A few days ago, during the inauguration of the new President of the United States in Washington DC, there was a moment when the whole world rediscovered, if ever there was a need, the power of poetry. It was when 22 years old Amanda Gorman, the first person to be named National Youth Poet Laureate, delivered her beautiful poem "The Hill We Climb".

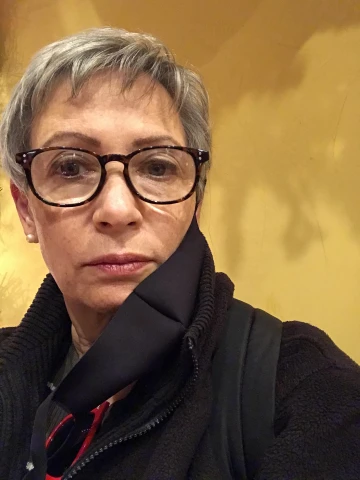

2021 is also the year that Italy dedicates to the greatest poet in the history of mankind, Dante Alighieri, whom we in Italy call “il sommo poeta” ("the supreme poet"). And it is also for this reason that, in our search for successful excellences of Italian origin in all fields of American society, today we are particularly happy and proud to host a beautiful person, a magnificent poet, Maria Lisella. Welcome to We the Italians, Maestra!

Maria, please tell us a little bit about yourself. Where were you born and raised?

I was born and raised in Jamaica, Queens, New York. Growing up in an African American and Caribbean neighborhood afforded me a certain liberty that other Italian Americans living in white suburban enclaves may not have known: there, I could be Italian-ish unself-consciously – I could eat my garlicky foods, I could speak a foreign language, I did not think about not being “white enough or American enough.”

Our household was a babble of Italian, Calabrese and English. I learned dialect orally, never wrote or read Italian until I went to Italy as a college student, which was a turning point in my life.

Once we moved to an all-White neighborhood, I discovered racism: we were called guineas and spics, they used the N-word. Most of the kids in the new neighborhood had never met a Black person or a Puerto Rican but had assumptions about them.

My late husband and I wrote essays about these dynamics in What Does It Mean to Be White in America and in Italian Canadiana, the AICW Conference Anthology of the Conference in Padula, Italy, held on August 2016.

What part of Italy are you from?

Most of my family is from Reggio and Cosenza in Calabria and Sepino in the province of Campobasso, Molise; one cousin lives in the Val d’Aosta. I have since discovered that both sides of my family were Jewish before the Spanish Inquisition when Calabria was almost 50% Jewish. I wrote about this in the Jerusalem Post.

My husband’s family came from Lanciano in Chieti province, Abruzzo and Capo d’Orlando in the Messina province in Sicily.

The Academy of American Poets has recently selected you as a 2020 Poet Laureate Fellow, and you will spend the fellowship hosting a curated series of readings and writing workshops for senior citizens in Queens, New York. A lot of Italians live there…

My workshops are designed for underserved senior communities. I’ve developed a series for SAGE, the advocacy group for gay seniors under the auspices of the Teachers & Writers Collaborative; for the Greater Astoria Historical Society; The Isamu Noguchi Museum and an ongoing series with the Queens Library opened to all seniors.

It would be fun to approach Italian social clubs for instance, so if you have any links to them, I would appreciate if you would share.

I know that your italianità in New York is not limited to the Queens neighborhood or just to poetry, right?

When I dated my late husband, Gil Fagiani, he and I were very much interested in integrating our Italian American sensibility with our progressive politics. More recently, we co-founded the Vito Marcantonio Forum, an educational organization dedicated to perpetuating the historic memory and significance of the most electorally successful progressive Congressman in American history - Vito Marcantonio.

In 1998, Distinguished Professor Phil Cannistraro and other academics, activists such as myself and my husband, helped produce a three-day conference at CUNY entitled The Lost World of Italian-American Radicalism: Labor, Politics, and Culture. That event showcased scholars from Italy and the US, spurring conversations on both sides of the Atlantic.

My husband is buried in Historic Woodlawn Cemetery near his two heroes: Fiorello La Guardia and Vito Marcantonio.

The Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition is also a progressive initiative I am involved in: its mission is to establish a memorial to the victims of the Triangle Fire that took 146 lives of young immigrants - and to keep us aware of the need for fair labor practices such as the need to raise the minimum wage. Until the destruction of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, the Triangle Shirtwaist fire was considered the deadliest workplace disaster in New York City and had a profound influence on building codes, and labor laws and by extension, OSHA regulations.

