This new interview is particularly dear to me for three reasons. The first is that it tells how even young Italians can be guided to learn about the sacrifice that thousands of American heroes made to liberate Italy. The second is that very often I get suggested interviews that are not exactly in the flow of this column, which explores new and special things and people and stories: so for today's guests I have to thank our mutual friend Elizabeth Bettina, who introduced us.

The third reason is that almost always my interviews are devoted entirely to something from the past, stories from the past; or entirely to stories from the present and the future. It is difficult for them to have past and future together. But this time that is exactly what happens. So I very gladly welcome on We the Italians Michael Wright and Alana Sacriponte, who run the Duquesne University Study Abroad program here in Rome

I would start by asking you to tell our readers about Duquesne University's study abroad program here in Rome. Who are your students, where are they from, what are they studying in Italy?

(Michael Wright) Duquesne University is a private, Catholic university in the Spiritan tradition located in Pittsburgh, PA with an international campus in Rome, Italy. 2021 marked the 20th anniversary of Duquesne’s campus in Rome, where we host 200 students annually on our beautiful property located with the Sisters of the Holy Family of Nazareth in the verdant Acquafredda Nature Reserve of Rome, near the busy working-class neighborhood of Boccea.

The Rome campus hosts students for a semester or a summer program from the university’s nine schools. The academic semesters are full of undergraduate students who work on their core curriculum classes in areas like art history, classical history, theology, sociology, intercultural studies, Italian language, along with specialty courses in education, business and the sciences. For Duquesne students, many of these subjects literally come alive by studying art and archaeology in the places where it happened.

Our summer programs are full of both undergraduate and graduate students studying music, nursing, and physical therapy providing historical context and health care comparisons that we hope will make Duquesne students competitive in their future academic and professional careers.

Do you have Italian American students? A few months ago I started to develop a theory, that is that Italian American kids are different from American kids of other ethnicity, and obviously different from Italian kids. What do you guys think about that?

(Alana Sacriponte) There are over 1.4 million Italian American people in the State of Pennsylvania and more than 15% of people identify as Italian American in Western Pennsylvania where our home campus is located. But if you have ever actually visited Pittsburgh, you would think the number was even higher than that! Pittsburgh’s Heinz History Center has one of the largest collections and archives of Italian American material culture. We also have a Little Italy neighborhood called Bloomfield, as well as many other “unofficial” Italian areas, like the Strip District, where Italian pride reigns. There are so many Italian Festivals throughout Pittsburgh and the suburbs, like an Italian Kennywood Day (our local theme park), and a local food and coffee scene that highlights Italian food and the Italian experience.

I would say that over half of the Duquesne University students who come to study at our Rome campus are Italian-Americans, and this experience is very different for them compared to their other classmates. The overall experience is the same, in that they engage with Italy’s incredible cultural patrimony like the art, food, language and music. But Italian American students who are also coming as heritage seekers are having a reckoning experience with their past, and one that can bring such strong emotions about returning to their family’s place of origin. This is probably one of the highlights of my job, helping Italian American students plan their travels to the small, remote villages of their great-grandparents, or ask for my help in translating a first-ever meet-up with Italian relatives during their semester abroad. Distant relatives who they have never met, most often with a big language barrier, cannot get in the way of this almost-sacred pilgrimage for these students. Students will visit incredible places like Venice, Florence and the Amalfi Coast, but nothing will ever compare to the experience of seeing the church where their great-grandfather was baptized, or meeting a cousin or great-uncle that they have heard about in stories from their families since they were born.

I know that I personally become super invested in helping these students, not only as a part of my job, but because that story is also my story. When I studied abroad in 2003 in this same program as an undergraduate student at Duquesne, I met my grandfather’s first cousin. It was the most moving experience for me to feel connected to his past, learn more about my family and feel an authentic connection to this country that has been such a big part of my life and traditions.

About our Italian American students, I think the most memorable story was an ex-student who had family in Abruzzo, in a small town near Pescara. He had never met them before, but they were so excited that he would be in Rome for three months that upon his arrival, his great aunt took a three-hour bus from Pescara to Rome, then our metro (or subway), and local bus to come meet him at campus. In her long journey, she brought along two teglie di parmigiana, or casserole dishes of eggplant parmesan, euro cash in case he didn’t have any, and continued to do this once a month while he was here. His aunt told me she felt it was her duty to make sure he was well-fed and to check in on him – almost like she had taken custody of him while on Italian soil. It was a beautiful thing to witness.

I really like the relationship you have established with a Roman high school near your campus. Based on your experience, what do Italian kids learn from this exchange, and what do American kids learn?

(Michael Wright) Duquesne in Rome’s relationship with the I.I.S. Einstein-Bachelet high school began in 2005, when we moved campus locations in 2004 to our current location in the Boccea neighborhood of Rome. The Einstein-Bachelet high school is located a half-mile (less than a kilometer) down the road from our campus. I continued to see other U.S. university programs in Rome and Florence offer reciprocity to their communities through musical performances, art installations at local schools and hospitals, and fashion shows of student creations.

