a completely different situation, providing more structured services and benefits to help them integrate into this new reality of work and life. Nowadays ISSNAF is no longer focused only on science and medicine, but it’s broader, open to more people from all disciplines, including social sciences, arts and economics.

You also have chapters, right?

Several Local and Thematic Chapters were founded in prior years but today most of them are not active anymore because the older generation didn’t do succession planning. We didn’t put in place a structure to cultivate the newer generations and entrain them, so in some cases the interest waned when specific people moved on. So, it’s our job now in this administration to restart those efforts and structure them, introducing a process to rotate the cadre periodically. The way we see is that the turnover in the leadership must be high by design, to improve the rotation: a little bit like what happens in professional societies. The terms should be very well defined, two or three years and then there is a rotation and rejuvenation. That’s exactly how I would like to see the network of chapters evolve in the future.

Every year in November ISSNAF awards a series of prizes during a ceremony held at the Italian Embassy in Washington. In the hope that the ceremony can be organized again this year, can you tell us more about these awards?

ISSNAF has historically had programs for awards to young investigators, “the young ISSNAF awards”: they recognize research accomplishments in the early stage of their career. This year there are four awards, including a brand new one, the “Italian Embassy Award”, that will go in 2020 to an Italian researcher in the US whose research is showing potential for an impact on the fight and cure of COVID 19.

The Embassy will be involved obviously with the selection process. It adds to other awards that we have, named for our sponsors, such as the Paola Campese Award for research in leukemia, the Franco Strazzabosco Award for research in engineering, and the Mario Gerla Award for research in computer science. These are Italian families who named an award in memory of their loved ones: it’s a tradition that we want to grow, so we are looking to increase this type of awards that underline the involvement of very specific people, whose memories are kept alive by recognizing the younger generation in one or more field of research.

There has been a call which came out at the beginning of May end ended a few days ago. There will be a rigorous selection based on materials in their application; this year we also require two references who can speak about the contributions of the candidate to their field.

It’s not clear whether this year we will have an event at the Embassy; it’s too early to tell, but we are studying something that would be equally exciting. It’s possible that once we down select the finalists, we can have webinar sessions with the candidates giving their presentations to a remote jury. We may have the Italian Consulates of the winners join us to present the award, maybe with a meeting that can be arranged more simply and more compatibly with the in-person interaction requirements that we could have at that time. This could be even more important for the profile of the people awarded, because the local Consulates would be able to appreciate who they have in their community. They would become better known in their local reality, which is a good thing: that doesn’t mean that the Embassy will not participate, of course they will continue to work very closely with ISSNAF, like we did for example in the GoFundMe fundraising campaign. But this could be an additional example on how we want to connect more closely with the local environments also.

Please tell us more about the fundraising

The Embassy wanted to organize a fundraising activity that involved the entire US territory, to shine a light on the dramatic situation of COVID 19 in Italy. The funds were destined to three Italian hospitals at the forefront of the fight. In this fight there is of course the action of stopping the disease and helping the people who are infected, but there’s also the need to do research to prevent or reduce infections. That’s why we chose these institutions: the Spallanzani Hospital in Rome, the Sacco Hospital in Milan, and the Cotugno Hospital in Naples. There are high profile researchers that work in Italy at these institutions, and the Embassy was gracious to select us as their partner.

We were honored to support the Embassy and help promote this initiative, through our contacts and our channels, with the research communities that we can reach. The fundraising turned out to be successful, also raising the visibility of research communities, in both continents, who might be already working together. We have examples of people joining studies, or working on research together. That’s the nature of research. It was already happening even before COVID 19.

Obviously, the coronavirus has brought radical changes in this as well: what is your goal for your term as President of ISSNAF?

I think that the first goal is to get us on more solid ground in terms of the infrastructure, in particular IT infrastructure to communicate to our membership and to our network of volunteers and people that work for the organization. This has been a problem in the past. We just launched our new website https://www.issnaf.org.

We had an Executive Director when the funds allowed it. We need to put in play a layer of people who can support us operationally. Eventually we will have more resources to allow us to hire people to work for us, as a non profit corporation. At the moment we are not there yet. So, I thank We the Italians for this opportunity you are giving me to make a call to volunteer for ISSNAF. It’s a way to connect, it’s also a way to gain experience. For example, we need to build and support an IT infrastructure that allows us to gather information, organize data, cultivate and monitor membership, so there is an opportunity for somebody who has these interests and time to work with us on this topic, or with our social media.