Also, you are the Queens Poet Laureate, the first Italian American to have this honor. What does it mean and how does it feel?

I was over the moon at the appointment: to be recognized in your own home is a gift. The position has afforded me access to people I would never meet otherwise and a chance to share my work with those who might not be on the literary circuit, thus giving me a chance to turn people on to poetry. The most important ingredient is access to poetry.

The Queens Library circuit has provided me with venues in every neighborhood in Queens where I have run readings and my current workshop series has been really well attended, which is very gratifying.

The duties of the poet laureate are not specific, and the position includes no office or salary, but it has been a jumping off point to reach out to Queens’ citizens through the library system through events such as readings, poetry contests, a bilingual series with my late husband at a local bookstore; and at a wide array of venues.

One of the biggest accomplishments was the Summer Poetry Contest that we conducted through the 65 branches of the Queens Library. That initiative drew more than 200 submissions each summer of work by people from children to adults. It was thrilling to see and hear Winners and Finalists read at the Flushing Library as their parents and families from all over the world filed in to witness their accomplishment. Most were first generation Americans, making the experience even more significant.

You are the co-curator of the Italian American Writers Association literary series. Please describe this wonderful initiative

IAWA was born out of the Yusuf Hawkins murder in Bensonhurst in 1989; it was in part a response to the fact that the media focused only on the most malignant and racist Italian Americans, a gesture that actually maligned all Italian Americans.

Unfortunately, it was indeed Italian American youth who attacked Hawkins and the incident became a watershed for Italian American authors and the intelligentsia to deliberately gain visibility in the media to counter the idea that all Italian Americans were ignorant and racist.

The late Professor Robert Viscusi of Brooklyn College called a meeting of Italian American authors and went around the room asking them: “Who is your favorite Italian American author other than yourself”? He recalled this anecdote often: “You could hear a pin drop.”

For him, this illustrated that Italian Americans writers were not paying attention, not reading or listening to each other. Thus the three initial rules of IAWA are: 1) Read each other, 2) Write or be written, 3) Buy our books, to which I have added 4) Review each other.

Many Italian American authors were present, but it was Viscusi and the recently deceased Vittoria Repetto whose dedication led to the reading series in 1991, made it the most democratic forum in our community as it features emerging and veteran authors who read their work out loud before an audience. It is a very affirming act to do so.

The series continued at the now defunct Cornelia St. Café with Vittoria Repetto until she started her own series at bluestocking’s bookstore. Viscusi asked my late husband and me to co-curate maybe 15 or 16 years ago. At one juncture, our schedule at Cornelia St. was curtailed and we organized readings at Sidewalk Café, both venues have since been the victims of the fiercely competitive and devastating real estate market in NYC.

We moved the readings to the New York Public Library - Mulberry St. branch, in the heart of Little Italy, a wonderful free space.

Three years ago, a second series began in Boston at I AM Bookstore curated by Julia Lisella and Jennifer Martelli. The bookstore has closed but its online business is flourishing.

Since the pandemic, the three of us have been co-curating monthly IAWA readings virtually. The series is 30 years old this year, and may well be one of the longest running literary series in New York and Boston.

You have three poets in your family, how does that work?

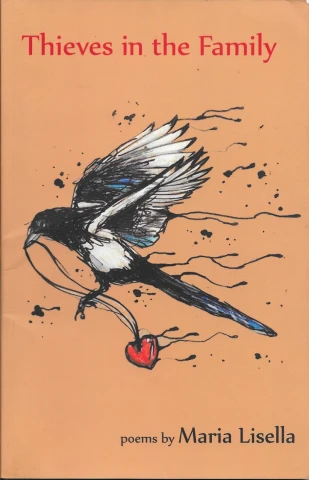

Yes, my sister Julia Lisella, and my late husband Gil Fagiani are poets and the delightful aspect of this is that when any of us achieves some success or publishing advance, it is as if all three of us have won that accomplishment.

I learn from both of them: all three of us observe the world through very different lenses, and have had very varied life experiences and education so while our voices move through a common ethnic filter, they are very distinct. Our work habits are also very varied, yet we are available to each other.

I lost my first editor when Gil died in 2018; we were the first readers of anything we both wrote and kept a folder called Scambio in the living room where we would each drop a new work in and the other would read it at their convenience and drop it back in with suggestions or edits. It was a great system that I miss greatly. Since my husband died, I shepherded his seventh book of poetry, Missing Madonnas, the third in his Connecticut trilogy and with the assistance of his mentor and friend Luigi Bonaffini, his bilingual collection is in the works. I have a chapbook that is pending publication and Gil and I were working on a collection together.