I had been thinking about how to engage our students more fully with our local neighborhood, as well as giving something back to the city that graciously hosts us as U.S. Americans. One day when passing in front of the high school, I thought, “I wonder if we could create an exchange with students learning English at the high school to help them better their linguistic skills and in turn, they could help our students who were learning Italian?” After all, Italian students are 19 or 20 in their last year of high school and our students are mostly 19 and 20 years old as sophomores in college.

An enthusiastic meeting with the English language department resulted in an official gemellaggio, or sister-school agreement, that has been in effect ever since. Over the last 18 years, Duquesne’s relationship with the Einstein-Bachelet high school has resulted in nearly 1,000 Duquesne students working with nearly 1,000 of their Roman peers on projects, which has created many lasting friendships. Some of these Roman students have even visited their friends in the U.S., including on two official English Summer Camps that Duquesne University created and hosted in Pittsburgh for the Einstein-Bachelet students in 2009 and 2011.

I was recently at a wedding in Rome between one of our American alumnae and her now-Roman husband who she met during her semester abroad when a young man came up to me and said, “Are you Professor Michael?” I responded that I was. He told me that he had participated in our program and it changed his life. He was still friends with his partners from years before and he had understood the value of his city through the eyes of our American students. It helped to inspire him, as he was currently running for public office in Rome to help make his city a better place.

The main feature that differentiates your work from other study abroad programs are the project by which you bring American and Italian students to the Sicily Rome American Cemetery and Memorial in Nettuno, south of Rome...

(Alana Sacriponte) Our academic offerings have always been, and remain to be the keystone of our program, including on-site art history and classical history courses that are taken in the city center, with Rome as their open-air classroom. However, something that we thought was lacking was the academic opportunity to describe, analyze, and evaluate the cultural experiences students were having in Italy and with local, Italian people.

Many tourists and visitors learn the cultural nuances of Italy, like how Italians don’t order a cappuccino after meals and not cutting spaghetti with a knife, but we wanted to provide a means to deepen intercultural exploration. By clarifying cultural confusions, learning about oneself and one’s own culture, as well as gaining a depth of the new Italian culture, we can help students reflect on their experiences and observations from different intercultural perspectives.

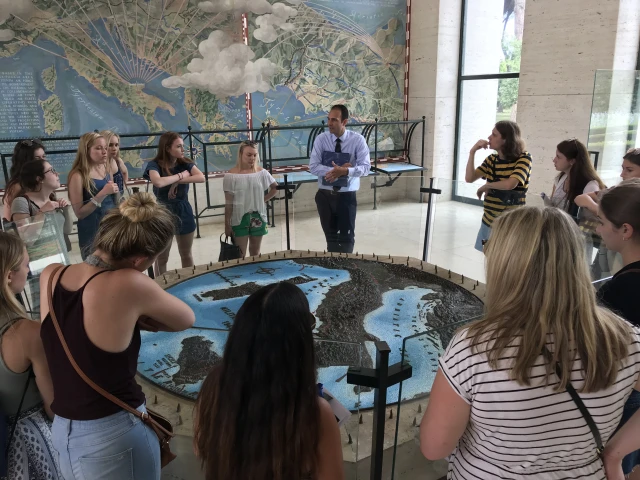

In 2013, we developed a 3-part Intercultural Engagement course series that students would take prior, during, and after the study abroad experience. The course that the Duquesne in Rome students take while abroad is called “Intercultural Awareness and Exploration” and is co-taught by Michael Wright and myself. We use these class hours to reflect on the students’ experiences with their Italian partners at the Einstein-Bachelet high school and meet with diverse underrepresented communities in Rome with visits and lectures by historian and guide Micaela Pavoncello from the Roman-Jewish community and Ahmad Ejaz from the Islamic Cultural Centre of Italy. But I think that the most fulfilling experience for all students is their work on the “Be the Difference - Never Again” project, which we implemented in 2016 as a part of the course.

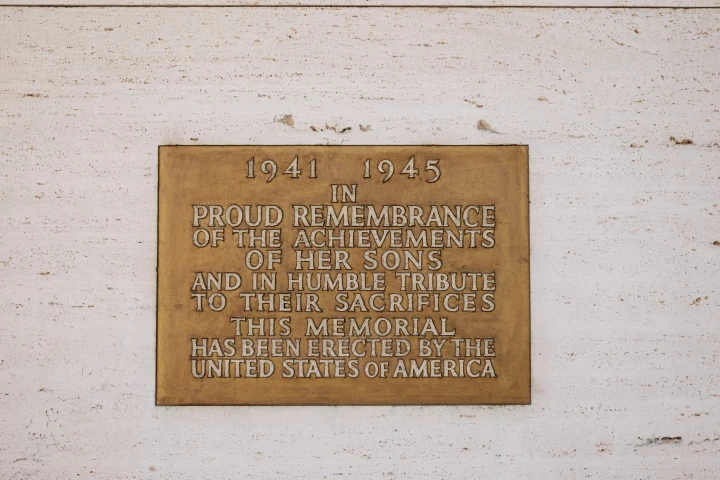

(Michael Wright) Early in 2016, I received a phone call from a friend and fellow U.S. study abroad program director in Florence who told me of an American friend of his, Elizabeth Bettina, who had written a book on her family’s village near Salerno that had been the site of a Jewish internment camp during World War II. He had been using her book in his curriculum and she was coming to Italy, interested in visiting the two American war cemeteries in Italy, including the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery in Nettuno, just south of Rome near Anzio.

