This February falls the one hundred year anniversary of the recording of the first Jazz song album ever recorded "Livery Stable Blues ", in the history of music. It was an Italian, James Dominick "Nick” La Rocca, who had this honor.

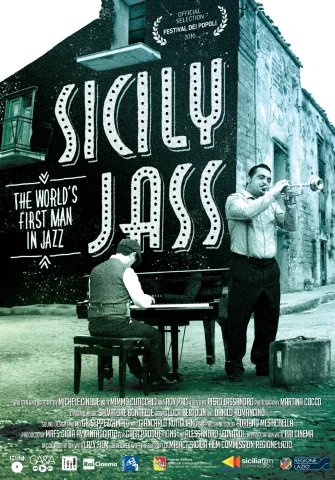

To celebrate this controversial artist, whom the great Renzo Arbore told us about when we met him, we speak with Michele Cinque, a young talented director and author of a splendid film/documentary that tells the story about the relationship between Sicilian Jazz, New Orleans Jazz and the emigration of Italians (especially Sicilians) to Louisiana.

Michele, you are the author of a small masterpiece, "Sicily Jass": the history of Nick La Rocca, the Sicilian who emigrated to New Orleans and one hundred years ago recorded the first ever Jazz record. Please tell us about "Sicily Jass"

The idea came to me while I was shooting a biographical film about the life of Louis Armstrong, one of the most famous black jazz musicians. Reading his first autobiography I came across Nick La Rocca.

After interviewing some great jazz critics in the United States, like Dan Morgenstern, for example, I came to understand the importance of this Sicilian jazz chromosome. There is not only Nick La Rocca, there were also Louis Prima, Leon Roppolo, and a whole generation of musicians who across two centuries contributed to the Italian and Sicilian gene that is present in jazz music.

I worked on this film for 3 years. It is a documentary film that is 73 minutes long and tells about the life of Nick La Rocca.

I decided to use an interview that had never been released, and that La Rocca gave in the 1950’s. The interview is also one of the reasons that La Rocca is almost forgotten in the history of music: there are very critical statements made in the interview. From my point of view, we can say that at the end of his life La Rocca had developed almost a psychosis, with respect to the character that I had learned to know and studied. He believed that all the merits that he had achieved, and everything he had helped to create jazz, had been removed, and the recognition given totally to African Americans. This is why he seems to have a beef with them. It was a period of struggle and claim for civil rights; these declarations made him an "inconvenient" character, which was seen very badly among the critics.

I tried to get as close as possible to the humanity of his character. The film travels on two tracks. The first is that of fiction, thanks to the exceptional narrator Mimmo Cuticchio, that guides the viewer through the recovery of the historical memory of this story, accompanied by Roy Paci on the trumpet, by Salvatore Bonafede on the piano and by Salemi’s band. Music for me is a narrative element, and not only a soundtrack.

The second track of the film is that of a documentary, and an in-depth historical survey that I conducted in the United States from New Orleans and from the archives of Washington.

It is therefore a "hybrid" film, part fiction and part documentary, whose structure was designed precisely to try to tell a very difficult story, the protagonist being a character dead over half of a century ago.

The film was finished a year and a half ago, and is now still being presented around international film festivals. It was presented in Rio de Janeiro and the New Orleans Film Festival in February 2016, and will be presented in Canada at the Victoria Film Festival, while in April 2017 I will be in the United States. So, at the moment the film hasn’t been distributed yet, but we are starting to think about producing the DVD and selling it through our film website.

Who was Nick La Rocca, and how did it happen that he was the first to record a jazz song?

La Rocca was born in New Orleans in 1896, and is the son of a shoemaker from Salaparuta, a small village in the province of Trapani. His Father Girolamo Rocca and mother Vita moved to New Orleans in about 1880: they were 2 of 30,000 Sicilians who lived in New Orleans at the beginning of the century.