Italy has given birth to many poets and poets over the centuries. Why do you think Italians are drawn to poetry, art, and culture in such a rich way over the centuries?

I think of Italians and Italian Americans as expressive people – the early immigrants excelled in developing theater, so drama comes easily to us. By extension, I think of our community as being less afraid to express emotions and address real life events, personal and political.

We can see from the recent inaugural poem Amanda Gorman wrote and read that poetry is not a passive art or necessarily romantic, though it can be; it is very active and can incorporate current events in a way that can be understood.

Recently a writing prompt I wrote to was “Who or what inspired you to write?” Surprisingly, I credited my Calabrese grandmother, Filomena Calabro, with enriching my life with her own language and I believe poetry begins with just a love of language, sound, the puzzles you can solve, and the messages and stories you can tell.

Poetry is read at funerals, weddings, baptisms, moment of public, emotional significance. It can be a healing art in a sense, it can also stir the soul, revive old memories, in short, take you where you have not been before.

Within our community a few stand out in terms of influence. Maria Mazziotti Gillan, who has published more than 20 books of poetry and received many awards, has been a tremendous influence. As founder and Executive Director of the Poetry Center at Passaic County Community College in Paterson, NJ and editor of the Paterson Literary Review, Gillan was the right voice at the right moment: her work opened the gates for writers to emerge with their own identities and voices intact. Many other voices in our community like Maria Fama who are so very intimate with regional culture.

I would be remiss if I did not mention the increasing importance of translation: Luigi Bonaffini, Michael Palma have given us great translations of Dante, Mario Luzzi among many other Italian poets we might not access in the original language. The late Alfredo di Palchi who produced Chelsea literary magazine also supported the Bordighera Prize for many years that provided the winners with a translation of their work from English to Italian.

We the Italians serves as a way for Italy and the Italians who live here to better know and appreciate the wonderful Italian American community and its fantastic members. What can we do to help promote Italian poetry in the U.S. and Italian American poetry in Italy?

I am going to take a very sharp tone on this question: Italian Americans complain vociferously about stereotypes in the media, but they do not buy our books or support writers: our books are filled cover to cover with a plurality of characters who are not stereotypes. One of our distinguished scholars suggested to an important Italian American organization to buy our books and send one out with each new membership. The organization refused to do this because they claim to only support scientifically-based causes. Developing a tradition of cultural philanthropy tops the list of my wishes for the Italian American community.

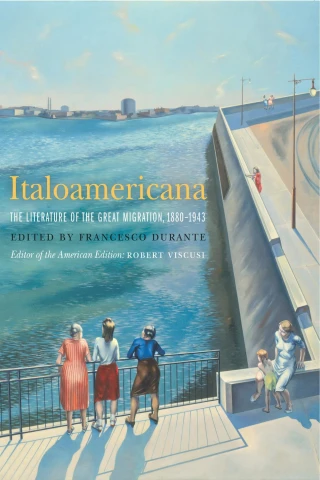

By contrast, an example of the community coming together to support an effort was the landmark translation and publication of ItaloAmericana (Fordham University Press), edited by the late Francesco Durante, Robert Viscusi, and Anthony Tamburri and entirely funded by Italian Americans.

Almost entirely translated by Italian Americans, this collection brings an English-speaking audience and a new generation face to face with these long inaccessible pieces: from poetry to drama to journalism, political advocacy, history, memoir, biography, and story. A must-have on your bookshelf.

And as a travel writer, I suggest traveling to your roots – where your relatives really came from - not just high-toned Italy of Rome, Florence and Venice, but the small, modest and sometimes forgotten or abandoned towns and villages - it is one of the most enriching experiences one can give oneself.

I have done presentations discussing how very important it is to Italian Americans to know who they really are – their backgrounds have much less to do with the Mona Lisa and the Medici than they do with village life, crafts, folktales, music, myths. Admittedly, most have lost their mother tongue, but studying Italian also enhances the culture and keeps our links to who we are very much alive. Further, Italian Americans need to enroll in Italian courses if they expect schools to add them to programs.

In a way, those who miss these opportunities are like cultural orphans – they are neither Italian nor American.

You are also a travel writer, and I imagine you have traveled a lot to Italy. What’s your favorite place in Italy? Is there a hidden gem only few Italian American probably know about, that you’d like to share with our readers?

