John Battersby Campitelli (President of Italiadoption)

Una storia di amore, genealogia e famiglia, tra l'Italia e gli Stati Uniti

At the end of World War II, Italy was a country in great difficulty. Relieved by leaving behind a terrible period, but with a difficult reconstruction in front of them, the Italians counted many situations of poverty and great discomfort. In this historical and cultural context, a forgotten page of Italian history reemerges, a page in which the United States, also through the commitment of ordinary citizens, not only gave material and economic assistance, but decided to welcome into their families thousands of children who had been left in the orphanages and institutes scattered throughout Italy. Through two agencies appointed and authorized by the Italian government to facilitate international adoptions, these "orphans" emigrated to a new continent and a new life.

In recent times, this delicate issue has returned to the attention of the mass media because many of them now intend to reclaim their origins, by asking for access to the identity of their biological parents and by recognition of their dual Italian and American citizenship. We talk about it with John Battersby Campitelli, one of the pioneers of this difficult journey back in time.

John, an article written by Silvia Cassamagnaghi, titled "The adoption of Italian children in the United States. The work of the Catholic Relief Service and the Catholic Committee for Refugees" has recently been published. Can you please describe us this topic?

Italy is today one of the first countries in the world to receive children through international adoptions, but few people remember that a few decades ago it was one of the countries with the largest number in the world of emigrations for adoption. What were the dynamics, and where did these "orphans" of the Italian diaspora end up? This is the main theme developed by FrancoAngeli in the magazine "Italia Contemporanea" and written by the researcher Silvia Cassamagnaghi of the University of Milan, with whom I have been collaborating for some time.

One of the two international bodies that proved most actively involved in international adoptions from Italy was the Catholic Committee for Refugees (CCR) of the National Catholic Welfare Conference (NCWC), which was entrusted with the protection of Catholic children emigrated from Italy. The other body in charge was the International Social Service of the Italian Red Cross (CRI), but with much smaller numbers.

The massive campaign for adoptions, carried out in the twenty years from 1950 to 1970 by the American Catholic community, created in fact a huge demand for European children. Italy (in addition to Ireland, which was in second place) became the ideal pool of supply, due to its particular economic, social and religious characteristics, and the "flexibility" shown by its government, convinced that the path of international adoptions was an excellent solution so that these young children could not experience misery.

You've done extensive and in depth research: which numbers are we talking about? And what geographic areas are affected by this topic, both in Italy and in the United States?

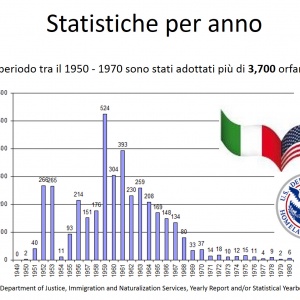

According to the Immigration and Naturalization Service statistics, and by carefully analyzing the passenger lists published in the American archives (readable online), and thanks to the work carried out by the JRC and the SSI, we know that between 1950 and 1970 more than 3,700 Italian children were welcomed by American families, mostly of Italian American origin. This created a sort of unprecedented "migratory chain", since - in the application forms - aspiring parents often expressly indicated that they wanted only young children from the Italian peninsula.

From the data we processed, and of which we have requested official confirmation from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Rome (which was in charge to give permission to the expatriation and the authorization to the Police Headquarters of Rome for the issuance of the passport to the minor), it appears that the greatest concentration of the places of departure in Italy were the large urban cities (Turin, Milan, Venice, Florence, Florence, Rome, Naples and Palermo), that had suitable facilities to accommodate pregnant mothers and were large enough to hide any "uncomfortable" pregnancies.

As far as the destination in the United States is concerned, we requested precise data to the Italian Embassy in Washington DC, which was responsible for the legal protection of the "orphans" during the whole phase of integration into American families, but we are still waiting for an answer. However, from the analysis of the data we have today, we already have evidence that the most affected States by the diaspora are New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and California.

John, you are one of the living witnesses of this incredible experience. Please, tell us your story

Already from my name, John Pierre Campitelli, you can understand that I am half Italian and half American! As a professional, I am an IT engineer, I have been working for over twenty years in an American multinational company with offices in Italy, and as such I often find myself crossing the ocean to deal with the marketing and renewal of corporate communication and collaboration tools.

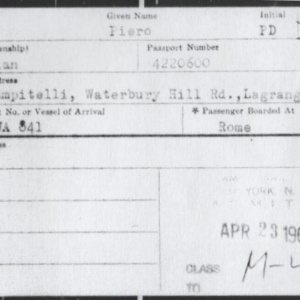

I feel myself a real protagonist and direct interested in this incredible experience because I was born in Italy in 1963 to "unknown" parents. A few days later I was handed over from my first mother (or biological mother) to the Provincial Institute for Childhood in Turin. I remained there almost two years until April 1965, when I emigrated to the United States to be adopted by my Italian American parents (my paternal grandfather had in fact emigrated to the United States in 1910, for other reasons).