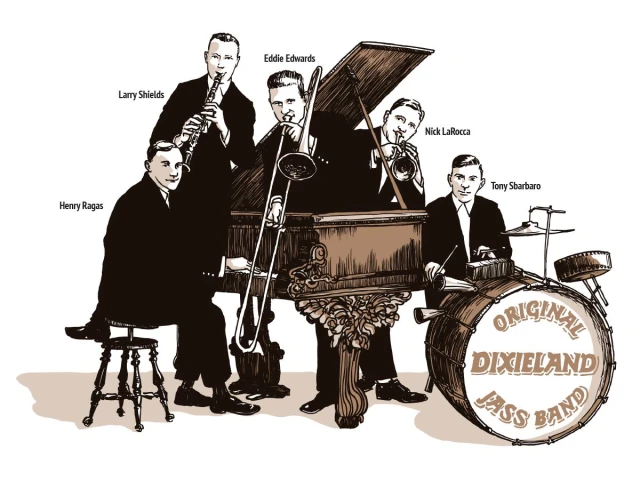

The Sicilian community was in contact with all the poorest levels of the population of New Orleans. There was a strong influence between Sicilian, Creole and African Americans: this is not what happened specifically to La Rocca, but much more to other characters that have made the history of the Italian or better Sicilian jazz in New Orleans. La Rocca was a difficult person: he is perhaps the first successful band leader, in fact one of the characters of the film defines his band, the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, the Beatles of the early 1900’s, the era of jazz.

La Rocca has a resounding success: in 1917 he will find himself in New York in one of the newest and most important "Victor" studios, to record the first jazz recording in history.

The story is a bit daring: he and his friend and partner Eddie Edwards were two electricians who played music as a hobby: like all the musicians of that era in New Orleans, they had another job. One day they were invited to Chicago in 1916 to play in a club, the “Shiller Café”, which was a place where gangsters use to gather. Their performance was a roaring success and Max Hart, an agent, took them to New York where they performed at Reisenweber at Columbus Circle, one of the most famous places where to perform at that time. They were so successful that a talent scout of Victor records offered them a contract to record in the studio, and two months later the band became the highest paid in the United States and sold 1 and a half million copies of the record in 1917.

In 1919 they were invited to play for the dance of the Armistice in England: thus they became one of the first American band to tour in Europe.

I am convinced that, in those years, the fact that the Original Dixieland Jazz Band was a white band certainly had an important weight on their success, with respect to other African American musicians very famous at the time in New Orleans, like Buddy Bolden, Kid Ory, and Bunk Johnson. La Rocca always denied that, and this was most probably one of the big problems that made him disliked and forgotten.

According to me, it is wrong to omit this part in telling the history of La Rocca, because in doing so you lose the humanity of the character: a son of a shoemaker from Salaparuta, who didn’t have the cultural tools to defend himself in the 50’s from jazz critics who had attended the best American universities. I wanted to represent a man who had a poor education, formed by the street life, who had learned to play "by ear", with a father who broke his trumpet because he didn’t want him to play: he believed that all musicians were beggars. In a way, this is a typical Italian story that highlights how misery had been elevated to richness and brilliance.

Is Sicily important in La Rocca's history?

In my story Sicily is the starting point of the film: I used the traditional imagining of the "Pupi" (the puppets) and a surreal dialog between the narrator Cuticchio and them, that are a cultural expression of popular theater in Sicily at the end of 1700’s and all the 1800’s.

Sicily is fundamental for La Rocca’s character because he was in a very well defined social group in New Orleans: the Sicilians were very different from other immigrants. They were not racists, and were accustomed to blacks due to Arab domination back in Sicily. Many in the cotton plantations considered Sicilians the missing link between whites and blacks, and the probably spoke a very similar language, the Mediterranean language. The history of La Rocca is different: he was not a particularly tolerant or open-minded man, even if - according to me - he had unconsciously in him this type of cultural background.

And then there is the music, a very clear contributing component: La Rocca’s father was a trumpeter in the Italian Army corps under General La Marmora, and of course in the band of his small town of Salaparuta, and clearly the primary influence of Nick La Rocca was his father Girolamo.

The musical heritage brought in New Orleans and in the United States by the Sicilians - folk and popular bands, opera - is certainly part of the wealth that enriched jazz music.