This is a funny question because if there is a place I loved that much, I would want to keep it for myself. This is how I felt about Sicily the moment I visited on my honeymoon. Of course, Sicily is a place that would sooner or later be discovered. Years ago when I was giving a talk about Southern Italy to a group of travel agents, I gave a presentation about Sicily. Mario Perillo was in the audience at the time and jumped up and said, “Going to Sicily is like taking people to visit Alabama instead of the big sights.” His son Steve laughs at this because not much later, Perillo Tours developed programs to Sicily and they are among their best sellers.

I would also mention Calabria’s magnificent and unforgiving landscape and small mountain towns of Albidona or well-preserved borghi such as Morano Calabro, two places worth visiting, one with a view of the Ionian Sea. I was recently introduced to these locales when I took the Italian Diaspora course sponsored by the University of Calabria in 2019.

Every region of Italy has its incredible gems, it is truly one of the most multi-cultural destinations on the planet.

My work as a travel writer and editor has taken me to 60 countries in the past 20 or so years affording me incredible opportunities to not only meet people of different ethnic groups, which I already do at home in my own neighborhood, but meeting them in their home countries.

Much of my poetry are outtakes of articles in the words of guides, cooks, waiters or colleagues I have encountered across the globe. I try to give voice to their stories in my poetry.

I’ve asked this last question to many Italian Americans, but never to a poet. I would like to try to mix sacred and profane, high and low, if I may... I can't resist, I am going to ask: sauce or gravy?

My grandparents called it la salsa … gravy for us was brown and likely American, but my sisters remember my mother moving on to calling it gravy. And this is kind of funny because my Calabrese grandmother always accused my mother of trying to be more ‘merican like her Irish friends were. This led to a battle about my attending Catholic school because my grandmother insisted, the nuns being mostly Irish would not understand us. In a way she was right – my first public rebellion was correcting a nun who tried to anglicize my name to Marie or Mary. My father was called to the school and he miraculously defended my position, “Maria is a very easy name to pronounce in English and it is after all, the name of the Blessed Virgin”. Those nuns were the most educated women I knew, they lived without men in a communal society and they taught me how to read and write.

My after-school snack was not cookies and milk but a crusty piece of Italian bread dappled in golden olive oil, salt and oregano. The American kids said it looked like “bugs on bread,” but I knew better.

Qualche giorno fa, durante l'inaugurazione del nuovo Presidente degli Stati Uniti a Washington DC, c'è stato un momento in cui il mondo intero ha riscoperto, se mai ce ne fosse stato bisogno, il potere della poesia. E’ stato quando la 22enne Amanda Gorman, la prima persona ad essere nominata National Youth Poet Laureate, ha recitato la sua bellissima poesia "The Hill We Climb".

Il 2021 è anche l'anno che l'Italia dedica al più grande poeta della storia dell'umanità, Dante Alighieri, che noi in Italia chiamiamo "il sommo poeta". Ed è anche per questo che, nella nostra ricerca di eccellenze di successo di origine italiana in tutti i campi della società americana, oggi siamo particolarmente felici e orgogliosi di ospitare una bellissima persona, una magnifica poetessa, Maria Lisella. Benvenuta su We the Italians, Maestra!

Maria, raccontaci un po' di te. Dove sei nata e cresciuta?

Sono nata e cresciuta a Jamaica, Queens, New York. Crescere in un quartiere afroamericano e caraibico mi ha dato una certa libertà che altri italoamericani che vivevano in quartieri suburbani bianchi non avrebbero potuto conoscere: lì potevo essere inconsciamente italiana, potevo mangiare il mio cibo condito con l’aglio, potevo parlare una lingua straniera, non pensavo di non essere "abbastanza bianca o abbastanza americana".

Nela nostra famiglia si poteva sentire un misto di italiano, calabrese e inglese. Ho imparato il dialetto oralmente, non ho mai scritto o letto l'italiano fino a quando sono andata a studiare in Italia come universitaria, che è stato un punto di svolta nella mia vita.

Una volta che ci siamo trasferiti in un quartiere tutto bianco, ho scoperto il razzismo: ci chiamavano guineas e spics, usavano la N-word. La maggior parte dei ragazzi del nuovo quartiere non aveva mai incontrato un nero o un portoricano, ma pretendeva di sapere cose su di loro.

Il mio defunto marito ed io abbiamo scritto saggi su queste dinamiche in What Does It Mean to Be White in America e in Italian Canadiana, l'antologia della Conferenza AICW che si tenne a Padula, in Italia, dall'11 al 14 agosto 2016.