Another component is the cultivation of donors, which needs to be strengthened to allow revenues to keep coming. At present we run the organization solely with a few of us, working a lot outside business hours, also at nights, based on our limited funds. So, we rely on donations from our board members and individual supporters, and right now these are our sources of revenues. We need to extend our pool of donors to include industry and other organizations to survive.

Is there a complete database of Italian researchers in North America?

We don’t have a complete list of researchers, because our lists haven’t been updated in the last few years. We have over three thousand people in our current list, but we probably have very easily in North America a factor of ten as many people who are part of the intellectual diaspora that ISSNAF looks to connect. The potentials are very high, it depends on whether they are interested in being connected with us, because we go beyond the connections of other professional societies, that typically focus on one discipline. In our case, we want to be connected with other Italians of similar background and experience, to provide a way of highlighting and sharing, outside of our single disciplines, the work that this community has been doing.

The pandemic has highlighted even more the fundamental importance of research and science, which are the very subjects that link together the members of ISSNAF. Among the many Italian researchers and scientists who are part of the institution that you lead, is there any story that you would like to tell our readers?

It’s difficult to choose, because there are lots of stories. For example, there are several people who have been honored with our ISSNAF awards at the stage when they were assistant professors, at the beginning of their academic career. Getting an ISSNAF award has helped them acquire more prominence.

I remember the story of Simona Bordoni who got an ISSNAF award in 2014. At that time she was starting as a professor at Caltech, California Institute of Technology. So, Simona got this award in Environmental Sciences, and Caltech university had the news of her award on their webpage. Simona went on to become a tenured faculty. Now she has left Caltech and returned to Italy, so that’s a great story in itself because she was successful, did well, then later on for whatever reasons she ended up having an academic position at the University of Trento.

That’s just one example, but there are others: Marco Pavone used to be at NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory in robotics and he is now a professor at Stanford University. He also won the ISSNAF award, and two years ago he subsequently won the “Young Investigator Presidential Award”.

We also have success stories coming from the people who come to us looking for a mentor. One that I have become very recently aware of is somebody who reached out and was mentored by one of the members of our Scientific Council, which is made of highly accomplished researchers. Our Council member is Filippo Mancia, a professor at Columbia University. He mentored a young researcher, Pietro Stroppia, who wanted to become an academic in the US; through mentorship over time, he was able to submit progressively stronger applications, and now he has got an assistant professorship. In that case, the mentoring was very helpful: it allowed the young researcher to learn the nuances and navigate an environment that for him was rather difficult to understand at first.

The new emigration from Italy to the United States is very different from that of more than 100 years ago. Many students, researchers, and professionals in different fields of science spend a period in the United States, and some of them end up staying there. What do they bring that is different, typically "Italian", compared to their colleagues from all over the world they meet in America?

First, for people who come at the early stage of their career, there is their forma mentis due to the Italian education, which provides a very good foundation, recognized not just in North America, but also in Europe. More and more Italian students are spending time abroad, during their education, and this is a very good set up: their identity becomes an important component of this multifaceted and multicultural world that we are living in. We are an important component because our culture is very strong, thinking about the many things we have provided to the rest of the world. In a sense, being Italian is an attractant for people who want to penetrate our culture; lots of people from any other place want to mingle with Italian people, because they are fascinated with Italy and Italian things that they know. This is possibly a quite important component that young Italians can immediately bring to their new environment.

I also want to say that, unlike in my generation or earlier, we see now much more collaboration between Italian and American universities. We were much more isolated: now we have interactions, shared programs, there is a pattern of bringing Italian know-how to North America. It goes beyond the individual, today.

How is the state of scientific collaboration between Italy and the United States? And what can Italy do to improve it?

I cannot speak for all fields: in my field, from the standpoint of scientific collaboration, at the institutional level the collaboration is very strong. For example, Italy has had a strong presence in space for a very long time; so the Italian Space Agency has a strong role in Europe and as a partner to the US, in the relationship with NASA.

Unfortunately, Italy has so far done very little to encourage Italian scientists and researchers to return to work in Italy. Do you have any advice in this sense to forward to Italian institutions?