Elizabeth arrived in Rome and I accompanied her down the Tyhrannean coast on a beautiful spring morning. I had read her book and embarrassingly admitted to her that I had been to Nettuno many times to eat seafood and go to the beach with Roman friends, but I had never visited the cemetery where 11,000 U.S. American service members were entombed or memorialized.

Melanie Resto, Superintendent of the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery welcomed and created special tours for us. As we entered this sacred, giant site that was studded with gleaming marble crosses and Stars of David tombs, sheltered by the towering umbrella pines of Rome, we moved with our guide through the 77-acre property hearing the harrowing stories of the young men and women who laid at rest. We saw an elderly man in his 90s laying roses at different tombs. Our guide told us that he was a local man who had been friends with the soldiers, played baseball with them, and even was able to go on fighting missions with them, until his soldier friends were ambushed and killed. Since then, he has come once a week to lay flowers at his friends’ graves.

We learned the personal story of the group of soldiers who had been killed and were missing that Sophia Loren speaks of in her memoire, and how one of them was a soldier who helped care for a scar on her face that she had received during the war. She owed her beauty to him. We then heard the heart-wrenching stories of those who had sacrificed their lives, learning that many of these soldiers have never received visits from their loved ones after the war.

Elizabeth and I were moved beyond words. As we drove back to the city, Elizabeth spoke of her vision for U.S. American students to visit these cemeteries during their semester abroad and to learn the stories of those who had given their lives for freedom. She called this the “Be the Difference – Never Again Project”. A light bulb went off in my mind, thinking that this might be the perfect project for our Intercultural Awareness course and to create a more meaningful collaboration for our Duquesne/Einstein-Bachelet relationship.

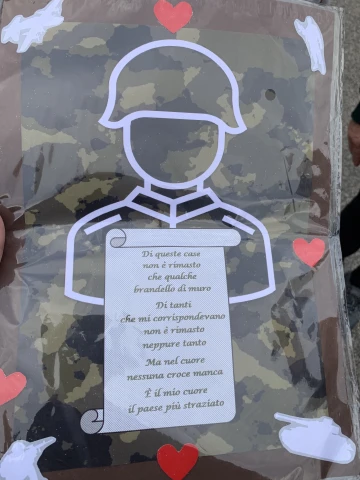

Alana and I talked about how it would be perfect for them to work together in small groups, each assigned a soldier at the cemetery to research. The Duquesne students could take the lead with military records and online searches to reconstruct the stories of these young soldiers, including collecting historic pictures and newspaper articles. The Einstein-Bachelet students in each group would work with the research to create a homage to their soldier, through poetry and song. The project would culminate at the end of the semester with a visit to the cemetery. The students would help to create a memorial service that we all participate in, take tours of the cemetery, and ultimately go to find the tomb of their U.S. American soldier to present their homage at their grave. Ultimately, students would turn in their group projects of research and homage, which we would donate to the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery.

Seven years have passed since the inception of the “Be the Difference-Never Again” project at Duquesne in Rome. Students learn intercultural values from working together and creating friendships, while coming into contact with important historical material. At the beginning of the semester, we reiterate that this is not a political project to show that America “saved” Italy, but rather an experiential collaboration to highlight the important relationship and friendship that our two countries have had over the past 80 years. It reminds us that because of combined efforts by the Allied forces and the Italian partisans, that Rome is the free and beautiful city where we make our homes, even if only for a semester for our Duquesne students. Einstein-Bachelet student, Enrico Mottola, reflected, “This experience has touched me deeply and made me think of the value of sacrifice, something these soldiers did for Italy and Europe.”

If it is possible, I would ask you to tell some anecdotes or the details of some stories that particularly struck you and your students, studying someone of the nearly 11,000 American heroes buried or celebrated in Nettuno, who gave their lives to free our country.

(Michael Wright) An experience that connected the Duquesne and Einstein-Bachelet students even beyond the borders of Italy with this project was a group of students that had been assigned First Lieutenant Chester Angell as their soldier. Since students only receive the soldier’s military record, including their name, place of enlistment, and their serial number, it is up to the students to find out who the “real” Chester was. On a genealogy website, the students found the email address of someone who looked to be a possible living relative. They vulnerably reached out to Chester’s living niece, Barbara Chiarella who lives in Colorado.

The group of students received an emotional and joyous response, helping the students know Chester more fully. They learned that he had been adopted by the Angell family as a child and had learned to be a pilot after enlisting with the Army Air Corp in November 1941. Before being sent to war, he had been a flight instructor on Beechcraft AT-11 planes and Martin B-26 bombers in the southern United States. He married his sweetheart Elaine Brown in June 1942 and they had their beloved daughter Janice in July 1943. In early 1944, he was assigned to the 37th Bomb Squad, 17th Bombardment Group, which had been credited through strategic bombings to have saved much of the art and architecture in Florence. Chester was stationed in Sardinia. Just days before dying in battle, he wrote an optimistic letter to his father, “It’s a mite rough in spots but I’ll get along all right...I’ve got a darn good crew.”