New Orleans: tell us something about the Italian emigration in this fantastic city

We could talk for hours about the stories of the Italians and the Sicilians in New Orleans at the beginning of last century!

For example, there was Anthony Sbarbaro, who later took the name of Tony Spargo, the drummer of La Rocca’s band. We know little about his origins: but in the second part of his life he was part of more than one important music bands. Then there was Louis Prima, who grew as a musician with African Americans, always played with them and never ever denied their influence in his music.

We have said that at the turn of the century there were 30,000 Sicilians out of a population of about 200,000 people in New Orleans, so it was a huge "minority": they lived in what was then called "Little Palermo", and today is the French Quarter.

There were the docks, where the Sicilians used to work unloading the ships: let's not forget that New Orleans was the main port in the southern States, the Mississippi river flowed to Saint Louis carrying goods and fruits that were traveling to the United States by ship. For example, at the beginning of 1900’s the banana trade started. There were two Italian families who controlled the traffic of bananas from Central America, the Matranga Family and Provenzano Family. In this and other types of trade the Italians excelled, making money for 20/30 years after their arrival, and this made the white Americans who lived in New Orleans very angry. They were so angry towards the Sicilians that, in 1891, 11 of them were lynched within the prison of New Orleans because they were accused of having killed David Hennessy, then chief of police. Following this lynching Italy withdrew its consuls from the United States and it seemed that even a war between Italy and the United States would be possible: at that time, Italy had a much greater naval power than the United States, and as a result of this threat the United States began to build up their own fleet!

In the autobiography of Louis Armstrong there are important references to Nick La Rocca…

Yes, in 1936 Louis Armstrong wrote his first autobiography where 2 or 3 pages were dedicated to la Rocca's influence on his music: "Livery Stable Blues" was given to those who were buying the Victrola, one of the first gramophones, which had a huge success all over the United States. Louis Armstrong had a Victrola and, together with opera records, he also had La Rocca's, which was very important for his musical education. Bix Beiderbecke, another famous white musician, fled home when he was 16 to go to New York where La Rocca was playing at that time, in 1922 or 1923.

La Rocca was a legend for all these musicians because he was the first to record a jazz song. His record had a capillary diffusion, and this is why Louis Armstrong always recognized La Rocca’s contribution to the origins of jazz.

In those times, the best seller was Enrico Caruso: however, he had never been able to reach one million copies for one of his records. The first record to ever break this goal was the Original Dixieland Jazz Band's one, which sold approximately one and a half million copies in 1917 alone.

For someone like me who loves music but is not an expert: why was the recording of Nick La Rocca in 1917 crucial for jazz music?

Precisely… because it was recorded, and because it was in Victor Studios and not in another one!

For example, one of the problems at the time was the drums: it was an element that was introduced entered in popular music by jazz, the first musical style to use it. However, the drums were difficult to record, because they had quite a bit higher tone than the other instruments. Therefore, in the recording studios, it was all a question of distance: there weren't several microphones, there was only one recording point with two cones, and then the technician had to be very good to arrange the musicians at the right distance, making very difficult the recording of the song. The fact that La Rocca and the Original Dixieland Jass Band recorded in this brand new Victor studio, which was just inaugurated, ensured that the quality is still listenable and enjoyable even today, unlike other records.

La Rocca’s band had already recorded about a month before with Columbia Records, which however had not considered the recording sufficiently attractive to place it on the market: but they didn’t have an adequate technique for recording. Today this seems a weird issue, but back then the recording technique was fundamental: if recorded with the proper one, then actually music would have a broader diffusion.

Moreover, the Original Dixieland Jass Band became famous also because it was one of the first bands to be very well marketed, using both television and radio, bringing them to embody the generation of those who left the United States to fight The First World War. While they were deploying, in 1917, that was the soundtrack; when they came back, in 1919, the same band played at the dance of the armistice in London. La Rocca and his band were the right people in the right place at the right time!

What is the relationship between Italy – and Sicily - and Nick La Rocca, nowadays?

Unfortunately, according to me, there is very little. There is a territory of Sicily, which is the Belice triangle, from which Leon Roccolo (an incredible clarinetist), Louis Prima and Nick La Rocca came from, as well as other important musicians of the era.