My advice would be to create opportunities for people to return, and I mean very flexible things because it might not necessarily be that somebody returns permanently for work. It’s possible that people from North America might be able to go back to Italy and maintain a situation where they work in both parts of the world. Certain universities ought to be able to operate like this, but they need to give up the rigidity they sometimes show: introducing some flexibility might be advantageous.

You were recently the protagonist of a webinar entitled "Reflections on the earth as seen from space". We ask you to tell our readers, instead, what Italy is like as seen from the United States

It’s a very broad question and there are many views. I don’t want to talk about stereotypes because I’m sure that’s not what you’re asking me. In terms of looking at Italy as a partner, as a source of intellectual wealth, I think we all recognize that there are lots of Italian people who are very good. I guess we all would like for the system, as I said before, to be more flexible: there is a sort of an impenetrable layer, so that’s probably the type of change that one would like to see first. It’s very difficult, for example, for entrepreneurs to be able to come to Italy and start activities. I think that the true desire on the part of all communities, not just the Italians in North America, is that they would all love to be able to engage more with Italy, and it’s just not easy. I hope that by developing generations of Italian people who know what things are like outside of Italy, and have learned of possible different approaches, Italy might be able eventually to create and evolve also a generation of people in power that can make changes. This generation needs to be allowed to walk the corridors of power, needs to be able to have a voice: so I hope that these times of crisis can also be times of opportunity, for these voices to be heard. That would be a starting point.

Per come la pensiamo qui a We the Italians, la scienza e la ricerca erano due aspetti importantissimi e delicati della nostra vita anche prima che arrivasse il virus che ha colpito il mondo intero: noi di We the Italians crediamo che scienza e ricerca siano cose estremamente serie e complicate, da affrontare con studi, talento e sudore, e siamo pertanto grati agli scienziati e ai ricercatori di tutto il mondo che vanno protetti, ben pagati ed ascoltati, perché non esiste improvvisazione nel loro campo.

In questo campo, l'Italia eccelle e si distingue da sempre: nel dna italiano c'è il genio e il talento, l'innovazione e la curiosità, la resilienza e la caparbietà. Queste qualità ci sono riconosciute ovunque, e in particolare negli Stati Uniti: è per questo che è così importante ISSNAF, the Italian Scientist and Scholars in North America Foundation. Siamo il benvenuto su We the Italians al nuovo presidente di questa magnifica istituzione, Cinzia Zuffada.

Presidente Zuffada, prima di tutto le chiedo di raccontarci un po' di lei: dall'Italia agli Stati Uniti, qual è la sua storia?

Sono nata e cresciuta a Broni, un piccolo paese dell'Oltrepò in Lombardia a cui sono molto legata e che mi ha dato molto. A quell'ambiente do molto credito per aver stimolato il mio precoce interesse per la scienza; il mio attuale interesse per la ricerca ha a che fare con l'acqua, e le zone umide della campagna sono perfette per la curiosità e la sperimentazione, che hanno dato libertà alla mia infanzia; l'ambiente mi ha dato l'opportunità di scoperte e invenzioni quotidiane.

Per quanto riguarda la mia carriera studentesca, ero attratta da un gran numero di materie e volevo certamente avere l'opportunità di avere un'educazione che fosse proiettata verso il futuro, anche se il mondo era molto più piccolo di oggi. Vedevo l'istruzione come un'opportunità per elevarmi socialmente. Pensavo che con la laurea in ingegneria avrei avuto molte strade aperte per me. Sono andata all'Università di Pavia e poi sono stata ricercatrice a Caltech, in California, per un anno. Il mio passaggio da Pavia alla California è stato molto scioccante perché non ero affatto preparata, all'epoca c'erano pochissime collaborazioni e sicuramente nessuna istituzionale, quindi era come tuffarsi in acqua senza saper nuotare.

Ho costruito gradualmente la mia esperienza, sono cresciuta dal punto di vista professionale, poi ho finito per sposarmi e mi sono sistemata in un ambiente che mi ha dato molte più opportunità del luogo in cui sono cresciuta. Dal 1992 faccio parte del JPL (Jet Propulsion Laboratory), un laboratorio di ricerca e sviluppo di Los Angeles finanziato dalla NASA, il cui mandato è quello di guidare l'esplorazione robotica del sistema solare, compreso il nostro pianeta, dallo spazio. Effettuiamo misurazioni (e utilizziamo fonti) dallo spazio per studiare la terra attraverso il telerilevamento, con una serie di sistemi basati su diverse tecnologie.

