If there is a story that all Italian Americans and all Italians living in Italy should know, it is the story of Amadeo P. Giannini: he realized the American dream, not only for himself, but for an entire society. There are so many reasons why, today more than ever, the story of his life tells the best part of the Italian DNA, whether you live in Italy or in the United States.

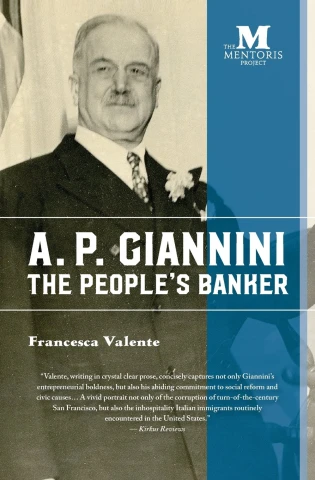

To tell it all is not an easy task: Prof. Francesca Valente did it very well in her book "A.P. Giannini: The People's Banker", published for the series called "The Mentoris Project". Prof. Valente has been Director of several Italian Cultural Institutes in North America, and coordinator of the entire area when she was directing the one in Los Angeles. We welcome and thank her very much for helping us to tell our readers about the life of this extraordinary Italian who died exactly 70 years ago, on June 3, 1949.

Prof. Valente, in the story of Amadeo Peter Giannini we find his parents who left Italy, their son born in America, hard work, innovation and ingenuity, solidarity with other Italian Americans and with Italy, success. We are talking about a universal pioneer, but can we say that this is also a typical story of Italian emigration to the USA?

I'd say not. It's not exactly a typical story, but rather an exception. The stereotype of the Italian immigrant was Al Capone, Frank Sinatra, or the penniless immigrant, always seen in a mostly negative light. The Italian immigrant aspired to a better life, but success was not a foregone conclusion. Giannini's uniqueness was to be able to understand that Italian immigrants were discriminated against and despised; he therefore stood by them to grow both the Italian American community and all of California, which was in a period of great expansion.

There was an interesting confluence of different elements that characterized the success of Giannini, precisely because he was the son of humble origins of this first wave of immigration. His father Luigi went from the gold rush to the creation of a farm, together with Virginia, his wife. A life full of promise was abruptly interrupted when Amadeo, at the age of 7, saw his father die before his eyes for an absurd dispute: he had paid a farmhand a dollar less than agreed. I think this was when Amedeo Giannini became an adult, even if he was only 7 years old.

He somehow, very generously, wanted to help his mother; after four years of mourning she remarried Lorenzo Scatena, who became the

stepfather of her three children. An extraordinary, affectionate alliance was born, full of esteem and willingness to help each other, between Amadeo and Lorenzo, whom the child called Pop. Then, when he was fifteen, Amadeo realized that he had learned everything school could ever teach him. But this did not mean banning culture and education from his life; on the contrary, he always supported his brother Attilio until he got his medical degree at Berkeley.

Amadeo felt, however, that he had to be more and more effective, that he had to improve the standard of living of the family. This led him to go out to the port at night with his stepfather and fit into that multi-ethnic microcosm, which was his actual great school. That is where he understood whom he had to deal with, a very humble low-middle class: the future customers of his bank. He then began to copy all the lists of agricultural products that the ships carried in beautiful handwriting and to actively help the family. He left school and dedicated himself to his stepfather's company, at which he became a partner and sales manager at the age of nineteen.

