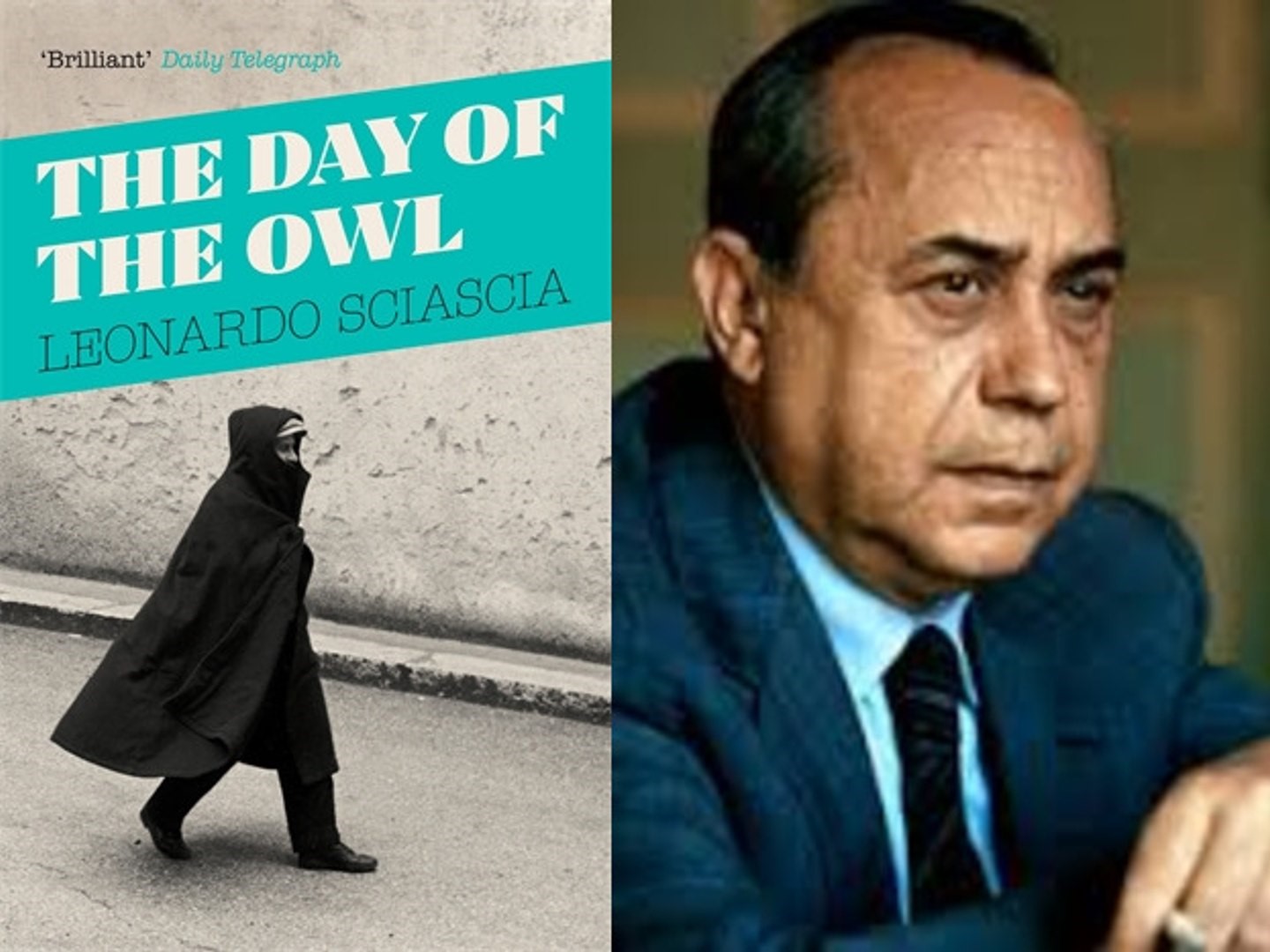

The Day of the Owl (Il giorno della Civetta) is a novel written by Leonardo Sciascia and published in 1961. Throughout his life, the author (1921-1989) wrote about a wide variety of topics.

He first studied the historic and social origins of the underdevelopment in Sicily, drawing inspiration from his experience as an elementary school teacher. Then, he gained increasing success with a series of short novels – among them there was also The Day of the Owl – taking place in Sicily.

Finally, he focused on historiography research to deal with the issue of terrorism – more specifically, the case of the kidnapping and killing of Aldo Moro - to the point that he was appointed minority rapporteur in the parliamentary committee of inquiry into the assassination of Aldo Moro and terrorism in Italy. In fact, he had been elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1979 with the Radical Party.

The story of this book revolves around the killing of Salvatore Colasberna, an entrepreneur in a small town in Sicily, who is shot while running to catch the bus in the square of the town, which opens up an investigation led by the Captain of the Carabinieri Bellodi, who had arrived in Sicily from Parma, is new to the job and is characterized by a strong sense of justice.

Immediately thereafter, he is sure that the murder was a matter concerning the mafia and public contracts. No one is willing to talk. He pursues his probe anyway, and he is finally able to get people to talk and find out what happened and how the facts unfolded, despite the homicide of a witness and a Carabinieri’s informant.

In the end, Bellodi gets to the bottom of the matter, exposing the hit men and getting a confession from one of them, and the instigator, the local mafia boss Mariano Arena.

In the meantime, some people belonging to the political environments in Rome start to get worried that Bellodi’s investigation might expose someone close to the government and uncover their involvement in the crime. Therefore, such people ultimately decide to produce false evidence to exonerate the criminals and wrongfully lead the inquiry to consider the case as a crime of passion.

Captain Bellodi is back in Parma on leave, and he finds out from the papers that the case he has built and presented following his investigation has been dismantled and that everyone involved has been exonerated. He then decides to go back to Sicily to fight for the truth.

“This short, beautifully paced novel is a mesmerizing description of the Mafia at work.”

In 1968, the book became a movie with Claudia Cardinale and Franco Nero and in 2023 such movie was shown as an event at the MoMa museum in New York. It was presented with the following description of the story, “Leonardo Scascia made fascism and organized crime the focus of his existential crime novels. The Day of the Owl is one of his most celebrated, set in a provincial Sicilian town where the events leading to a man’s seemingly accidental death become enshrouded in a mysterious, menacing silence, leading fledgling detective Captain Bellodi to suspect a Mafia hit job.”

This book has been considered as the first and greatest novel talking about the mafia.

Sciascia recalls that at the time of writing there had been done certain studies on the subject and there was also work done by another Sicilian author, but no one had ever dealt with the matter on this scale and in a great narrative project. The word mafia wasn’t even pronounced loudly.

This book is considered as the one that most represents its author, his style, and his way of investigating and narrating a story.

The author himself used these words to describe the work he has done around this book, “it even took me a year, from one summer to the next, to make this tale shorter. But the result at which this work of mine of "hollowing out" wanted to reach was aimed more at parrying the possible and possible intolerances of those who might consider themselves, more or less directly, affected by my representation, rather than at giving measure, essentiality and rhythm, to the tale. Because in Italy, you know, you cannot joke with either saints or jacks: and let alone if, instead of joking, you want to get serious.”