Chester died on March 16, 1944. Chester’s niece told the students that he is remembered in their family as “a young, handsome, and intelligent hero in so many ways.” Chester’s niece Barbara wrote me an emotional email saying, “May I just say that the program you created is not only a testament to humanity, history, and our fallen soldiers, it has personally given me a whole heart. Chester was a special brother to my father [Donald], which prompted my visit to Nettuno in 2009 to pay homage to both Chester and Donald, as brothers whose relationship was ended too soon.” The “Be the Difference-Never Again” project not only connects the living to the heroic dead, but connects the living with the living, creating hope for a more peaceful future.

(Alana Sacriponte) This April 2023 will be the first time that one of our students has a family member buried at the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery and whom we will honor during our ceremony. Physician Assistant student from the Rangos School of Health Sciences, Megan Stevens and her group will be paying homage to her great-uncle Alfred W. Graham, who was a pilot in the 30th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division in the U.S. Army. He was killed on January 31st, 1944 and was awarded a Purple Heart for his bravery.

You educate kids who are developing their personalities and have their whole lives ahead of them, and you rightly confront them with a history that concerns events that happened almost 80 years ago now. I think that what you do is very useful, because this experience teaches them more than many hours of theory… am I wrong?

(Michael Wright) Theory is obviously an important part of the Intercultural Awareness course that Alana and I teach, but we are blessed to have Rome and Italy be a living laboratory where our students can see theory put into practice. The “Be the Difference-Never Again” project helps us do this. Both Duquesne and the Einstein-Bachelet students have the opportunity to dive deeper into cultural and historical exploration. They understand each other better by developing linguistic and cultural understanding to create lasting friendships.

They also learn the consequences of war, what freedom means, the plight of the solider, and how to bring this 80-year history forward to our contemporary, broken world. They learn that even though Italian statehood may be younger than that of the United States, it is a peninsula full of ancient, rich, and complex history. These complexities not only change their lives in the “now” as study abroad students, but changed many of their lives long ago when their great-grandparents or grandparents decided to emigrate to the United States. Through our semester-long program, Duquesne students are able to shed their initial romantic notion of Italy through authentic experiences. They take away a mature understanding and love for Italy in its successes, its challenges, and its always hopeful future.

Most likely among our readers are descendants of a family of some of the 11,000 American heroes buried or celebrated at the Sicily Rome American Cemetery and Memorial, among whom are many names ending in a vowel. What would you feel like telling them?

(Michael Wright) We want those who have family who are buried at the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery to know that we continue to work through the list of 11,000 names. Young Italian and U.S. American students are taking the time to learn the stories of those who sacrificed to help free Italy. Your loved ones are not just a name on a tomb or a serial number on the west coast of Italy, but we know that they were living young people, who had families, were loved and missed terribly when they did not come home. We honor them with the “Be the Difference-Never Again” project, allowing their stories and sacrifice to bring perspective and change to our students. We hope the bringing-to-life of their stories will create an urgency for peace in these young people at a time when there is war again on the continent of Europe.

Questa nuova intervista mi è particolarmente cara per tre motivi. Il primo è che racconta di come anche i giovani italiani possono essere guidati a conoscere il sacrificio che migliaia di eroi americani hanno fatto per liberare l'Italia. Il secondo è che molto spesso mi vengono suggerite interviste che non sono esattamente nel flow di questa rubrica, che esplora cose e persone e storie nuove e particolari: per cui per gli ospiti di oggi devo ringraziare la nostra comune amica Elizabeth Bettina, che ci ha presentati.

Il terzo motivo è che quasi sempre le mie interviste sono dedicate interamente a qualcosa del passato, storie di un tempo; oppure interamente a storie del presente e del futuro. E’ difficile che abbiano insieme passato e futuro. Ma stavolta questo è proprio quello che accade. Per cui do molto volentieri il benvenuto su We the Italians a Michael Wright e Alana Sacriponte, che gestiscono il programma di study abroad qui a Roma della Duquesne University.

Vorrei iniziare chiedendovi di parlare ai nostri lettori del programma di studio all'estero della Duquesne University qui a Roma. Chi sono i vostri studenti, da dove vengono, cosa studiano in Italia?

(Michael Wright) La Duquesne University è un'università privata cattolica di tradizione spirituale situata a Pittsburgh, PA, con un campus internazionale a Roma. Il 2021 ha segnato il 20° anniversario del campus della Duquesne a Roma, dove ogni anno ospitiamo 200 studenti nella nostra bellissima proprietà che condividiamo con le Suore della Sacra Famiglia di Nazareth nella verdeggiante Riserva Naturale dell'Acquafredda di Roma, vicino all'affollato quartiere popolare di Boccea.

Il campus di Roma ospita per un semestre o un programma estivo studenti provenienti dalle nove scuole dell'Università. I semestri accademici sono pieni di studenti universitari che lavorano sui loro corsi di base in aree come la storia dell'arte, la storia classica, la teologia, la sociologia, gli studi interculturali, la lingua italiana, insieme a corsi di specializzazione in educazione, economia e scienze. Per gli studenti della Duquesne, molte di queste materie prendono letteralmente vita studiando l'arte e l'archeologia nei luoghi in cui sono avvenute.