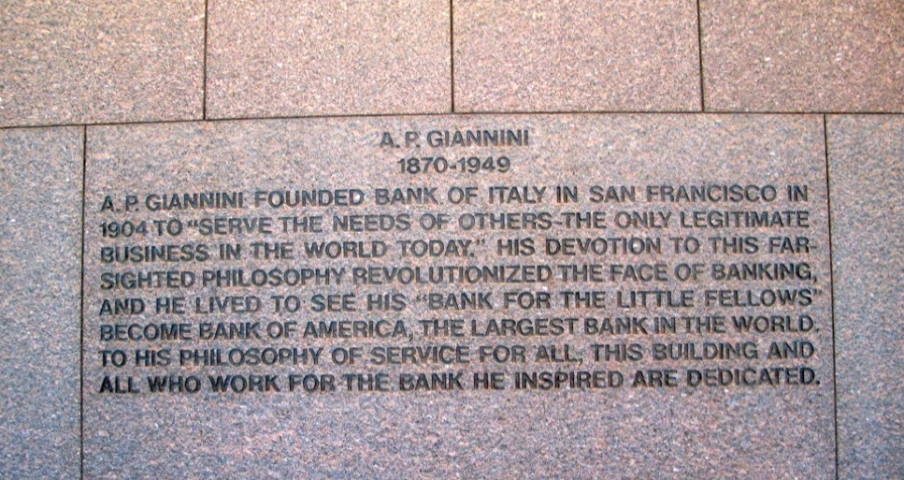

In 1904 Giannini founded the Bank of Italy. He was one of the first bankers to lend money to middle-class and immigrants, to the entrepreneurs of tomorrow, looking in their eyes for the drive that would ensure that they would do anything to succeed and repay the loan they asked for, without the possibility of guaranteeing collateral and sometimes based on a simple handshake...

His bank was a completely different bank from any other, based on absolute generosity, but above all on a new vision developed by staying in touch with ordinary people. When his father-in-law died, he did not inherit anything: he was simply the executor of the assets helping in investing money for his widow and many children. One of these assets was a stake in the capital of a small bank, the Columbus Savings and Loans. It was a very conservative credit institution, inclined to grant loans only to wealthy customers.

Giannini's intuition, which came from a completely different world, extraneous to high finance, was to radically change the bank's approach. Not being able to convince the members of the Board to a new, more democratic orientation, granting loans also to the less well-off immigrants, without subjecting them to usury, at 34 years of age he managed to found his own bank, the Bank of Italy.

It was not only a question of helping the poorest immigrants to overcome their distrust of the banks, but also of making them grow by encouraging them to become account holders first and then shareholders.

The family-run bank, with a board of Italian businessmen, was also open on Saturdays and Sundays, and in the evenings: Giannini had always had a deep educational spirit towards users. He wanted his account holders to be well informed about what the bank could do for them, just as he had informed farmers at the market back in the day.

After the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco, Giannini was one of the very few bankers who immediately provided funds to rebuild the city, on its knees after being almost destroyed...

Unlike other bankers, Giannini had not intimidated the man in the street: on the contrary, he had created the first bank in a saloon, an open space without private offices. In the same way, after the earthquake he understood before and better than anyone else what was happening. He had the great intuition to bring all the cash of the Bank of Italy to Seven Oaks, his residence in San Mateo. When he returned to San Francisco, the bank was destroyed; if he had not made such a bold decision, all the assets would have been lost. Unlike the other banks that had decided to delay the technical time to access the remaining liquidity after such a tragedy, Giannini had the readiness of spirit to understand that that was the time to start helping the survivors of the earthquake. According to him, it was not necessary - as the other banks claimed - to wait six months before making decisions and then acting.

From an improvised counter at the pier, he began to distribute cash to those in need, giving half of what people were asking for. Why was that? Always for educational reasons: half and not all, because the man in the street had to secure the other half for himself, because he had to build his own destiny, his own future. This was the philosophy of Giannini, who managed to achieve a social utopia by giving confidence to others, using money not for personal purposes, but to improve the living conditions of others.

Giannini's remarkability was to realize the American dream and to share it with millions and millions of Californians, not only Italian Americans. It was the earthquake that made him a national hero, because without profiting he helped everyone to rebuild San Francisco and not to abandon the city. In fact, a year after the earthquake, North Beach - the Italian heart of San Francisco - was the first neighborhood in the city to rise again as timber prices skyrocketed.

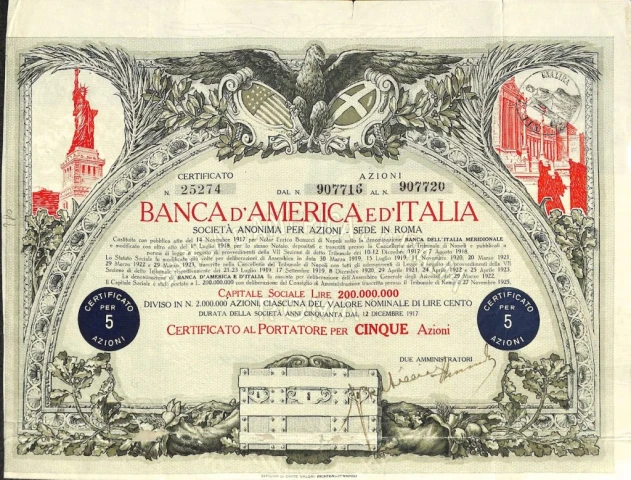

In 1919, Giannini's Bank of Italy bought Banca dell'Italia Meridionale, which was renamed Banca d'America e d'Italia in 1922. In 1932 it supported 15% of Italian exports to the United States and after the Second World War it became the bank of reference for the reconstruction of the country, managing 20% of the proceeds of the Marshall Plan, introducing consumer credit in Italy and helping the country recover after the war

Giannini was deeply proud of his Italian origins and was therefore very happy to acquire a bank in Italy, in Naples to be exact, where he then sent his son Mario who began a brilliant career, becoming an assistant to the President.