This territory, which was destroyed by the 1968 earthquake, has beauties that remained intact: but the tragedy is still alive. It really could become the new home for the Italian jazz, which for now is Perugia with its wonderful Umbria Jazz festival. Italy has a great jazz tradition, Renzo Arbore has immense merits in giving back a dignity to the chromosome of the Italian jazz; but to me, Italy should try to work on Belice, to bring international tourism in Sicily and to organize an important jazz festival this area.

For example, in Salaparuta there is the "Centro Studi Nick La Rocca": they were all very open and available to us, and helped us a lot during filming. Unfortunately, this institution is currently in a state of semi abandonment, local funding are just not enough. I'd hope that the Italian Ministry for Cultural Affairs would step in and take interest in it, to implement a cultural developmental project in the territory.

Nel febbraio di quest'anno cade il centenario dell'incisione di "Livery Stable Blues", il primo disco di jazz mai registrato nella storia della musica. Fu un italiano, James Dominick "Nick" La Rocca, ad avere questo primato.

Per celebrare questo controverso artista, del quale già il grande Renzo Abore ci aveva raccontato quando lo incontrammo, parliamo con Michele Cinque, giovane talentuoso regista e autore di uno splendido film/documentario che racconta questa storia, e con essa anche il rapporto tra Sicilia, musica jazz, New Orleans e l'emigrazione degli italiani (soprattutto dei siciliani) in Louisiana.

Michele, tu sei l’autore di un piccolo capolavoro: “Sicily Jass”. E’ la storia di Nick La Rocca, il siciliano emigrato a New Orleans che cento anni fa registrò il primo disco di jazz di sempre. Parlaci di "Sicily Jass"

L’idea mi è venuta mentre stavo girando un film biografico sulla vita di Louis Armstrong, il musicista jazz nero di riferimento più famoso. Leggendo la sua prima autobiografia mi sono imbattuto in Nick La Rocca.

Intervistando poi grandi critici del jazz negli Stati Uniti, come ad esempio Dan Morgenstern, ho capito l’importanza di questo cromosoma siciliano nel jazz: non c’è solo Nick La Rocca, ci sono Louis Prima, Leon Roppolo, e tutta una generazione di musicisti che a cavallo dei due secoli contribuisce a questo gene italiano e siciliano che è presente nella musica jazz.

Per quanto riguarda il film, ci ho lavorato 3 anni. E' un film documentario di 73 minuti e racconta, in parte anche in una forma intima, la vita di Nick La Rocca.

Ho deciso di utilizzare un’intervista finora mai pubblicata che La Rocca rilasciò negli anni ’50, che è anche uno dei motivi per cui La Rocca viene poi dimenticato nella storia della musica: ci sono dichiarazioni molto critiche. Dal mio punto di vista, diciamo che sul finire della sua vita La Rocca ebbe una deriva quasi psicotica, rispetto al personaggio che avevo imparato a conoscere studiandolo: credeva che tutti i meriti che aveva raggiunto, tutto quello che aveva contribuito a creare nel jazz, gli fossero stati tolti e riconosciuti agli afroamericani, per cui se la prese con loro. Essendo quello il periodo delle lotte e della rivendicazione per i diritti civili, queste dichiarazioni lo resero un personaggio “scomodo”, molto malvisto in quelli che erano gli ambienti della critica.

Io ho cercato di avvicinarmi il più possibile all’umanità di questo personaggio. Il film viaggia su due binari. Il primo è quello della finzione, grazie a un narratore d’eccezione come Mimmo Cuticchio, che guida lo spettatore al recupero della memoria storica di questa vicenda, accompagnato da Roy Paci alla tromba, da Salvatore Bonafede al piano e dalla banda di Salemi. La musica per me è un elemento narrativo, non è solo una colonna sonora.

Il secondo binario del film è quello del documentario, l’immensa indagine storica che ho compiuto negli Stati Uniti a partire da New Orleans e dagli archivi di Washington.