Da quale parte d'Italia vieni?

La maggior parte della mia famiglia è calabrese, di Reggio Calabria e Cosenza, e di Sepino in provincia di Campobasso, Molise; un cugino vive in Val d'Aosta. Da allora ho scoperto che entrambi i lati della mia famiglia erano ebrei prima dell'Inquisizione spagnola, quando la Calabria era quasi al 50% ebrea. Ne ho scritto sul Jerusalem Post.

La famiglia di mio marito veniva da Lanciano in provincia di Chieti, in Abruzzo e da Capo d'Orlando in provincia di Messina in Sicilia.

L'Academy of American Poets ti ha recentemente selezionata come Poet Laureate Fellow per il 2020, e tu terrai una serie di letture e laboratori di scrittura per anziani nel Queens, New York. Molti italiani vivono lì...

I miei workshop sono pensati per comunità di anziani poco servite. Ho sviluppato una serie per il SAGE, il gruppo di sostegno per gli anziani gay sotto gli auspici del Teachers & Writers Collaborative; per la Greater Astoria Historical Society; per l'Isamu Noguchi Museum e una serie in corso con la Queens Library aperta a tutti gli anziani.

Sarebbe divertente avvicinarsi anche ai club italiani, quindi se hai qualche link a questi, ti sarei grata se li condividessi.

So che la tua italianità a New York non è limitata al quartiere del Queens o solo alla poesia, giusto?

All’inizio della nostra relazione, io e il mio defunto marito, Gil Fagiani, eravamo molto interessati a integrare la nostra sensibilità italoamericana con la nostre idee progressiste. Più recentemente, abbiamo co-fondato il Vito Marcantonio Forum, un'organizzazione educativa dedicata a perpetuare la memoria storica e il significato del deputato progressista di maggior successo elettorale nella storia americana - Vito Marcantonio.

Nel 1998, l'illustre professor Phil Cannistraro e altri accademici, attivisti come me e mio marito, aiutarono a produrre una conferenza di tre giorni alla CUNY intitolata The Lost World of Italian-American Radicalism: Labor, Politics, and Culture. Quell'evento ha promosso studiosi dall'Italia e dagli Stati Uniti, stimolando conversazioni su entrambi i lati dell'Atlantico.

Mio marito è sepolto nel cimitero storico di Woodlawn vicino ai suoi due eroi: Fiorello La Guardia e Vito Marcantonio.

Anche la Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition è un'iniziativa progressista in cui sono coinvolta: la sua missione è quella di istituire un memoriale per le vittime del Triangle Fire, che uccise 146 giovani immigrate - e di tenerci consapevoli della necessità di pratiche di lavoro eque come la necessità di aumentare il salario minimo. Fino alla distruzione del World Trade Center l'11 settembre 2001, l'incendio del Triangle Shirtwaist era considerato il più mortale disastro sul posto di lavoro nella storia di New York e ha avuto una profonda influenza sui requisiti per le nuove costruzioni, e le leggi sul lavoro e per estensione, quelle sulla sicurezza.

Sei anche stata insignita del titolo di Queens Poet Laureate, la prima persona italoamericana ad avere questo onore. Cosa significa e come ci si sente?

Ero al settimo cielo per la nomina: essere riconosciuti in casa propria è un dono. La posizione mi ha dato accesso a persone che altrimenti non avrei mai incontrato e la possibilità di condividere il mio lavoro con coloro che potrebbero non essere nel circuito letterario, dandomi così la possibilità di avvicinare la gente alla poesia. L'ingrediente più importante è l'accesso alla poesia.

Il circuito della Queens Library mi ha fornito luoghi in ogni quartiere del Queens dove ho tenuto delle conferenze e la mia attuale serie di workshop è stata molto ben frequentata, il che è molto gratificante.

I doveri del Poet Laureate non sono specifici, e la posizione non include alcun ufficio o stipendio, ma è stato un punto di partenza per raggiungere i cittadini del Queens attraverso il sistema bibliotecario attraverso eventi come letture, concorsi di poesia, una serie bilingue con il mio defunto marito in una libreria locale e in una vasta gamma di luoghi.

Uno dei maggiori risultati è stato il concorso estivo di poesia che abbiamo condotto attraverso le 65 filiali della biblioteca del Queens. Quell'iniziativa ha attirato più di 200 candidature ogni estate di lavori di chiunque, dai bambini agli adulti. È stato emozionante vedere e sentire i vincitori e i finalisti leggere le loro poesie alla Flushing Library mentre i loro genitori e le loro famiglie da tutto il mondo si presentavano per testimoniare il loro successo. La maggior parte erano americani di prima generazione, rendendo l'esperienza ancora più significativa.