Giannini had also realized the inconsistency of the American banking system, so it was easier to open a branch abroad than at home. From that moment on, he dedicated the rest of his life to branch banking and went to Canada where this system had been very successful, unlike the United States. In fact, it was the forerunner of what today is the ATM, that is the possibility of having various points where the worker, farmer or entrepreneur could go to withdraw his money in case of need. This is why the Bank of Italy, driven by a true spirit of service, was also open on Saturdays, Sundays and in the evening hours.

The Banca d'America e d'Italia opened 31 branches and came to have assets of 30 million dollars. It survived Fascism and the war, and became the bank of reference for the reconstruction of Italy. Giannini managed to include it in the aid program of the Marshall Plan: he wanted to revive Italy and in particular the industries that had been destroyed during the Second World War. He supported Fiat, Alfa Romeo and many other industries. RAI and some universities also benefited from this contribution.

In 1929 the Bank of Italy merged with the Bank of America, and Giannini led the new bank until 1945...

The process was a bit more complex than that. In those years, Giannini had tried at least three times to retire, because he was a very generous spirit and wanted to leave room for young people: but he had never succeeded. Since the founding of the Bank of Italy, his dream had been to make it to New York, thus building a bridge between the American West and East. He arrived in New York where the financial group of JP Morgan, an extremely snobbish and conservative New York group, did not appreciate the emergence of a newly rich former farmer and looked at him with great contempt.

Giannini continued his plan by creating the Bank of America, but at a certain point he made a mistake. Feeling confident in choosing Elisha Walker as his successor, he retired. He soon understood he made the wrong choice: Elisha Walker, a Yale graduate, was part of that elite group close to JP Morgan and within a few years he cleverly tried to dismantle the entire structure of the Bank of America and its subsidiaries.

Despite his poor state of health, Giannini had to get back in, appeal to the shareholders and, with a masterful coup, regain the command of the Bank of America. He headed it until the year of his death in 1949 at the age of 79. He realized that he should have preferred his son Mario to the Yale's graduate.

For years and years Giannini had received a symbolic salary of one dollar a year, plus a reimbursement of expenses. He didn't want to become rich because he was convinced that wealth would end up owning him, and not the other way around. He had great respect for money, but only if used well and for social purposes to improve his life and that of others. When the bank assigned him a million and a half dollars, which was 5% of that year's earnings, Giannini did not cash the check but donated it to the University of Berkeley for the foundation of a chair of agriculture. Giannini was never embarrassed to recognize his origins: indeed, he was proud to be the son of farmers of humble origins and wanted this discipline to have a scientific and academic depth. The same thing happened with the establishment of a chair, still existing, of Italian language and culture at the University of Berkeley.

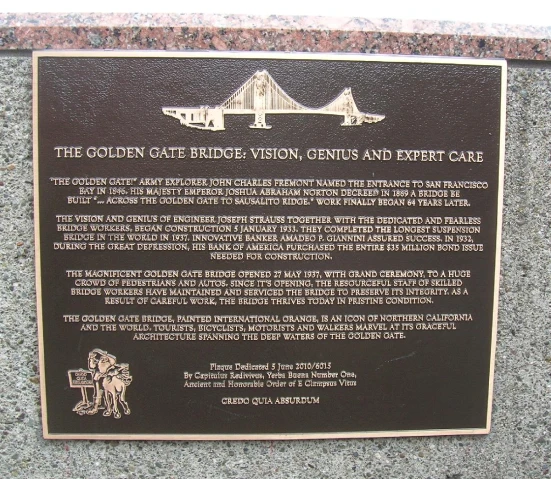

Giannini was also an exceptional forerunner of modern Venture Capital: he helped Hewlett and Packard to give life to their company and in fact to the whole Silicon Valley, he was among those who allowed the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge, and the only one who believed in the visionary who wanted to make a feature cartoon movie, Walt Disney

He knew the potential of every historical moment. In the war period, for example, he helped large companies to transform by adapting to the needs of the time, and then helped them to reconvert again once the war was over.