E’ quindi un film “ibrido”, avendo una forma sia di finzione che documentaristica, la cui struttura è stata pensata proprio per cercare di raccontare una storia molto difficile, essendo il protagonista un personaggio scomparso da oltre mezzo secolo.

In questo momento il film, che è stato finito un anno e mezzo fa, sta ancora girando i festival internazionali: è stato presentato a Rio De Janeiro e al New Orleans Film Festival, a Febbraio verrà presentato in Canada al Victoria Film Festival, in Aprile sarò negli Stati Uniti … al momento sta facendo un tour internazionale nei festival, per cui non è ancora in distribuzione, ma stiamo iniziando a pensare di produrne il DVD e di venderlo attraverso il sito del film.

Chi era Nick La Rocca, e come è accaduto che fosse lui il primo a registrare un disco di jazz?

La Rocca nasce a New Orleans nel 1896, ed è il figlio del calzolaio di Salaparuta, un piccolo paesino in provincia di Trapani. Il padre Girolamo La Rocca e la madre Vita si trasferirono nel 1880 circa a New Orleans: erano 2 dei 30.000 siciliani che abitavano a New Orleans all’inizio del secolo.

La comunità siciliana era a contatto con tutti gli strati più poveri della popolazione di New Orleans. C'era una forte influenza tra siciliani, creoli e afroamericani: questo non è tanto vero per la vita di La Rocca, ma molto più per altri personaggi che hanno fatto la storia della del jazz italiano, in questo caso siciliano, a New Orleans. La Rocca è un personaggio scomodo: è forse il primo band leader di successo, infatti uno dei personaggi del film definisce la Original Dixieland Jass Band, la sua band, i Beatles degli anni ’10, l'era del jazz.

La Rocca ha un successo clamoroso: nel 1917 si trova a New York in uno degli studi più nuovi e importanti della Victor, a incidere il primo disco della storia del jazz.

La storia è un po’ rocambolesca: lui e il suo amico e socio Eddie Edwards erano due elettricisti che suonavano per hobby: come tutti i musicisti dell’epoca a New Orleans avevano un altro lavoro. Poi però vengono invitati a Chicago nel 1916 a suonare in un locale di gangster, lo Shiller Cafè. La loro performance fa molto scalpore e un agente, Max Hart, li nota e li porta a New York, dove si esibiscono al Reisenweber a Columbus Circle, uno dei locali più famosi dell’epoca: hanno un tale successo che un impresario della Victor li porta in studio e due mesi dopo incidono, diventando la band più pagata degli Stati Uniti e vendendo 1 milione e mezzo di questo disco nel 1917.

Nel 1919 vengono invitati a suonare per il ballo dell’armistizio in Inghilterra, facendo così una delle prime tournèe in Europa mai fatta da una band americana.

Io sono convinto che in quegli anni, il fatto che la Original Dixieland Jass Band fosse una band di bianchi sicuramente ebbe un peso importante sul loro successo rispetto ad altri musicisti afroamericani che erano comunque famosi all’epoca a New Orleans, come Buddy Bolden, Kid Ory, Bunk Johnson. La Rocca sostiene di no, e questa è stata una delle grandi problematiche che lo resero poi inviso e dimenticato.

Secondo me omettere questa parte nella storia di La Rocca è un peccato, si perde l’umanità del personaggio: il figlio del calzolaio di Salaparuta, che non aveva gli strumenti culturali per difendersi negli anni ’50 nei confronti dei critici del jazz che avevano frequentato le migliori università americane. Io ho voluto rappresentare un uomo che aveva un’istruzione povera, che era stato formato dalla vita di strada, che aveva imparato a suonare “a orecchio”, con il padre che gli rompeva la cornetta perché non voleva che lui suonasse perché i musicisti erano tutti dei pezzenti. E' una storia italiana che mette in luce come la miseria sia stata elevata a ricchezza e genialità.

E’ importante la Sicilia, nella sua storia?

Nel mio racconto la Sicilia è il punto di partenza del film: ho utilizzato la tradizione immaginando un dialogo surreale tra il narratore Cuticchio e i suoi Pupi, che sono l’espressione culturale del teatro popolare della Sicilia della fine del ‘700 e di tutto l’800.