Sei la co-curatrice dell’Italian American Writers Association. Ci descrivi questa meravigliosa iniziativa?

IAWA è nata dopo l'omicidio di Yusuf Hawkins a Bensonhurst, New York nel 1989; è stata in parte una risposta al fatto che i media si concentravano solo sugli italoamericani più malevoli e razzisti, un gesto che in realtà diffamava tutti gli italoamericani.

Sfortunatamente, furono effettivamente alcuni giovani italoamericani ad attaccare Hawkins e l'incidente divenne uno spartiacque per gli autori italoamericani e l'intellighenzia: da quel momento poterono guadagnare visibilità nei media per contrastare l'idea che tutti gli italoamericani fossero ignoranti e razzisti.

Il defunto professor Robert Viscusi del Brooklyn College convocò una riunione di autori italoamericani e fece il giro della stanza chiedendo loro: "Chi è il vostro autore italoamericano preferito oltre a voi stessi"? Ricordava spesso questo aneddoto: "Si poteva sentire cadere uno spillo".

Per lui, questo dimostrava che gli scrittori italoamericani non prestavano attenzione, non leggevano e non si ascoltavano. Così le tre regole iniziali di IAWA sono: 1) Leggersi a vicenda, 2) Scrivere o farsi scrivere, 3) Comprare i nostri libri, a cui ho aggiunto 4) Recensirsi a vicenda.

Molti autori italoamericani erano presenti, ma sono stati Viscusi e la recentemente scomparsa Vittoria Repetto ad impegnarsi per portare alla serie di letture nel 1991, rendendola il forum più democratico della nostra comunità in quanto presenta autori emergenti e veterani che leggono le loro opere ad alta voce davanti a un pubblico. Farlo è un atto molto significativo.

La serie è continuata all'ormai chiuso Cornelia Street Café con Vittoria Repetto fino a quando non sono iniziate le conferenze alla libreria Bluestocking's. Viscusi chiese a me e a Gil Fagiani di organizzare, insieme, forse 15 o 16 anni fa. Ad un certo punto, il nostro programma al Cornelia Street Café fu ridotto e organizzammo delle letture al Sidewalk Café, entrambe le sedi sono state poi vittime del mercato immobiliare di NYC, ferocemente competitivo e devastante.

Abbiamo spostato le letture alla filiale della New York Public Library a Mulberry Street nel cuore di Little Italy, un meraviglioso spazio gratuito.

Tre anni fa, una seconda serie è iniziata a Boston alla libreria I AM Bookstore curata da Julia Lisella e Jennifer Martelli. La libreria ha chiuso ma il suo business online è in crescita.

Dopo la pandemia, noi tre abbiamo co-curato virtualmente le letture mensili di IAWA. La serie compie quest'anno 30 anni, e potrebbe essere una delle serie letterarie più longeve di New York e Boston.

Siete tre poeti in famiglia: come funziona?

Sì, mia sorella Julia Lisella e il mio defunto marito Gil Fagiani sono poeti e l'aspetto piacevole di questo è che quando uno di noi raggiunge qualche successo o progresso editoriale, è come se tutti e tre avessimo ottenuto quel risultato.

Imparo da entrambi: tutti e tre osserviamo il mondo attraverso lenti molto diverse, e abbiamo avuto esperienze di vita ed educazione molto varie, così mentre le nostre voci si muovono attraverso un filtro etnico comune, sono molto distinte. Anche le nostre abitudini di lavoro sono molto varie, eppure siamo disponibili l'uno per l'altro.

Ho perso il mio primo redattore quando Gil è morto nel 2018. Eravamo i primi lettori di tutto ciò che entrambi scrivevamo e tenevamo una cartella chiamata Scambio in salotto dove ognuno di noi metteva un nuovo lavoro e l'altro lo leggeva a suo piacimento e lo rimetteva a posto con i suoi suggerimenti o modifiche. Era un grande sistema che mi manca molto. Da quando mio marito non c’è più, ho curato il suo settimo libro di poesia, Missing Madonnas, il terzo della sua trilogia del Connecticut e con l'assistenza del suo mentore e amico Luigi Bonaffini, la sua raccolta bilingue è in lavorazione. Ho un chapbook in attesa di pubblicazione e Gil e io stavamo lavorando a una raccolta insieme.