Lei è la nuova presidente dell'ISSNAF. Le chiediamo di descrivere brevemente la storia, la missione e le attività di questa importantissima istituzione

ISSNAF (Italian Scientist and Scholars in North America Foundation), la Fondazione degli scienziati e degli studiosi Italiani in Nord America, è stata fondata nel 2007, da un gruppo di italiani molto illustri, tra cui alcuni vincitori del Premio Nobel. All'epoca era l'unica rete di ricercatori che copriva tutto il Nord America. Riunì molti dei più importanti ricercatori italiani in quest’area, di varie generazioni, che volevano riunirsi e celebrare la loro identità italiana. In particolare, persone nate e formate in Italia, che operano negli Stati Uniti e in Canada, professionalmente affermate, desiderose di mantenere il senso dell'identità italiana accanto a quella trasformata che l'esperienza all'estero aveva dato loro, e di aiutare i nuovi arrivati ad affermarsi.

Con il tempo, la leadership si è scollegata dai soci, abbiamo vissuto un calo di risorse e la perdita della nostra direttrice esecutiva Monica Veronesi, una grande persona che purtroppo è prematuramente scomparsa.

Così, un gruppo di noi che era entrato a far parte della leadership di ISSNAF relativamente di recente, negli ultimi due anni ha lavorato molto attivamente per rilanciare e rinnovare la fondazione. Oggi ISSNAF è un'organizzazione più giovane, con un nuovo assetto nella leadership e l'estensione del suo statuto. Vogliamo sottolineare l'identità attraverso il potenziamento della comunità e la celebrazione del talento, non solo di coloro che hanno svolto un lavoro estremamente professionale, ma anche del talento della nuova generazione giunta in Nord America più recentemente di me in una situazione completamente diversa, fornendo servizi e benefici più strutturati per aiutarli ad integrarsi in questa nuova realtà di lavoro e di vita. Oggi ISSNAF non è più focalizzata solo sulla scienza e la medicina, ma è più ampia, aperta a più persone di tutte le discipline, comprese le scienze sociali, le arti e l'economia.

Avete anche diversi chapters, vero?

Negli anni precedenti sono stati fondati diversi chapters locali e tematici, ma oggi la maggior parte di essi non è più attiva perché la generazione più anziana non si occupava di pianificazione della successione. Non c’era più una struttura per coltivare le nuove generazioni e coinvolgerle, così in alcuni casi l'interesse è diminuito. Quindi è nostro compito ora, in questa amministrazione, far ripartire questi sforzi e strutturarli, introducendo un processo di rotazione periodica dei quadri. Il nostro modo di vedere è che il turnover nella leadership deve essere costante e rapido, per migliorare la rotazione: un po' come accade nelle società professionali. I termini dovrebbero essere molto ben definiti, due o tre anni e poi c'è una rotazione e un ringiovanimento. È proprio così che vorrei che la rete dei capitoli si evolvesse in futuro.

Ogni anno a novembre ISSNAF assegna una serie di premi nel corso di una cerimonia che si svolge presso l'Ambasciata d'Italia a Washington. Nella speranza che la cerimonia possa essere organizzata anche quest'anno, può dirci qualcosa di più su questi premi?

ISSNAF ha storicamente avuto programmi per i premi ai giovani ricercatori, chiamati “young ISSNAF awards”: essi riconoscono i risultati della ricerca nella fase iniziale della carriera dei premiati. Quest'anno i premi sono quattro, tra cui uno nuovo di zecca, il "Premio dell'Ambasciata Italiana", che andrà nel 2020 a un ricercatore italiano negli Stati Uniti il cui lavoro sta dimostrando di avere un potenziale impatto sulla lotta e la cura contro il covid-19.