I nostri programmi estivi sono pieni di studenti universitari e laureati che studiano musica, infermieristica e fisioterapia, fornendo un contesto storico e un confronto con la sanità che speriamo renda gli studenti della Duquesne competitivi nelle loro future carriere accademiche e professionali.

Avete studenti italoamericani? Qualche mese fa ho iniziato a sviluppare una teoria, ovvero che i ragazzi italoamericani sono differenti dai ragazzi americani di altre etnie, e ovviamente differenti dai ragazzi italiani. Cosa ne pensate?

(Alana Sacriponte) Ci sono più di 1,4 milioni di italoamericani nello Stato della Pennsylvania e più del 15% delle persone si identifica come italoamericano nella Pennsylvania occidentale, dove si trova il nostro campus. Ma chi ha visitato Pittsburgh, penserà che il numero sia ancora più alto! L'Heinz History Center di Pittsburgh possiede una delle più grandi collezioni e archivi di cultura materiale italoamericana. Abbiamo anche una Little Italy, a Bloomfield, e molte altre aree italiane "non ufficiali", come lo Strip District, dove regna l'orgoglio italiano. Ci sono tantissimi festival italiani in tutta Pittsburgh e nei sobborghi, come il Kennywood Day italiano (il nostro parco a tema locale), e una scena locale di caffè e ristoranti che mette in risalto il cibo italiano e l'esperienza italiana.

Direi che più della metà degli studenti della Duquesne University che vengono a studiare nel nostro campus di Roma sono italoamericani, e questa esperienza è molto diversa per loro rispetto agli altri compagni di classe. L'esperienza complessiva è la stessa, in quanto si confrontano con l'incredibile patrimonio culturale italiano, come l'arte, il cibo, la lingua e la musica. Ma gli studenti italoamericani che vengono anche in cerca di un patrimonio culturale, vivono un'esperienza che li porta a fare i conti con il loro passato e a provare emozioni forti nel tornare nel luogo d'origine della loro famiglia. Questo è probabilmente uno dei punti salienti del mio lavoro: aiutare gli studenti italoamericani a pianificare i loro viaggi nei piccoli e remoti villaggi dei loro bisnonni, o chiedere il mio aiuto per tradurre il primo incontro con i parenti italiani durante il loro semestre all'estero. Parenti lontani che non hanno mai incontrato, spesso con una grande barriera linguistica, non possono ostacolare questo pellegrinaggio quasi sacro per questi studenti. Gli studenti visiteranno luoghi incredibili come Venezia, Firenze e la Costiera Amalfitana, ma nulla sarà mai paragonabile all'esperienza di vedere la chiesa in cui è stato battezzato il loro bisnonno, o di incontrare un cugino o un prozio di cui hanno sentito parlare nei racconti delle loro famiglie da quando sono nati.

So che personalmente sono molto coinvolta nell'aiutare questi studenti, non solo come parte del mio lavoro, ma perché quella storia è anche la mia. Quando ho studiato all'estero nel 2003 nell'ambito di questo stesso programma, come studentessa universitaria alla Duquesne, ho incontrato il cugino di primo grado di mio nonno. È stata un'esperienza molto toccante per me sentirmi in contatto con il suo passato, conoscere meglio la mia famiglia e sentire un legame autentico con questo Paese che è stato una parte così importante della mia vita e delle mie tradizioni.

Circa i nostri studenti italoamericani, credo che la storia più memorabile sia stata quella di un ex studente che aveva la famiglia in Abruzzo, in una piccola città vicino a Pescara. Non li aveva mai incontrati prima, ma erano così entusiasti del fatto che sarebbe stato a Roma per tre mesi che, al suo arrivo, la sua prozia ha preso un autobus con un viaggio di tre ore da Pescara a Roma, poi la metropolitana e l'autobus locale per raggiungerlo al campus. Nel suo lungo viaggio, ha portato con sé due teglie di melanzane alla parmigiana, euro in contanti nel caso in cui lui non ne avesse, e ha continuato a farlo una volta al mese mentre lui era qui. Sua zia mi ha detto che sentiva il dovere di assicurarsi che fosse ben nutrito e di controllarlo, quasi come se ne avesse preso la custodia mentre era sul suolo italiano. È stata una cosa bellissima da vedere.

Mi piace molto il rapporto che avete instaurato con un liceo romano vicino al vostro campus. In base alla vostra esperienza, cosa imparano i ragazzi italiani da questo scambio e cosa imparano i ragazzi americani?

(Michael Wright) Il rapporto tra la Duquesne di Roma e il liceo I.I.S. Einstein-Bachelet è iniziato nel 2005, quando nel 2004 abbiamo trasferito la sede del campus nell'attuale quartiere Boccea di Roma. Il liceo Einstein-Bachelet si trova a meno di un chilometro dalla nostra sede. Ho continuato a vedere altri programmi universitari statunitensi a Roma e a Firenze offrire reciprocità alle loro comunità attraverso spettacoli musicali, installazioni artistiche presso scuole e ospedali locali e sfilate di moda di creazioni degli studenti.