L'Italia ha dato i natali a molti poeti e poetesse nel corso dei secoli. Perché pensi che gli italiani siano così tanto attratti dalla poesia, dall'arte e dalla cultura nel corso dei secoli?

Penso che gli italiani e gli italoamericani siano persone espressive - i primi immigrati eccellevano nello sviluppo del teatro, quindi il teatro ci viene facile. Per estensione, penso che la nostra comunità abbia meno paura di esprimere emozioni e di affrontare eventi della vita reale, personale e politica.

Possiamo vedere dalla recente poesia che Amanda Gorman ha scritto e letto che la poesia non è un'arte passiva o necessariamente romantica, anche se può esserlo; è molto attiva e può interpretare l’attualità in un modo che può essere compreso.

Recentemente mi sono trovata a rispondere alla domanda "Chi o cosa ti ha ispirato a scrivere?" Sorprendentemente, ho menzionato la mia nonna calabrese, Filomena Calabro, per aver arricchito la mia vita con la sua lingua e credo che la poesia cominci proprio con l'amore per la lingua, il suono, i puzzle che si possono risolvere e i messaggi e le storie che si possono raccontare.

La poesia viene letta ai funerali, ai matrimoni, ai battesimi, ai momenti di significato pubblico ed emotivo. Può essere un'arte curativa in un certo senso, può anche smuovere l'anima, far rivivere vecchi ricordi: in breve, portarti dove non sei mai stato prima.

All'interno della nostra comunità alcuni spiccano in termini di influenza. Maria Mazziotti Gillan, che ha pubblicato più di 20 libri di poesia e ricevuto molti premi, ha avuto un'enorme influenza. Come fondatrice e direttrice esecutiva del Poetry Center al Passaic County Community College di Paterson, New Jersey e redattrice della Paterson Literary Review, Gillan è stata la voce giusta al momento giusto: il suo lavoro ha aperto le porte agli scrittori che hanno potuto emergere con la loro identità e la loro voce intatte. Molte altre voci nella nostra comunità, come Maria Fama, sono molto intimamente legate alla cultura regionale.

Non mi perdonerei se non menzionassi l'importanza crescente della traduzione. Luigi Bonaffini e Michael Palma ci hanno dato grandi traduzioni di Dante, Mario Luzzi e di molti altri poeti italiani ai quali non abbiamo accesso in lingua originale. Il defunto Alfredo di Palchi, che ha prodotto la rivista letteraria Chelsea, ha anche sostenuto per molti anni il Premio Bordighera che forniva ai vincitori una traduzione della loro opera dall'inglese all'italiano.

We the Italians facilita il fatto che l'Italia e gli italiani che vivono qui possano conoscere e apprezzare meglio la meravigliosa comunità italoamericana e i suoi fantastici membri. Cosa possiamo fare per aiutare a promuovere la poesia italiana negli Stati Uniti e la poesia italoamericana in Italia?

Su questa domanda assumerò un tono brusco. Gli italoamericani si lamentano a gran voce degli stereotipi nei media, ma non comprano i nostri libri né sostengono gli scrittori: i nostri libri sono pieni da cima a fondo di una pluralità di personaggi che non sono stereotipati. Uno dei nostri illustri studiosi ha suggerito a un'importante organizzazione italoamericana di comprare i nostri libri e spedirne uno ad ogni nuovo iscritto. L'organizzazione si è rifiutata di farlo sostenendo che loro appoggiano solo cause di carattere scientifico. Sviluppare una tradizione di filantropia culturale è in cima alla lista dei miei desideri per la comunità Italoamericana.

Al contrario, un esempio di come la comunità si sia unita per sostenere uno sforzo comune è stata la storica traduzione e pubblicazione di ItaloAmericana (Fordham University Press), antologia curata dal defunto Francesco Durante, Robert Viscusi e Anthony Tamburri e interamente finanziata dagli italoamericani.

Quasi interamente tradotta da italoamericani, questa raccolta porta un pubblico di lingua inglese e una nuova generazione faccia a faccia con questi lunghi scritti inaccessibili, dalla poesia al dramma al giornalismo, all’attivismo politico, alla storia, alle memorie, alla biografia e al racconto. Un must-have sul vostro scaffale.

E come scrittrice di viaggi, suggerisco di viaggiare verso le vostre radici - da dove i vostri parenti sono venuti veramente – e visitare non solo l'Italia altolocata di Roma, Firenze e Venezia, ma le piccole, raccolte e talvolta dimenticate o abbandonate città e villaggi - è una delle esperienze più arricchenti che ci si possa concedere.