L'Ambasciata sarà ovviamente coinvolta nel processo di selezione. Questo premio si aggiunge ad altri che abbiamo intitolato ai nostri sponsor, come il Premio Paola Campese per la ricerca sulla leucemia, il Premio Franco Strazzabosco per la ricerca in ingegneria e il Premio Mario Gerla per la ricerca in informatica. Si tratta di famiglie italiane che hanno intitolato un premio in memoria dei loro cari: è una tradizione che vogliamo far crescere, quindi cerchiamo di incrementare questo tipo di premi che sottolineano il coinvolgimento di persone molto specifiche, la cui memoria viene mantenuta viva riconoscendo il lavoro delle giovani generazioni in uno o più campi di ricerca.

C'è stata una call che è uscita all'inizio di fine maggio e si è conclusa pochi giorni fa. Ci sarà una rigorosa selezione in base ai materiali presenti nelle candidature; quest'anno richiediamo anche due referenze che possano parlare dei contributi del candidato al loro settore.

Non è chiaro se quest'anno avremo un evento in Ambasciata; è troppo presto per dirlo, ma stiamo studiando qualcosa che sarebbe altrettanto entusiasmante. È possibile che, una volta selezionati i finalisti, si svolgano sessioni di webinar con i candidati che presentano le loro candidature a una giuria remota. Potremmo chiedere ai Consolati italiani dei vincitori di unirsi a noi per presentare il premio, magari con un incontro che può essere organizzato in modo più semplice e più compatibile con le esigenze di interazione personale che potremmo avere in quel momento. Questo potrebbe essere ancora più importante per il profilo delle persone premiate, perché i Consolati locali sarebbero in grado di apprezzare chi hanno nella loro comunità. Diventerebbero più conosciuti nella loro realtà locale, il che è una buona cosa: ciò non significa che l'Ambasciata non parteciperà, naturalmente continueranno a lavorare a stretto contatto con ISSNAF, come abbiamo fatto ad esempio nella campagna di raccolta fondi su GoFundMe. Ma questo potrebbe essere un esempio in più di come vogliamo essere in contatto più stretto anche con gli ambienti locali.

Per favore, ci dica di più sulla raccolta fondi

L'Ambasciata ha voluto organizzare un'attività di raccolta fondi che coinvolgesse tutto il territorio statunitense, per far luce sulla drammatica situazione di covid-19 in Italia. I fondi sono stati destinati a tre ospedali italiani in prima linea nella lotta. In questa lotta c'è naturalmente l'azione di fermare la malattia e di aiutare le persone infette, ma c'è anche la necessità di fare ricerca per prevenire o ridurre le infezioni. Per questo abbiamo scelto queste istituzioni: l'Ospedale Spallanzani di Roma, l'Ospedale Sacco di Milano e l'Ospedale Cotugno di Napoli. In queste istituzioni ci sono ricercatori di alto profilo che lavorano in Italia e l'Ambasciata ha avuto la cortesia di sceglierci come partner.

Siamo stati onorati di sostenere l'Ambasciata e di contribuire a promuovere questa iniziativa, attraverso i nostri contatti e i nostri canali, con le comunità di ricerca che possiamo raggiungere. La raccolta di fondi si è rivelata un successo, aumentando anche la visibilità delle comunità di ricerca, in entrambi i continenti, che potrebbero già lavorare insieme. Abbiamo esempi di persone che si sono unite a studi o che lavorano insieme alla ricerca. Questa è la natura della ricerca. Era già successo anche prima di covid-19.

Ovviamente, il coronavirus ha portato cambiamenti radicali anche in questo: qual è il suo obiettivo per il suo mandato di Presidente dell'ISSNAF?

Penso che il primo obiettivo sia quello di portarci su un terreno più solido in termini di infrastrutture, in particolare infrastrutture informatiche per comunicare ai nostri soci e alla nostra rete di volontari e a persone che lavorano per l'organizzazione. Questo è stato un problema in passato. Abbiamo appena lanciato il nostro nuovo sito web

https://www.issnaf.org.

Avevamo un direttore esecutivo quando i fondi lo permettevano. Dobbiamo mettere in gioco un livello di persone che possano sostenerci operativamente. Alla fine avremo più risorse per permetterci di assumere persone che lavorino per noi, come ente senza scopo di lucro. Al momento non ci siamo ancora. Quindi, ringrazio We the Italians per questa opportunità che ci dà per sollecitare i lettori ad impegnarsi come volontari per ISSNAF. È un modo per connettersi, è anche un modo per fare esperienza. Per esempio, dobbiamo costruire e sostenere un'infrastruttura informatica che ci permetta di raccogliere informazioni, organizzare i dati, coltivare e monitorare le adesioni, quindi c'è l'opportunità per qualcuno che ha questi interessi e questo tempo di lavorare con noi su questo argomento, o con i nostri social media.