As far as the film industry is concerned, he saw not only its interest as a source of investment, but also its cultural value. The film industry in which Giannini began to invest was mainly promoted by Jewish immigrants, who were marginalized and discriminated against, like the Italians. He understood the social value of this new art that, unlike opera, could guarantee everyone, a new form of entertainment for a few dollars, allowing them to daydream about a better future.

In the same way, the investment in the Golden Gate Bridge created a social utopia. By financing Joseph Strauss, the German-born engineer that no one had taken seriously, Giannini created thousands of jobs in the midst of the Depression. The Golden Gate's gamble at the area's most treacherous location meant not only a link between Southern California and Northern California but also opened access to the entire northern United States.

It was an incredible challenge. In the midst of an economic crisis, at a point where the currents were very strong, at a time when the federal authorities had already invested in another bridge, the Bay Bridge.

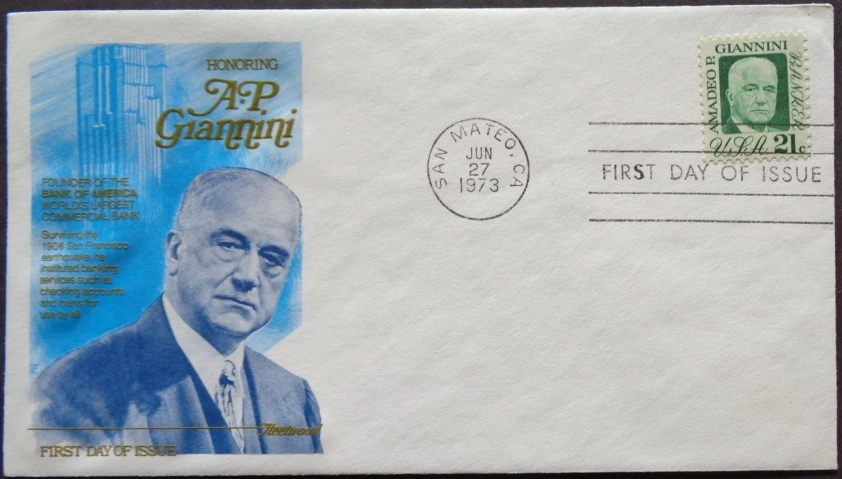

In 1973 the American postal service issued a commemorative stamp, while Time Magazine described Giannini as one of the "builders and titans" of the 20th century. He was the only banker included in Time 100, a list of the most important characters of that century.

Certainly he was acknowledged because when Amadeo Giannini died in 1949, Bank of America was the world's largest private bank with 517 branches. His dream had come true after so much suffering, so many enemies, so many battles won in a very bold way and with branches not only in California, but in all the United States and in China, Japan, the Philippines and the Far East.

I would also like to point out that, although he founded what became the largest private bank in the world, Giannini's personal capital, when he died, was lower than that it was before founding the Bank of Italy. His goal was not to get rich, but to improve the quality of life in California. This is his originality, because he succeeded in transforming the working class into the middle class, making a social and economic leap for Californians and the Italian immigrants, who were previously ignored and marginalized. Giannini gave them dignity, helped them to become American citizens, aware of their European roots.

In addition, he fought all his life for the values he believed in. He was against money as an end in itself: madness for a banker. There was a deep respect for money in him, but only if used to improve the lives of others. In fact Giannini never financed any speculator, but only those who wanted to buy a house, a car: to do so he invented the credit card. He was able to build a social utopia.

The funeral of Giannini was attended by many representatives of the world of finance, but also farmers, entrepreneurs, merchants, ordinary people who had their lives changed by his vision: it is no coincidence that his book is called "A.P. Giannini: The People's Banker". Is it true that the character of George Bailey in Frank Capra's It’s a Wonderful Life is inspired by Giannini, who was very close to Capra?

I'm not sure: maybe yes, in some ways, because in the movie Bailey was extremely altruistic and always wanted to help others. In this I feel the protagonist of It’s a Wonderful Life by Frank Capra can certainly be inspired by Giannini for his extraordinary generosity. But Giannini had also distinguished himself for his resilience, for his spiritual strength in facing every adversity. He had eight children and six died of hemophilia. Any other human being would have withdrawn, closed himself up in his bank and received no one; instead, he continued to help others realize their dreams.

Giannini was a very spiritual man: he was deeply religious and Catholic, but not bigoted, he also helped many churches of other denominations. He had within himself the spiritual strength of those who had overcome adversity, always thinking of that episode as a child that had marked him forever: the death of his father for not giving an extra dollar to a worker, as he had asked him. I think that, in tragedy, this cathartic event changed his life, prompting him to give money its rightful value.