Ho fatto delle presentazioni discutendo su quanto sia importante per gli italoamericani sapere chi sono veramente - il loro background ha molto meno a che fare con la Monna Lisa e i Medici che con la vita di paese, l'artigianato, i racconti popolari, la musica, i miti. Certo, la maggior parte ha perso la propria lingua madre, ma studiare l'italiano valorizza la cultura e mantiene vivi i nostri legami con ciò che siamo. Inoltre, gli italoamericani devono iscriversi ai corsi di italiano se si aspettano che le scuole li aggiungano ai programmi.

In un certo senso, coloro che perdono queste opportunità sono come orfani culturali - non sono né italiani né americani.

Tu sei anche una scrittrice di viaggi, e immagino che tu abbia viaggiato molto in Italia. Qual è il tuo posto preferito, e quale quello che non consiglieresti, in Italia? C'è una gemma nascosta che pochi italoamericani probabilmente conoscono e che ti piacerebbe condividere con i nostri lettori?

Questa è una domanda divertente perché se c'è un posto che ho amato così tanto, vorrei tenerlo per me. Questo è quello che ho provato per la Sicilia nel momento in cui l'ho visitata durante la mia luna di miele. Naturalmente, la Sicilia è un posto che prima o poi sarebbe stato scoperto. Anni fa, durante una conferenza sull'Italia meridionale presso un gruppo di agenti di viaggio, feci una presentazione sulla Sicilia. Mario Perillo era tra il pubblico in quel momento, saltò su e disse: "Andare in Sicilia è come portare la gente a visitare l'Alabama invece delle grandi attrazioni". Suo figlio Steve ride di questo perché non molto tempo dopo, Perillo Tours ha sviluppato programmi per la Sicilia e sono tra i loro best seller.

Citerei anche il magnifico e spietato paesaggio della Calabria e i piccoli paesi di montagna di Albidona o i borghi ben conservati come Morano Calabro, due luoghi che vale la pena visitare, uno con vista sul Mar Ionio. Ho avuto modo di conoscere recentemente questi luoghi quando ho seguito il corso sulla diaspora italiana sponsorizzato dall'Università della Calabria nel 2019.

Ogni regione d'Italia ha le sue gemme incredibili, è davvero una delle destinazioni più multiculturali del pianeta.

Il mio lavoro di scrittrice e redattrice di viaggi mi ha portato in 60 paesi negli ultimi 20 anni circa, offrendomi incredibili opportunità non solo di incontrare persone di diversi gruppi etnici, cosa che già faccio a casa mia nel mio quartiere, ma di incontrarli nei loro paesi di origine.

Gran parte delle mie poesie provengono dalle parole di guide, cuochi, camerieri o colleghi che ho incontrato in tutto il mondo. Cerco di dare voce alle loro storie nella mia poesia.

Ho fatto quest'ultima domanda a molti italoamericani, ma mai a una poetessa. Vorrei provare a mescolare sacro e profano, alto e basso, se posso... Non resisto, chiedo: sauce or gravy (salsa o sugo)?

I miei nonni la chiamavano la salsa ... la salsa per noi era marrone e probabilmente americana, ma le mie sorelle ricordano che mia madre iniziò a chiamarla gravy. E questo è piuttosto divertente perché mia nonna calabrese ha sempre accusato mia madre di cercare di essere più 'mericana come lo erano le sue amiche irlandesi. Questo portò ad una battaglia sulla mia frequentazione della scuola cattolica perché mia nonna insisteva che le suore, essendo per lo più irlandesi, non ci avrebbero capito. In un certo senso aveva ragione - la mia prima ribellione pubblica fu la correzione di una suora che cercò di anglicizzare il mio nome in Marie o Mary. Mio padre fu chiamato a scuola e miracolosamente difese la mia posizione: "Maria è un nome molto facile da pronunciare in inglese e dopo tutto è il nome della Beata Vergine". Quelle suore erano le donne più istruite che io abbia mai conosciuto, vivevano senza uomini in una società comunitaria e mi hanno insegnato a leggere e scrivere.

La mia merenda dopo la scuola non era costituita da biscotti e latte, ma da un croccante pezzo di pane italiano cosparso di olio d'oliva dorato, sale e origano. I bambini americani dicevano che sembravano "insetti sul pane", ma io ne sapevo di più di loro