Stavo pensando a come coinvolgere maggiormente i nostri studenti nel nostro quartiere e a come restituire qualcosa alla città che ci ospita gentilmente come americani. Un giorno, passando davanti al liceo, ho pensato: "Mi chiedo se potremmo creare uno scambio con gli studenti che stanno imparando l'inglese al liceo per aiutarli a migliorare le loro competenze linguistiche e, a loro volta, potrebbero aiutare i nostri studenti che stanno imparando l'italiano". Dopo tutto, gli studenti italiani hanno 19 o 20 anni e frequentano l'ultimo anno di scuola superiore, mentre i nostri studenti hanno per lo più 19 e 20 anni e frequentano il secondo anno di università.

Un incontro entusiasta con il dipartimento di lingua inglese ha portato a un gemellaggio ufficiale che è in vigore da allora. Negli ultimi 18 anni, il rapporto tra Duquesne e il liceo Einstein-Bachelet ha portato quasi 1.000 studenti di Duquesne a lavorare con quasi 1.000 loro coetanei romani su progetti che hanno creato molte amicizie durature. Alcuni di questi studenti romani hanno persino visitato i loro amici negli Stati Uniti, anche in occasione di due campi estivi ufficiali di inglese che la Duquesne University ha creato e ospitato a Pittsburgh per gli studenti dell'Einstein-Bachelet nel 2009 e nel 2011.

Di recente ho assistito a un matrimonio a Roma tra una nostra ex alunna americana e il suo attuale marito romano, conosciuto durante il suo semestre all'estero, quando un giovane si è avvicinato e mi ha chiesto: "Lei è il professor Michael?". Ho risposto di sì. Mi disse che aveva partecipato al nostro programma e che gli aveva cambiato la vita. Era ancora amico dei suoi compagni di anni prima e aveva capito il valore della sua città attraverso gli occhi dei nostri studenti americani. Questo ha contribuito a ispirarlo, visto che attualmente si sta candidando per una carica pubblica a Roma per contribuire a rendere la sua città un posto migliore.

La caratteristica principale che differenzia il vostro lavoro dagli altri programmi di studio all'estero è il progetto con cui portate gli studenti americani e italiani al Sicily Rome American Cemetery and Memorial di Nettuno, a sud di Roma...

(Alana Sacriponte) Le nostre offerte accademiche sono sempre state, e rimangono, la chiave di volta del nostro programma, compresi i corsi di storia dell'arte e di storia classica che si tengono nel centro della città, con Roma come aula all'aperto. Tuttavia, ci è sembrato che mancasse l'opportunità accademica di descrivere, analizzare e valutare le esperienze culturali che gli studenti stavano vivendo in Italia e con gli italiani del posto.

Molti turisti e visitatori imparano le sfumature culturali dell'Italia, come il fatto che gli italiani non ordinano il cappuccino dopo i pasti e non tagliano gli spaghetti con il coltello, ma noi volevamo fornire un mezzo per approfondire l'esplorazione interculturale. Chiarendo le confusioni culturali, imparando a conoscere se stessi e la propria cultura e approfondendo la nuova cultura italiana, possiamo aiutare gli studenti a riflettere sulle loro esperienze e osservazioni da diverse prospettive interculturali.

Nel 2013 abbiamo sviluppato una serie di corsi sull'impegno interculturale in tre parti che gli studenti avrebbero seguito prima, durante e dopo l'esperienza di studio all'estero. Il corso che gli studenti della Duquesne in Rome seguono durante l'esperienza all'estero si chiama "Intercultural Awareness and Exploration" ed è tenuto da me e Michael. Utilizziamo queste ore di lezione per riflettere sulle esperienze degli studenti con i loro partner italiani al liceo Einstein-Bachelet e per incontrare le diverse comunità sottorappresentate a Roma con visite e conferenze della storica e guida Micaela Pavoncello della comunità ebraico-romana e di Ahmad Ejaz del Centro culturale islamico d'Italia. Ma credo che l'esperienza più appagante per tutti gli studenti sia il loro lavoro sul progetto "Be the Difference - Never Again", che abbiamo realizzato nel 2016 come parte del corso.

(Michael Wright) All'inizio del 2016, ho ricevuto una telefonata da un amico e direttore di un programma di studio all'estero americano a Firenze, che mi ha parlato di una sua amica americana, Elizabeth Bettina, che aveva scritto un libro sul villaggio della sua famiglia vicino a Salerno, che era stato sede di un campo di internamento per ebrei durante la Seconda guerra mondiale. Il suo libro era stato utilizzato nel suo programma di studi e lei stava venendo in Italia, interessata a visitare i due cimiteri di guerra americani in Italia, tra cui il Sicily-Rome American Cemetery di Nettuno, appena a sud di Roma, vicino ad Anzio.

Elizabeth arrivò a Roma e io l'accompagnai lungo la costa tirrenica in una bella mattina di primavera. Avevo letto il suo libro e le avevo confessato con imbarazzo di essere stata molte volte a Nettuno per mangiare frutti di mare e andare in spiaggia con amici romani, ma non avevo mai visitato il cimitero dove sono stati sepolti o commemorati 11.000 membri del servizio americano.

