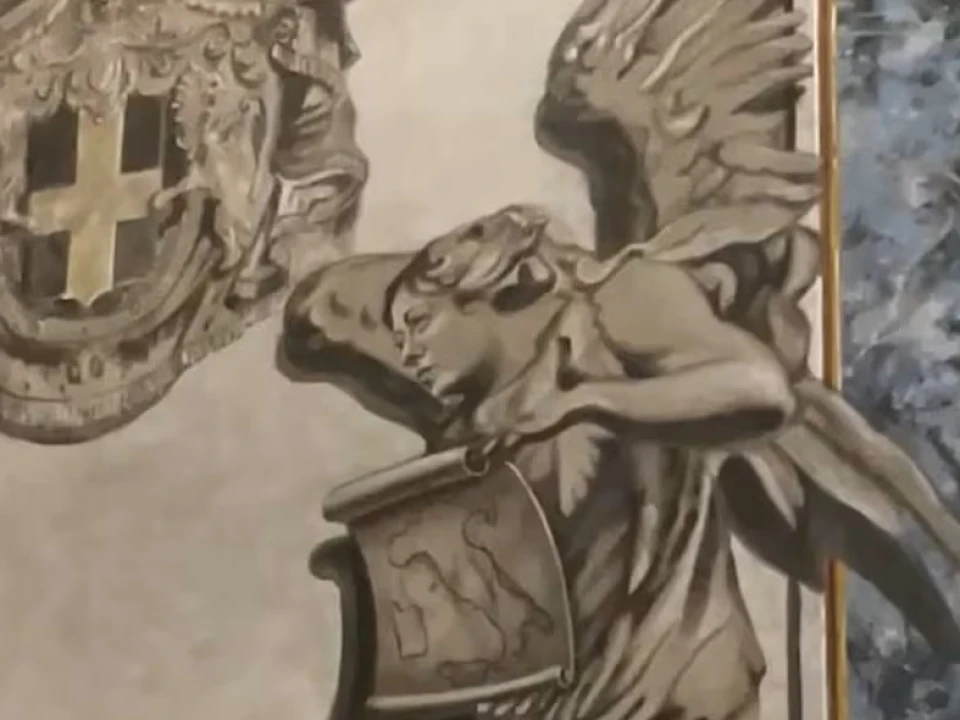

In Rome’s Basilica of San Lorenzo in Lucina, a restored fresco angel briefly drew worldwide attention because its face appeared to resemble Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni. The chapel artwork, part of a restoration project after water damage, was meant to show two angels but one was widely seen as bearing a striking likeness to Meloni, sparking political debate and crowds visiting the church out of curiosity rather than for worship.

Italian media reported that Italy’s culture ministry and the Diocese of Rome opened inquiries into the incident, stressing that sacred art shouldn’t be politicized. Amid the uproar and on instructions from church authorities, the controversial face was painted over and removed. Meloni herself joked on social media that she definitely doesn’t resemble an angel.

This gives us an excuse to talk a little bit about “arte sacra” (sacred art) in Italy, which is an extraordinary, incredible, unevaluable part of Italian art.

Sacred art in Italy represents one of the most important and recognizable cores of the nation’s cultural heritage. The term “sacred art” refers to the body of artistic works – painting, sculpture, architecture, and the applied arts – created for religious purposes, particularly those connected with Christian worship. In Italy, more than anywhere else, this form of artistic production has continuously accompanied the country’s history, becoming an essential instrument of spiritual, political, and cultural communication. Sacred art was not created to be admired in the modern aesthetic sense, but to speak to the faithful, convey values, recount biblical episodes, and make the divine visible through forms accessible to all.

For centuries, sacred art therefore had a primarily didactic function. In a largely illiterate society, images and symbols replaced the written word: frescoes, altarpieces, and sculptures narrated the life of Christ, the Virgin, and the saints, illustrated good and evil, the reward of salvation and the punishment of sin. At the same time, these works helped create a strong sense of collective identity, linking the local community to its church, its patron saint, and its own history.

For a very long time, the main financier of sacred art in Italy was the Catholic Church. Popes, cardinals, bishops, monasteries, and religious orders commissioned an enormous number of works, using economic resources derived from donations, tithes, and land revenues. Alongside the Church, the great aristocratic and bourgeois families played a central role, using artistic patronage to assert their social and political prestige. Financing a chapel, an altar, or a cycle of frescoes meant leaving a lasting mark, often accompanied by coats of arms, portraits, or monumental tombs. Families such as the Medici in Florence, the Este in Ferrara, or the Gonzaga in Mantua turned sacred art into a powerful tool for representing their authority.

Civil institutions and professional guilds also participated in patronage. Medieval communes, lay confraternities, and craft corporations financed works destined for city churches, strengthening the bond between religious life and civic life. In this sense, Italian sacred art is also the result of a continuous collaboration between faith, politics, and economics.

Sacred artworks are primarily displayed in the places for which they were conceived: churches, cathedrals, basilicas, abbeys, and sanctuaries. Italy is a widespread museum, where absolute masterpieces are still found in their original context, integrated with architecture and liturgy. However, from the modern era onward, and especially during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, many works were transferred to museums for reasons of conservation or security. The Vatican Museums, the Uffizi Galleries, the Pinacoteca di Brera, and the Capodimonte Museum today preserve important examples of sacred art, allowing for broader public access and more in-depth study.

From a historical and artistic point of view, the masterpieces of Italian sacred art span all periods. In the Middle Ages, Byzantine influence is evident in the mosaics of Ravenna and Venice, where the use of gold and the rigidity of the figures express divine transcendence. With the fourteenth century, artists such as Giotto introduced a decisive turning point: sacred figures acquired volume, emotion, and humanity, as seen in the frescoes of the Basilica of Saint Francis in Assisi, which mark the beginning of a new conception of space and religious narrative.

The Renaissance represents the moment of greatest splendor of Italian sacred art. During this period, the search for harmony, ideal beauty, and formal perfection merged with spiritual content. Michelangelo, with the ceiling and the Last Judgment of the Sistine Chapel, created one of the highest syntheses of art, faith, and expressive power ever achieved. At the same time, Leonardo da Vinci interpreted the sacred in a profoundly human key, as in the Last Supper, where spiritual drama is reflected in the gestures and expressions of the apostles.

In the seventeenth century, with the Counter-Reformation, sacred art once again changed its appearance. The Church called for clearer, more engaging, and more emotional images, capable of directly affecting the faithful. In this context, Caravaggio emerged, bringing a raw and dramatic realism into sacred scenes, populated by saints and figures with popular features, immersed in strong contrasts of light and shadow. Baroque art transformed churches into theatrical spaces, where painting, sculpture, and architecture interacted to inspire wonder and devotion.

In conclusion, sacred art in Italy is not merely an artistic production linked to religion, but a continuous narrative of the country’s history. Through faith, patronage, locations, and masterpieces, it bears witness to the evolution of taste, power, and Italian society. Even today, this heritage continues to define Italy’s cultural landscape and represents one of the country’s most important contributions to the history of world art.