Un'altra componente è dato dai rapporti con i donatori, che deve essere rafforzato per consentire alle entrate di continuare ad arrivare. Attualmente gestiamo l'organizzazione solo con pochi di noi, lavorando molto al di fuori dell'orario di lavoro, anche di notte, sulla base dei nostri limitati fondi. Per questo motivo, ci affidiamo alle donazioni dei membri del nostro board e dei singoli sostenitori, e al momento queste sono le nostre fonti di reddito. Per sopravvivere, dobbiamo ampliare il nostro pool di donatori per includere le imprese e altre organizzazioni.

Esiste un database completo dei ricercatori italiani in Nord America?

Non abbiamo un elenco completo dei ricercatori, perché le nostre liste non sono state aggiornate negli ultimi anni. Abbiamo più di tremila persone nella nostra lista attuale, ma probabilmente il bacino dei protagonisti di questa diaspora intellettuale che ISSNAF cerca di collegare insieme è formato in Nord America da un numero di persone almeno dieci volte tanto. Le potenzialità sono molto elevate, dipende dal loro interesse ad essere collegati con noi, perché andiamo oltre le connessioni di altre società professionali, che tipicamente si concentrano su una singola disciplina. Nel nostro caso, vogliamo essere collegati con altri italiani che hanno simili formazione ed esperienza, per fornire un modo di evidenziare e condividere, al di fuori delle nostre singole discipline, il lavoro che questa comunità sta svolgendo.

La pandemia ha evidenziato ancora di più l'importanza fondamentale della ricerca e della scienza, che sono gli stessi soggetti che legano tra loro i membri di ISSNAF. Tra i tanti ricercatori e scienziati italiani che fanno parte dell'istituzione che lei dirige, c'è una storia che vorrebbe raccontare ai nostri lettori?

È difficile scegliere, perché le storie sono tante. Ad esempio, ci sono diverse persone che sono state premiate con i nostri riconoscimenti ISSNAF nella fase in cui erano professori assistenti, all'inizio della loro carriera accademica. Ottenere un premio ISSNAF li ha aiutati ad acquisire maggiore importanza.

Ricordo la storia di Simona Bordoni che ha ricevuto un premio ISSNAF nel 2014. A quel tempo stava iniziando come professoressa al Caltech, California Institute of Technology. Così, Simona ha ottenuto questo premio in Scienze Ambientali, e l'università di Caltech ha inserito la notizia del suo premio sulla loro pagina web. Simona è poi diventata una docente di ruolo. Ora ha lasciato Caltech ed è tornata in Italia, quindi è una grande storia in sé, perché ha avuto successo, ha fatto bene, poi in seguito è tornata in Italia e ora ha una posizione accademica all'Università di Trento.

Questo è solo un esempio, ma ce ne sono altri: Marco Pavone è stato al NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory in robotica ed è ora professore alla Stanford University. Anche lui ha vinto anche il premio ISSNAF e due anni fa ha vinto il "Young Investigator Presidential Award".

Abbiamo anche storie di successo che riguardano persone che vengono da noi in cerca di un mentore. Una di queste, che ho conosciuto di recente, è una persona che ha avuto come mentore uno dei membri del nostro Consiglio Scientifico, che è composto da ricercatori di alto livello. Il membro del nostro Consiglio è Filippo Mancia, professore alla Columbia University. Ha fatto da mentore a un giovane ricercatore, Pietro Stroppia, che voleva diventare un accademico negli Stati Uniti; attraverso il tutoraggio, nel tempo, ha potuto presentare domande sempre più qualificate, e ora ha ottenuto una cattedra di assistente. In questo caso, il mentoring è stato molto utile: ha permesso al giovane ricercatore di imparare le sfumature e di navigare in un ambiente che per lui all'inizio era piuttosto difficile da capire.

La nuova emigrazione dall'Italia verso gli Stati Uniti è molto diversa da quella di oltre 100 anni fa. Molti studenti, ricercatori e professionisti in diversi campi della scienza trascorrono un periodo negli Stati Uniti, e alcuni di loro finiscono per rimanervi. Cosa portano di diverso, tipicamente "italiano", rispetto ai colleghi di tutto il mondo che incontrano in America?