Se c’è una storia che tutti gli italoamericani e tutti gli italiani che vivono in Italia dovrebbero conoscere, è quella di Amadeo P. Giannini: che realizzò il sogno americano, non solo per lui, ma per un’intera società. Sono davvero tanti i motivi per cui, oggi più che mai, le sue vicende raccontano la parte migliore del dna italiano, sia che si viva in Italia, sia che si viva negli Stati Uniti.

Raccontarle tutte e bene non è impresa facile: ci è riuscita molto bene la Prof.ssa Francesca Valente nel suo libro “A.P. Giannini: The People's Banker”, uscito per la collana chiamata “The Mentoris Project”. La Prof.ssa Valente è stata direttrice di diversi Istituti di Cultura italiani in Nord America, e coordinatrice dell’intera area quando dirigeva quello di Los Angeles. Le diamo il benvenuto ringraziandola davvero per aiutarci a raccontare ai nostri lettori la vita di questo straordinario italiano che morì esattamente 70 anni fa, il 3 Giugno 1949.

Prof.ssa Valente, nella storia di Amadeo Peter Giannini ci sono i genitori partiti dall’Italia, il figlio nato in America, il duro lavoro, l’innovazione e l’ingegno, la solidarietà con gli altri italoamericani e con l’Italia, il successo. Stiamo parlando di un pioniere universale, ma possiamo dire che questa è anche una tipica storia di emigrazione italiana negli USA?

Direi di no. Non è proprio una storia tipica, piuttosto un’eccezione. Lo stereotipo dell’immigrato italiano è stato Al Capone, Frank Sinatra, o l’immigrato squattrinato, visto sempre sotto una luce per lo più negativa. L’immigrato italiano aspirava ad una vita migliore, ma il successo non era scontato. L’unicità di Giannini fu di riuscire a capire che gli immigrati italiani erano discriminati e disprezzati; si mise quindi al loro fianco per far crescere sia la comunità italoamericana sia tutta la California che si trovava in un momento di grande espansione.

C’è stato un interessante confluire di elementi diversi che ha caratterizzato il successo di Giannini, proprio perché era figlio di umilissimi origini di questa prima ondata di immigrazione. Suo padre Luigi passò dalla corsa all’oro alla creazione, con Virginia, sua moglie, di un’azienda agricola. Una vita ricca di promesse interrotta bruscamente quando Amadeo, a 7 anni, vide morire il padre davanti ai suoi occhi per una disputa assurda: aveva pagato un bracciante un dollaro in meno di quanto pattuito. Penso sia stato questo il primo momento di presa di conoscenza di Amedeo Giannini, ovvero il momento in cui divenne adulto, anche se aveva solo 7 anni.

Volle in qualche modo, molto generosamente, aiutare sua madre; dopo quattro anni di lutto lei si risposò con Lorenzo Scatena, che divenne il patrigno dei suoi tre figli. Nacque una straordinaria, affettuosa alleanza, piena di stima e di volontà di aiutarsi l’un l’altro tra Amadeo e Lorenzo, che il bambino chiamava Pop. Poi, Amadeo a quindici anni si rese conto di avere avuto dalla scuola tutto il possibile. Ma questo non significò bandire la cultura e l’istruzione dalla propria vita, anzi sostenne sempre il fratello Attilio finché ottenesse la laurea in medicina a Berkeley.

Amadeo sentiva però di dover essere sempre più operativo, di dover migliorare il tenore di vita della famiglia. Questo lo portò ad uscire di notte per andare al porto col patrigno e inserirsi in quel microcosmo multietnico, che fu la sua vera grande scuola. E’ lì che capì con chi doveva avere a che fare, cioè con un ceto medio-basso, molto umile: i futuri clienti della sua banca. Cominciò quindi a ricopiare in bella grafia tutti gli elenchi dei prodotti agricoli che portavano le navi e ad aiutare attivamente la famiglia. Lasciò la scuola e si dedicò all’azienda del patrigno della quale a diciannove anni divenne partner e direttore delle vendite.