Melanie Resto, sovrintendente del Sicily-Rome American Cemetery, ci ha accolti e ha creato un tour speciale per noi. Entrando in questo luogo sacro e gigantesco, costellato di croci di marmo scintillanti e tombe con stelle di David, al riparo degli imponenti pini di Roma, ci siamo mossi con la nostra guida attraverso la proprietà di 77 acri, ascoltando le storie strazianti dei giovani uomini e donne che lì riposavano per sempre. Abbiamo visto un uomo anziano di 90 anni che deponeva rose su diverse tombe. La nostra guida ci ha raccontato che era un uomo del posto che era stato amico dei soldati, aveva giocato a baseball con loro e aveva persino potuto partecipare a missioni di combattimento con loro, fino a quando i suoi amici soldati erano caduti in un'imboscata e uccisi. Da allora, viene una volta alla settimana a deporre fiori sulle tombe dei suoi amici.

Abbiamo appreso la storia personale del gruppo di soldati uccisi e dispersi di cui parla Sophia Loren nel suo memoriale, e di come uno di loro fosse un soldato che l'aveva aiutata a curare una cicatrice sul viso che aveva ricevuto durante la guerra. A lui doveva la sua bellezza. Abbiamo poi ascoltato le storie strazianti di coloro che hanno sacrificato la loro vita, apprendendo che molti di questi soldati non hanno mai ricevuto visite dai loro cari dopo la guerra.

Elizabeth e io ci siamo molto commossi. Mentre tornavamo in città, Elizabeth ha parlato della sua visione di far visitare questi cimiteri agli studenti americani durante il loro semestre all'estero e di conoscere le storie di coloro che hanno dato la vita per la libertà. Ha chiamato questo progetto "Be the Difference - Never Again". Mi si è accesa una lampadina nella mente, pensando che questo potrebbe essere il progetto perfetto per il nostro corso di consapevolezza interculturale e per creare una collaborazione più significativa per il nostro rapporto Duquesne/Einstein-Bachelet.

Alana e io abbiamo parlato di come sarebbe stato perfetto per loro lavorare insieme in piccoli gruppi, assegnando a ciascuno un soldato del cimitero da ricercare. Gli studenti della Duquesne avrebbero potuto prendere l'iniziativa con i registri militari e le ricerche online per ricostruire le storie di questi giovani soldati, raccogliendo anche foto storiche e articoli di giornale. Gli studenti dell'Einstein-Bachelet di ciascun gruppo avrebbero lavorato con la ricerca per creare un omaggio al loro soldato, attraverso poesie e canzoni. Il progetto culmina alla fine del semestre con una visita al cimitero. Gli studenti avrebbero contribuito a creare un servizio commemorativo a cui tutti avrebbero partecipato, avrebbero visitato il cimitero e infine sarebbero andati a cercare la tomba del loro soldato americano per presentare il loro omaggio sulla tomba. Alla fine, gli studenti consegnano i loro progetti di ricerca e di omaggio, che sono donati al Sicily-Rome American Cemetery.

Sono passati sette anni dall'inizio del progetto "Be the Difference-Never Again" alla Duquesne di Roma. Gli studenti imparano i valori interculturali lavorando insieme e creando amicizie, entrando nel contempo in contatto con materiale storico importante. All'inizio del semestre, ribadiamo che non si tratta di un progetto politico per dimostrare che l'America ha "salvato" l'Italia, ma piuttosto di una collaborazione esperienziale per sottolineare l'importante rapporto e l'amicizia che i nostri due Paesi hanno avuto negli ultimi 80 anni. Ci ricorda che grazie agli sforzi congiunti delle forze alleate e dei partigiani italiani, Roma è la città libera e bella in cui viviamo, anche se solo per un semestre per i nostri studenti della Duquesne. Lo studente del liceo Einstein-Bachelet Enrico Mottola ha condiviso con noi questa riflessione: "Questa esperienza mi ha toccato profondamente e mi ha fatto pensare al valore del sacrificio, che questi soldati hanno fatto per l'Italia e per l'Europa".

Se è possibile, vi chiederei di raccontare qualche aneddoto o i dettagli di qualche storia che ha colpito particolarmente voi e i vostri studenti, studiando qualcuno dei quasi 11.000 eroi americani sepolti o celebrati a Nettuno, che hanno dato la vita per liberare il nostro Paese

(Michael Wright) Un'esperienza che ha collegato gli studenti della Duquesne e dell'Einstein-Bachelet anche oltre i confini dell'Italia con questo progetto è stata quella di un gruppo di studenti a cui era stato assegnato come soldato il Primo Tenente Chester Angell. Poiché gli studenti ricevono solo il libretto militare del soldato, con il nome, il luogo di arruolamento e il numero di matricola, spettava agli studenti scoprire chi fosse il "vero" Chester. Su un sito web di genealogia, gli studenti hanno trovato l'indirizzo e-mail di una persona che sembrava essere un possibile parente in vita. Hanno contattato la nipote vivente di Chester, Barbara Chiarella, che vive in Colorado.