Innanzitutto, per le persone che arrivano all'inizio della loro carriera, c'è la loro forma mentis dovuta alla formazione italiana, che fornisce un'ottima base, riconosciuta non solo in Nord America, ma anche in Europa. Sempre più studenti italiani passano il loro tempo all'estero, durante la loro formazione, e questa è un'ottima impostazione: la loro identità diventa una componente importante di questo mondo sfaccettato e multiculturale in cui viviamo. Siamo una componente importante perché la nostra cultura è molto forte, pensando alle tante cose che abbiamo regalato al resto del mondo. In un certo senso, essere italiani è un'attrattiva per le persone che vogliono entrare nella nostra cultura; molte persone di qualsiasi altro luogo vogliono mescolarsi con gli italiani, perché sono affascinati dall'Italia e dalle cose italiane che conoscono. Questa è forse una componente molto importante che i giovani italiani possono portare immediatamente nel loro nuovo ambiente.

Voglio anche dire che, a differenza della mia generazione o di quella precedente, vediamo ora una collaborazione molto più intensa tra università italiane e americane. Eravamo molto più isolati: ora abbiamo interazioni, programmi condivisi, c'è un modello che porta il know-how italiano in Nord America. Oggi c’è un sistema che va oltre l’iniziativa del singolo individuo.

Com'è lo stato della collaborazione scientifica tra Italia e Stati Uniti? E cosa può fare l'Italia per migliorarla?

Non posso parlare per tutti i campi: nel mio campo, a livello istituzionale, la collaborazione scientifica è molto forte. Ad esempio, l'Italia ha una forte presenza nello spazio da molto tempo; così l'Agenzia Spaziale Italiana ha un ruolo forte in Europa e come partner degli Stati Uniti, nel rapporto con la NASA.

Purtroppo, l'Italia ha fatto finora molto poco per incoraggiare gli scienziati e i ricercatori italiani a tornare a lavorare in Italia. Ha qualche consiglio in questo senso da trasmettere alle istituzioni italiane?

Il mio consiglio sarebbe quello di creare opportunità di ritorno per le persone, e intendo cose molto flessibili, perché potrebbe non verificarsi necessariamente che qualcuno ritorni permanentemente per lavoro. È possibile che le persone dal Nord America possano tornare in Italia e mantenere una situazione in cui lavorano in entrambe le parti del mondo. Alcune università dovrebbero essere in grado di operare in questo modo, ma devono rinunciare alla rigidità che a volte mostrano: introdurre una certa flessibilità potrebbe essere vantaggioso.

Lei è stato recentemente protagonista di un webinar intitolato "Riflessioni sulla terra vista dallo spazio". Le chiediamo di raccontare ai nostri lettori, invece, com'è l'Italia vista dagli Stati Uniti

È una domanda molto ampia e ci sono molti punti di vista. Non voglio parlare di stereotipi perché sono sicuro che non è quello che mi sta chiedendo. Per quanto riguarda il guardare all'Italia come partner, come fonte di ricchezza intellettuale, credo che tutti noi riconosciamo che ci sono molte persone italiane che sono molto brave. Credo che tutti noi vorremmo che il sistema, come ho detto prima, fosse più flessibile: c'è una sorta di strato impenetrabile, quindi questo è probabilmente il tipo di cambiamento che si vorrebbe vedere prima. È molto difficile, ad esempio, che gli imprenditori possano andare in Italia per avviare un’attività. Credo che il vero desiderio di tutte le comunità, non solo degli italiani in Nord America, sia che tutti vorrebbero potersi impegnare di più con l'Italia, e non è facile. Spero che, sviluppando generazioni di italiani che sanno come stanno le cose al di fuori dell'Italia, e che hanno imparato a conoscere possibili approcci diversi, l'Italia possa eventualmente creare e far evolvere anche una generazione di persone al potere in grado di apportare cambiamenti. Questa generazione deve poter essere coinvolta nei ruoli in cui si ha potere, deve poter avere una voce: quindi spero che questi tempi di crisi possano essere anche tempi di opportunità, che queste voci siano ascoltate. Questo sarebbe un buon punto di partenza.