Nel 1904 Giannini fondò la Bank of Italy. Fu tra i primi banchieri a prestare soldi alla middle-class e agli immigrati, agli imprenditori del domani, cercando nei loro occhi il drive che assicurasse che avrebbero fatto di tutto per avere successo e restituire il prestito che chiedevano, senza possibilità di garantire collaterali e a volte basandosi su una semplice stretta di mano…

La sua banca era una banca completamente diversa da ogni altra, fondata sulla generosità assoluta, ma soprattutto su una nuova visione elaborata restando in contatto con la gente comune. Alla morte del suocero ereditò l’impero immobiliare della famiglia e si ritrovò proprietario anche di una partecipazione al capitale di una piccola banca, la Columbus Savings and Loans. Si trattava di un istituto di credito molto conservatore, incline a concedere mutui solo a clienti benestanti.

L’intuizione di Giannini, che proveniva da un mondo completamente diverso, estraneo all’alta finanza, fu di cambiare radicalmente l’impostazione della banca. Non riuscendo a convincere i componenti del Board ad un nuovo orientamento più democratico, concedendo prestiti anche agli immigrati meno abbienti, senza costringerli all’usura, a 34 anni riuscì a fondare una propria banca, la Bank of Italy.

Si trattava non solo di aiutare gli immigrati più poveri a superare la diffidenza nei confronti delle banche ma anche di farli crescere incoraggiandoli a diventare prima correntisti e poi azionisti.

La banca a gestione familiare, con un Board di uomini d’affari italiani, era aperta anche di sabato e di domenica, e la sera: Giannini aveva da sempre un profondo spirito educativo nei confronti degli utenti. Voleva che i suoi correntisti fossero bene informati su quello che la banca poteva fare per loro, così come a suo tempo aveva informato gli agricoltori al mercato.

Dopo il terremoto del 1906 a San Francisco, Giannini fu tra i pochissimi banchieri che immediatamente misero a disposizione fondi per ricostruire la città, in ginocchio dopo essere stata quasi distrutta…

A differenza degli altri banchieri, Giannini non aveva intimidito l’uomo della strada: al contrario, aveva realizzato la prima banca in un saloon, uno spazio aperto senza uffici privati. Allo stesso modo, dopo il terremoto capì prima e più di chiunque altro cosa stava succedendo. Ebbe la grande intuizione di portare tutti i contanti della Bank of Italy a Seven Oaks, nella sua residenza di San Mateo. Quando tornò a San Francisco la banca era distrutta; se non avesse preso una decisione cosi ardita tutto il patrimonio sarebbe andato perduto. A differenza delle altre banche che avevano deciso di procrastinare i tempi tecnici per accedere alla liquidità residua dopo una tragedia del genere, Giannini ebbe la prontezza di spirito di capire che era quello il momento in cui iniziare ad aiutare i sopravvissuti del terremoto. Secondo lui non si doveva - come sostenevano le altre banche - aspettare sei mesi prima di prendere delle decisioni e poi agire.

Da un bancone improvvisato al molo, iniziò a distribuire denaro contante a chi ne aveva bisogno, concedendo la metà di quanto le persone chiedevano. E questo perché? Sempre per motivi educativi: metà e non tutto, perché l’altra metà, l’uomo della strada doveva procurarsela da sé, perché doveva costruirsi il proprio destino, il proprio futuro. Questa era la filosofia di Giannini, che riuscì a realizzare un’utopia sociale dando fiducia al prossimo, usando il denaro non per fini personali, ma per migliorare le condizioni di vita degli altri.

L’eccezionalità di Giannini fu quella di realizzare il sogno americano e di condividerlo con milioni e milioni di californiani, non solo italoamericani. Fu proprio il terremoto a renderlo un eroe nazionale, perché senza lucrare aiutò tutti a ricostruire San Francisco e a non abbandonare la città. Ma non fu solo questo: incoraggiò l’acquisto immediato del legname necessario alla ricostruzione; infatti, un anno dopo il terremoto, North Beach - il cuore italiano di San Francisco - fu il primo quartiere della città a risorgere mentre i prezzi del legname salivano alle stelle.

Nel 1919 la Bank of Italy di Giannini acquistò la Banca dell’Italia Meridionale, poi ribattezzata nel 1922 Banca d’America e d’Italia. Nel 1932 sosteneva il 15% delle esportazioni italiane verso gli Stati Uniti e nel secondo dopoguerra divenne la banca di riferimento per la ricostruzione del Paese, gestendo il 20% dei proventi del Piano Marshall, introducendo il credito al consumo anche in Italia e aiutando il Paese a riprendersi nel dopoguerra.