Il gruppo di studenti ha ricevuto una risposta emotiva e gioiosa, che ha aiutato gli studenti a conoscere meglio Chester. Hanno appreso che da bambino era stato adottato dalla famiglia Angell e che aveva imparato a fare il pilota dopo essersi arruolato nell'Army Air Corp nel novembre 1941. Prima di essere inviato in guerra, era stato istruttore di volo su aerei Beechcraft AT-11 e bombardieri Martin B-26 negli Stati Uniti meridionali. Nel giugno 1942 sposò la donna di cui era innamorato, Elaine Brown, e nel luglio 1943 nacque la loro amata figlia Janice. All'inizio del 1944 fu assegnato al 37° gruppo artificieri, 17° Bombardment Group, che grazie ai bombardamenti strategici aveva salvato gran parte dell'arte e dell'architettura di Firenze. Chester era di stanza in Sardegna. Pochi giorni prima di morire in battaglia, scrisse una lettera ottimistica a suo padre: "È un po' dura a tratti, ma me la caverò... ho un equipaggio dannatamente buono".

Chester morì il 16 marzo 1944. La nipote di Chester ha detto agli studenti che nella loro famiglia è ricordato come "un eroe giovane, bello e intelligente sotto molti aspetti". La nipote di Chester, Barbara, mi ha scritto un'e-mail commossa: "Posso solo dire che il programma che avete creato non è solo una testimonianza dell'umanità, della storia e dei nostri soldati caduti, ma personalmente l’ho apprezzato con tutto il mio cuore. Chester era un fratello speciale per mio padre [Donald], il che mi ha spinto a recarmi a Nettuno nel 2009 per rendere omaggio sia a Chester che a Donald, come fratelli il cui rapporto è finito troppo presto". Il progetto "Be the Difference-Never Again" non solo collega i vivi agli eroi caduti, ma collega anche i vivi con i vivi, creando la speranza di un futuro più pacifico.

(Alana Sacriponte) Questo aprile 2023 sarà la prima volta che uno dei nostri studenti avrà un familiare sepolto nel Sicily-Rome American Cemetery, che onoreremo durante la nostra cerimonia. Megan Stevens, studentessa assistente medico della Rangos School of Health Sciences, e il suo gruppo renderanno omaggio al suo prozio Alfred W. Graham, che era un pilota del 30° reggimento di fanteria, 3° divisione di fanteria dell'esercito americano. Fu ucciso il 31 gennaio 1944 e gli fu conferito una medaglia Purple Heart per il suo coraggio.

Voi educate ragazzi che stanno sviluppando la loro personalità e hanno tutta la vita davanti a sé, e li mettete giustamente di fronte a una storia che riguarda eventi accaduti ormai quasi 80 anni fa. Credo che quello che fate sia molto utile, perché questa esperienza insegna loro più di tante ore di teoria... mi sbaglio?

(Michael Wright) La teoria è ovviamente una parte importante del corso di Intercultural Awareness che io e Alana teniamo, ma abbiamo la fortuna di avere Roma e l'Italia come laboratorio vivente dove i nostri studenti possono vedere la teoria messa in pratica. Il progetto "Be the Difference-Never Again" ci aiuta in questo senso. Sia gli studenti della Duquesne che quelli dell'Einstein-Bachelet hanno l'opportunità di approfondire la loro esplorazione culturale e storica. Si capiscono meglio sviluppando la comprensione linguistica e culturale per creare amicizie durature.

Imparano anche le conseguenze della guerra, il significato di libertà, la condizione del soldato e come portare avanti questa storia di 80 anni nel nostro difficilissimo mondo contemporaneo. Imparano che, anche se lo Stato italiano è più giovane di quello degli Stati Uniti, è una penisola piena di storia antica, ricca e complessa. Queste complessità non solo cambiano le loro vite nel "presente" come studenti all'estero, ma hanno cambiato molte delle loro vite molto tempo fa, quando i loro bisnonni o nonni hanno deciso di emigrare negli Stati Uniti. Grazie al nostro programma semestrale, gli studenti di Duquesne sono in grado di liberarsi dell'iniziale idea romantica dell'Italia attraverso esperienze autentiche. Ne traggono una comprensione e un amore maturi per l'Italia nei suoi successi, nelle sue sfide e nel suo futuro sempre pieno di speranza.

Molto probabilmente tra i nostri lettori ci sono i discendenti di una famiglia di alcuni degli 11.000 eroi americani sepolti o celebrati al Sicily Rome American Cemetery and Memorial, tra i quali ci sono molti nomi che terminano con una vocale. Cosa vi sentite di dire loro?

(Michael Wright) Vogliamo che coloro che hanno parenti sepolti al Sicily-Rome American Cemetery sappiano che continuiamo a lavorare sulla lista degli 11.000 nomi. Giovani studenti italiani e statunitensi stanno dedicando il loro tempo a conoscere le storie di coloro che si sono sacrificati per aiutare l'Italia a liberarsi. I vostri cari non sono solo un nome su una tomba o un numero di matricola sulla costa occidentale dell'Italia, ma sappiamo che erano giovani vivi, che avevano una famiglia, che sono stati amati e che sono mancati terribilmente quando non sono tornati a casa. Li onoriamo con il progetto "Be the Difference-Never Again", permettendo alle loro storie e al loro sacrificio di portare prospettiva e cambiamento ai nostri studenti. Speriamo che, dando vita alle loro storie, si crei in questi giovani un'urgenza di pace in un momento in cui c'è di nuovo la guerra nel continente europeo.