Nella storia di La Rocca, la Sicilia è fondamentale perché lui si trova in un gruppo sociale molto ben definito a New Orleans: i siciliani erano molto diversi dagli altri immigrati. Non erano razzisti, erano abituati ai neri avendo avuto dominazioni arabe: erano addirittura considerati l’anello mancante tra bianchi e neri nelle piantagioni di cotone, e probabilmente parlavano anche una lingua più simile, la lingua del mediterraneo. La storia di La Rocca non racconta questo: non era un uomo particolarmente tollerante o aperto, però, secondo me, lui aveva comunque inconsapevolmente interiorizzato questo tipo di background culturale.

E poi c'è la musica, una componente molto chiara: il padre di La Rocca era un trombettista nei bersaglieri del generale La Marmora, oltre che nella banda del paese, e chiaramente l’influenza primaria di Nick La Rocca è stato il padre Girolamo.

Questo patrimonio musicale che i siciliani hanno portato con loro – le bande popolari, l’opera - a New Orleans e negli Stati Uniti, è sicuramente parte della ricchezza che poi va a confluire nel jazz.

New Orleans: ci dici qualcosa sull’ emigrazione italiana in questa fantastica città?

Si potrebbe parlare per ore delle storie degli italiani e dei siciliani a New Orleans all’inizio del secolo!

Ad esempio c’era Anthony Sbarbaro, che prese poi il nome di Tony Spargo, che era il batterista della band di La Rocca. Di lui si sa poco, soprattutto delle sue origini: si conosce meglio la seconda parte della sua vita perché farà parte di importanti band. E c'era Louis Prima, che crebbe con gli afroamericani, suonò da sempre con loro e non negò mai questa influenza nella sua musica, anzi.

Abbiamo detto che a New Orleans c’erano 30.000 siciliani a cavallo del secolo su una popolazione di circa 200.000 persone, quindi era una “minoranza” enorme: l’odierno quartiere francese veniva allora chiamato “Little Palermo”.

C’erano i Docks, dove lavoravano i braccianti che scaricavano le navi: non dimentichiamoci che New Orleans è il porto principale degli Stati del sud, il Mississippi arrivava a Saint Louis, le merci e la frutta viaggiavano per tutti gli Stati Uniti via nave. Ad esempio, all’inizio del ‘900 inizia il commercio delle banane. C’erano due famiglie italiane che controllavano il traffico delle banane dal Centro America, i Matranga e i Provenzano: questo e altri tipi di commercio nei quali gli italiani si distinguevano, facendo fortuna dopo circa 20/30 anni dal loro arrivo, fecero molto arrabbiare gli americani bianchi che abitavano a New Orleans, tant’è che nel 1891 11 siciliani vennero linciati all’interno del carcere di New Orleans poiché erano stati accusati di aver ucciso David Hennessy, allora capo della polizia. In seguito a questo linciaggio l’Italia ritirò i propri consoli dagli Stati Uniti e si paventò una guerra tra l’Italia e gli Stati Uniti: l’Italia aveva una potenza navale molto maggiore rispetto agli Stati Uniti a quell'epoca, e quindi gli Stati Uniti iniziarono a mettere su la loro flotta proprio in seguito a questa minaccia!

Nell’autobiografia di Louis Armstrong ci sono importanti riferimenti a Nick La Rocca…

Si, nel 1936 Louis Armstrong scrive la sua prima autobiografia nella quale c’è una parte di 2 o 3 pagine dedicata proprio all’influenza che aveva avuto la Original Dixieland Jass Band sulla sua musica: "Livery Stable Blues" veniva dato all’epoca con il Victrola, uno tra i primi grammofoni lettori di dischi, che ebbe una distribuzione a macchia d’olio nelle case degli Stati Uniti. Louis Armstrong ne aveva uno, e, insieme ai dischi operistici aveva dunque questo disco, che fu per lui molto rappresentativo. Bix Beiderbecke, che era un altro musicista famosissimo, bianco, scrisse addirittura a La Rocca, e scappò di casa a 16 anni per andare a New York dove La Rocca stava suonando a quell’epoca, nel ’22 o ’23.