Giannini era profondamente fiero delle sue origini italiane e quindi ben lieto di acquistare una banca in Italia, precisamente a Napoli, dove poi inviò il figlio Mario che iniziò una brillante carriera, divenendo assistente del Presidente. Giannini si era anche reso conto dell’incongruenza del sistema bancario americano, per cui era più facile aprire una filiale all’estero che non in patria. Da quel momento dedicò il resto della sua vita al branch banking e andò in Canada dove questo sistema aveva registrato grande successo, a differenza degli Stati Uniti. Di fatto era l’antesignano di quello che oggi è il bancomat, cioè la possibilità di avere vari punti in cui il lavoratore, l’agricoltore o l’imprenditore poteva andare a prelevare il suo denaro in caso di necessità. E’ questo il motivo per cui la Bank of Italy, animata da vero spirito di servizio, restava aperta anche di sabato, domenica e nelle ore serali.

La Banca d’America e d’Italia aprì 31 filiali e arrivò ad avere un patrimonio di 30 milioni di dollari. Sopravvisse al fascismo e alla guerra, e divenne la banca di riferimento per la ricostruzione dell’Italia. Giannini riuscì ad inserirla nel programma di aiuti del Piano Marshall: voleva risollevare l’Italia e in particolare le industrie che erano andate distrutte durante la Seconda guerra mondiale. Sostenne la Fiat, l’Alfa Romeo e numerose altre industrie. Anche la Rai e alcune università beneficiarono di questo contributo.

Nel 1929 la Bank of Italy si fuse con la Bank of America, e la nuova banca fu guidata da Giannini fino al 1945…

Il processo fu un po’ più complesso. In quegli anni, Giannini aveva provato almeno tre volte ad andare in pensione, perché era uno spirito molto generoso e voleva lasciare spazio ai giovani: ma non c’era mai riuscito. Sin dalla fondazione della Bank of Italy il suo sogno era stato di arrivare a New York costruendo così un ponte tra l’Ovest e l’Est americano. Arrivò a New York dove il gruppo finanziario di JP Morgan, gruppo newyorchese estremamente snob e conservatore non apprezzava l’affermarsi di un ex-contadino arricchito e lo guardava con grande disprezzo.

Giannini portò avanti questo suo progetto creando la Bank of America ma ad un certo punto commise un passo falso. Sentendosi sicuro nella scelta di Elisha Walker come suo successore, andò in pensione. Ben presto dovette constatare di aver fatto la scelta sbagliata: Elisha Walker, laureato a Yale, faceva parte di quel gruppo elitario vicino a JP Morgan e nel giro di pochi anni cercò astutamente di smantellare tutto l’assetto della Bank of America e le sue filiali.

Nonostante il suo cattivo stato di salute, Giannini dovette tornare in campo, appellarsi agli azionisti e riprendere con un colpo di mano magistrale il comando della Bank of America. Ne fu a capo fino all’anno della sua morte nel 1949 a 79 anni. Si era reso conto che al laureato di Yale avrebbe dovuto preferire suo figlio Mario.

Giannini per anni e anni aveva percepito uno stipendio simbolico di un dollaro l’anno, più un rimborso spese. Non voleva diventare ricco perché era convinto che la ricchezza avrebbe finito per possederlo, e non il contrario. Aveva un grande rispetto per il denaro, ma solo se usato bene e a scopi sociali per migliorare la sua vita e quella degli altri. Quando la banca gli assegnò un milione e mezzo di dollari, cioè il 5% dei guadagni di quell’anno, Giannini non incassò l’assegno ma lo donò all’università di Berkeley per la fondazione di una cattedra di agricoltura. Giannini non fu mai in imbarazzo nel riconoscere le sue origini: anzi, era fiero di essere figlio di agricoltori di umili origini e voleva che questa disciplina avesse anche uno spessore scientifico e accademico. La stessa cosa avvenne con l’istituzione di una cattedra, tuttora esistente, di Lingua e cultura italiana presso l’Università di Berkeley.

Giannini fu anche un eccezionale precursore dei moderni Venture Capital: aiutò Hewlett and Packard a dare vita alla loro azienda e di fatto a tutta la Silicon Valley, fu tra coloro che permisero la costruzione del Golden Gate, e l’unico a credere a quel visionario che voleva fare un lungometraggio a cartoni animati, Walt Disney.

Seppe intuire il potenziale di ogni momento storico. Nel periodo bellico, per esempio, aiutò grandi imprese a trasformarsi adattandosi ai bisogni dell’epoca, per poi aiutarle di nuovo a riconvertirsi una volta finita la guerra.