Only in 1991, after four years of assiduous research, I finally managed to find the woman who gave me my life using anonymous childbirth, a common situation for the other real protagonists of this affair, the women who left - many of them despite themselves - their children in the hands of Italian institutions, and who until now have not been represented except through an intermediary.

We should also listen to the voices of women like my mother Francesca, who suffered the torment of having to irreparably separate themselves from their children who had been carried in their womb for nine months, aware that the bigot mentality of the time would not allow them to grow them as calmly as they would have liked. We should also not forget those biological fathers who had a role in our conception.

For us children, too, there has been the trauma of abandonment, a primary wound that is difficult to heal, because it remains an indelible mark in our essence that is difficult to understand for those who have not personally lived it.

On this specific topic, you have created an association called Italiadoption…

The rediscovery of my origins was for me an unforgettable and decisive moment in the decision to sublimate a pain and turn it into something positive. For this reason I committed myself to set up an association of mutual help for adoptive children and biological parents who express the desire to recompose their past and find themselves: this is how in 1989 I founded the Italiadoption association in the United States.

Through the commitment of more than 300 members scattered throughout the United States, and in close collaboration with the Italian Association of Adopting Children and Natural Parents (F. A. e G. N.), Italiadoption has three main goals. We aim to find the more than 3,700 "orphans" of the Italian diaspora; to maintain a register of personal data that can be consulted online linked to a database of DNA profiles (#DNAdozione) in order to facilitate and verify the discovery of their relatives through the use of genetic genealogy; and to document the stories of each of them and share them on social media.

Two are the results we want to achieve: the right to our origins (#dirittoalleorigini) without discrimination of any kind, and the recognition of double Italian and American citizenship for all children of the diaspora without bureaucratic delays.

These stories are intertwined with the theme of Italian citizenship, with the dual reference to both the recovery of it by those who lost it, and the Italian debate on Jus Soli. What lessons can be learned from your experiences on this topic?

Precisely because today's Italian law on citizenship provides for Jus Soli, the right to citizenship acquired by birth on Italian soil for those born of "unknown" parents (in fact, the full act of birth have to bears the words "woman who does not allow to be named"), the majority of the children of the Italian diaspora in the United States are actually Italian citizens, because they were naturalized American citizens when they were still minors.

It is a pity, however, that not everyone is aware of the problems inherent in the procedures for enrolment with A.I.R.E. (the Registry of Italians Resident Abroad) because of the effects of foreign adoption, which was often not transcribed on the margins of birth certificates in the municipalities of origin, causing a discrepancy in personal details. There have been many cases of Italian children adopted in America who have been denied the issue of passports because in Italy they were still registered with the old name given by the registry office before adoption. Not to mention the fact that women in the United States change their surname with the marriage, which is problematic for the registration in Italy. Me myself I have seen my name entered in the register of wanted persons, because Italy considered me a draft dodger!

Unfortunately, over the years, we have encountered considerable problems in exercising our right to our origins and to dual citizenship, precisely because of the lack of knowledge of this subject and because there is not yet a uniformity of procedures in the various Italian consular districts in the United States.

As a personal experience, I would like to conclude by recalling that it has already been difficult for me to leave my country of origin to go and live in a new culture and learn a new language and to have to deal with different habits and customs. For this reason, whatever we can do to facilitate the integration of our children even at school can only increase their self-esteem and make them feel equal to their peers.

In conclusion, what can we tell our Italian American readers about this little-known page in the history of the relations between our two countries?

The appeal that I would like to make to all the Italian Americans who follow We the Italians is to tell us if they are aware of people involved in this situation, so that we can get in touch with each other and then help us to recognize our right to dual citizenship and to access our origins.

You may be interested

-

“The Art of Bulgari: La Dolce Vita & Beyond,...

by Matthew Breen Fashion fans will be in for a treat this fall when the Fine Arts Museums...

-

“The Hill” St. Louis’ Little Italy

When the fire hydrants begin to look like Italian flags with green, red and white stripes,...

-

13th Annual Galbani Italian Feast of San Gen...

In September of 2002, some of Los Angeles' most prominent Italian American citizens got to...

-

1st Annual Little Italy Cannoli Tournament

Little Italy San Jose will be hosting a single elimination Cannoli tournament to coincide...

-

30th Annual Art Holiday Walk, Winter Winter...

Holiday walk hours Friday, 12/5 noon-9pm, Saturday ,12/6 noon-9pm Sunday, 12/7 noon-6pm. S...

-

A wreath for Columbus and three crowns for t...

The Columbus Day Committee of Atlantic City along with the Bonnie Blue Foundation annually...

-

An Unlikely Union: The love-hate story of Ne...

Award-winning author and Brooklynite Paul Moses is back with a historic yet dazzling sto...

-

Candice Guardino Brings GILDA AND MARGARETTE...

Candice Guardino is adding to her list of successful theatrical productions with the debut...