La Rocca era un mito per tutti questi musicisti perché è stato il primo a incidere. Il suo disco ha avuto una diffusione capillare, per cui Louis Armstrong ha sempre riconosciuto l'apporto che La Rocca diede al jazz delle origini.

A quei tempi il best seller era Enrico Caruso: le sue vendite, però, non avevano mai raggiunto il milione di copie, mentre il primo disco a sfondare questa soglia fu quello della Original Dixieland Jass Band, arrivando a vendere circa un milione e mezzo di copie nel solo 1917.

Per chi come me ama la musica ma non è un esperto musicale: perché la registrazione di Nick la Rocca nel 1917 è stata fondamentale per la musica jazz da lì in poi?

Lo è stata proprio perché è stata registrata, e perché lo fu con la Victor e non con un’altra casa.

Uno dei problemi, all’epoca, era, per esempio, la batteria: era un elemento che entrò nella musica popolare con il jazz, il primo stile musicale ad usarla. Però la batteria era difficilissima da registrare, perché aveva un tono molto più alto degli altri strumenti, e quindi nella registrazione era tutta una questione di distanza: non c’erano vari microfoni, c’era un solo punto di registrazione con due coni, e quindi il tecnico doveva essere bravo a sistemare i musicisti alla giusta distanza, rendendo l'incisione del pezzo molto difficile. Il fatto che La Rocca e la Original Dixieland Jass Band incisero in questo nuovissimo studio della Victor, appena inaugurato, fa sì che la qualità sia ancora oggi ascoltabile e godibile a differenza di altri dischi.

La band di La Rocca aveva inciso circa un mese prima per la Columbia, che però non aveva reputato l’incisione sufficientemente interessante da metterla sul mercato, anche perché non aveva una tecnica adeguata. Oggi sembra strano un simile discorso, ma all’epoca la tecnica era uno spartiacque: se registravi con quelli bravi effettivamente poi la musica aveva una diffusione diversa.

Inoltre, l’Original Dixieland Jass Band divenne famosissima anche perché fu una delle prime band sulla quale fu fatto un grande lavoro di marketing, utilizzando mezzi televisivi e radiofonici, portandola ad incarnare la generazione di coloro che dagli Stati Uniti andavano a combattere la prima guerra mondiale. Mentre partivano, nel 1917, quella era la colonna sonora; al loro rientro, nel 1919, la stessa band suonò al ballo dell’armistizio a Londra. La Rocca e la sua band furono le persone giuste, al posto giusto nel momento giusto!

Che rapporto c’è tra l’Italia di oggi, e ancora di più la Sicilia di oggi, e Nick La Rocca?

Purtroppo, secondo me, si fa molto poco. C’è un territorio della Sicilia, che è il triangolo del Belice, dal quale ebbero origine Leon Roccolo (un clarinettista incredibile), Louis Prima, Nick La Rocca e le loro famiglie, oltre che altri importanti musicisti di quell’epoca.

Quel territorio, distrutto dal terremoto del 1968, conserva delle bellezze che sono rimaste intatte, ma la tragedia è ancora viva. Potrebbe davvero diventare il nuovo territorio del jazz in Italia, che per ora è Perugia con l’Umbria Jazz, dove è stato fatto un lavoro meraviglioso. L’Italia ha una grandissima tradizione jazzistica, lo stesso Renzo Arbore ha dei meriti immensi nell’aver restituito una dignità al cromosoma italiano del jazz: però secondo me bisognerebbe cercare di lavorare anche su quel territorio, di portare il turismo internazionale lì, di organizzare un festival di jazz di livello europeo in quelle zone.

Per esempio a Salaparuta c’è il centro studi Nick La Rocca: tutti sono stati molto aperti e disponibili con noi, ci hanno aiutato molto durante le riprese. Purtroppo, però, il centro attualmente è in uno stato di semi abbandono: le forze locali non ce la fanno, ci vorrebbe un interesse da parte del Ministero dei Beni Culturali per fare un lavoro di sviluppo culturale sul territorio.