Per quanto riguarda l’industria cinematografica, ne colse non solo l’interesse come fonte di investimento, ma anche il valore culturale. L’industria cinematografica in cui Giannini iniziò a investire era promossa principalmente da immigrati ebrei, che erano emarginati e discriminati come gli italiani. Capì il valore sociale di questa nuova arte che, a differenza del teatro d’opera, poteva garantire a tutti, per pochi dollari, una nuova forma di entertainment facendo sognar loro ad occhi aperti un futuro migliore.

Allo stesso modo l’investimento per il Golden Gate realizzò un’utopia sociale. Finanziando Joseph Strauss, l’ingegnere di origini tedesca che nessuno aveva preso sul serio, nel pieno della Depressione Giannini creò migliaia di posti di lavoro. La scommessa del Golden Gate nel luogo più infido della zona, significava non solo un collegamento tra la California del Sud e la California del Nord ma apriva l’accesso a tutto il Nord degli Stati Uniti.

Fu una sfida incredibile. In piena crisi economica, in un punto dove le correnti erano fortissime, in un momento in cui le autorità federali avevano già investito in un altro ponte, il Bay Bridge.

Nel 1973 il servizio postale Americano ha emesso un francobollo commemorativo, mentre Time Magazine ha descritto Giannini come uno dei “builders and titans” del XX secolo. Fu l'unico banchiere inserito nel Time 100, una lista dei personaggi più importanti di quel secolo.

Senz’altro lo riconobbero perché quando Amadeo Giannini è morto nel 1949, la Bank of America era la banca privata più grande del mondo con 517 filiali. Si era realizzato il suo sogno dopo tante sofferenze, tanti nemici, tante battaglie vinte in modo veramente audace e con filiali non solo in California, ma in tutti gli Stati Uniti e in Cina, Giappone, nelle Filippine e in Estremo Oriente.

Vorrei anche ricordare che, pur avendo fondato quella che divenne la banca privata più grande del mondo, il capitale personale di Giannini, quando morì, era inferiore a quello con cui era partito prima di fondare la Bank of Italy. Il suo obiettivo non era quello di arricchirsi, ma di migliorare la qualità di vita della California. È questa la sua originalità, perché riuscì a trasformare la classe operaia in classe media, facendo fare un salto sociale ed economico ai californiani e agli immigrati italiani, che prima erano ignorati ed emarginati. Giannini diede loro una dignità, li aiutò a diventare cittadini americani, consapevoli delle loro radici europee.

Inoltre, si batté per tutta la vita per i valori in cui credeva. Era contro il denaro fine a sé stesso: una follia per un banchiere. C’era in lui un profondo rispetto per il denaro, ma solo se usato per migliorare la vita degli altri. Difatti Giannini non finanziò mai alcun speculatore, ma solo chi voleva comprare una casa, un’automobile: per farlo inventò la carta di credito. È riuscito così a costruire un’utopia sociale.

Al funerale di Giannini parteciparono molti esponenti del mondo della finanza, ma anche contadini, imprenditori, mercanti, gente comune che ebbe la vita cambiata dalla sua visione: non a caso il suo libro si chiama “A.P. Giannini: The People's Banker”. E’ vero che il personaggio di George Bailey de ‘La vita è meravigliosa‘ di Frank Capra è ispirato a Giannini, che di Capra era molto amico?

Non ne sono sicura: forse sì, sotto certi aspetti, nel senso che nel film Bailey era estremamente altruista e voleva sempre aiutare gli altri. In questo sento il protagonista de “La vita è meravigliosa” di Frank Capra può essere senz’altro ispirato a Giannini per la sua straordinaria generosità. Però Giannini si era distinto anche per la sua resilienza, per la sua forza spirituale nell’affrontare ogni avversità. Ebbe otto figli e gliene morirono sei di emofilia. Qualunque altro essere umano si sarebbe ripiegato su se stesso, si sarebbe chiuso nella sua banca e non avrebbe ricevuto nessuno: invece continuò ad aiutare gli altri a realizzare i loro sogni.

Giannini era un uomo molto spirituale: era profondamente religioso e cattolico, ma non bigotto, aiutava anche molte chiese di altro culto. Aveva dentro di sé la forza spirituale di chi aveva superato le avversità, sempre pensando a quell’episodio che da bambino lo aveva segnato per sempre: la morte del padre per non aver dato un dollaro in più a un bracciante, come questi gli aveva chiesto. Io penso che, nella tragedia, questo fatto catartico cambiò la sua vita, spingendolo a dare al denaro il suo giusto valore.