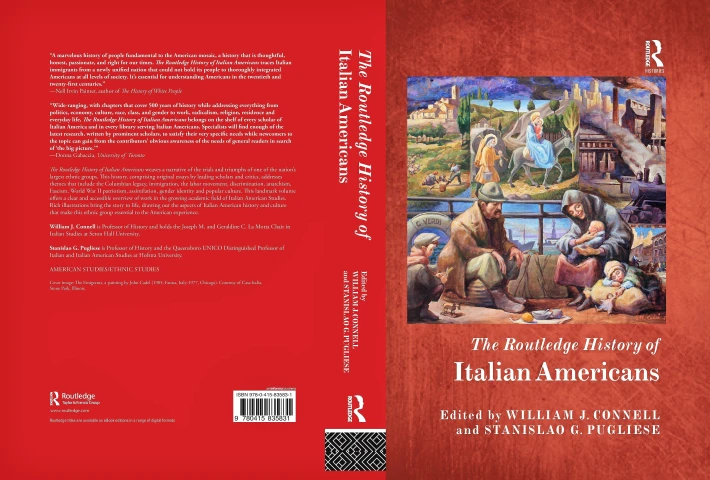

There are several books that tell in many ways one or more aspects of the Italian American community; and there are some that have been entrusted with the mission of telling it in its entirety. Some of these works are excellent, but in these days a book is coming out that promises to give a never seen before picture of the Italian American experience.

It is a monumental work, created by two scholars who have been working on these themes for years, Bill Connell and Stan Pugliese. We welcome them on We the Italians, and we thank them very much for their work, that will be available here from October 3rd.

Bill, Stan, you are publishing a book of 660 pages, all about the Italian Americans and their history. I must confess it isn't easy to formulate just a few questions … you and the several authors of the book cover pretty much the whole nine yards. It's simply AMAZING. You two have done such a tremendous job, this will be an encyclopedia that will make history within the Italian American community

Stan: Well, we hope so.

Bill: Stan said some of this in his conclusion to our book: it’s like giving a history to a people, which is a very special thing. It’s not like writing the history of a war, or an election, or writing a biography, you know. Writing the history of a “people” is what Moses did, or when, after the fall of the Roman Empire, they began writing histories of the Goths, of the Vandals, of the Lombards.

Like those, this is the history of a migratory people. And it has never been done in a critical way, so as with those histories have been lots of legends, legends of origin, for instance, and these things have to be looked at critically. There was an Italian, Polydore Virgil, who wrote the first solid “ History of England,” in which he demolished legends about Britain being settled by a Roman called “Brutus.” When his book was published it upset some people who believed in these traditions so much that they accused him of burning ancient manuscripts. Like Polydore, we’re trying to offer a history based on the real lives of Italian Americans, as opposed to popular legends.

When and how did you have the idea of this encyclopedia?

Bill: I always thought there was a need, for Italian Americans of a detailed multi-authored history. Italian scholarship has created some superb multi-authored histories - the Einaudi “Storia d’Italia”, and the one produced by UTET, come to mind. The goal is to bring together authors who have different expertise and different points of view to cover a whole historical landscape. Italian Americans didn’t have that.

When UNICO National, a major Italian American charitable organization that has sponsored a number of endowed chair and institutes for Italian Studies in American universities, asked what could be done to crown their efforts, I suggested doing a book like this that would include contributions from the relevant experts. I assumed someone else would then edit it, but when they asked me to do it, I reached out to Stan, first as a friend, but also because Stan has done detailed work on later periods of this history, while I have done a lot on earlier periods, so together we made a really good team.

Stan: I think it was tremendously ambitious, but also necessary. In every class that I teach, I ask students to do hypothetical exercises, such as: “Imagine if you wake up tomorrow and you’ve forgotten everything about yourself: your name, your family, your ethnicity, your religion. Would you be the same person that you were a couple of days ago?” And they realize that no, they would not be the same person.

Then I try to get them to extrapolate from that. So, what if a whole civilization or ethnic group forgot its history, what would be the consequences of something like that? I don’t think Italian Americans were in danger of losing our history, I think we were in danger of not remembering our history with all its nuances, with all its complexity. I think the Italian American community now, after more than 100 years from its first arrival, is politically, economically, psychologically, socially in a place from where we can look back at our past with all its virtues and defects and put together something like this book.

Also, it is important because no single person could do something like this: it had to be a collective effort. So, we are extraordinarily grateful to the three dozen collaborators, our colleagues, friends and scholars from all over the world, who have really gone above and beyond. And Bill, who was the master at bringing all these people together and working with them, really has accomplished something extraordinary.

Is there a pattern you chose … a thematic one, or a geographic one, or maybe following a timeline?

Bill: Yes, there is a kind of pattern, definitely a chronological pattern although many of the chapters are thematic. There are four parts to the book. The first part is about exploration and foundation, the second is about coming to the United States and making “Little Italies,” the third part is about becoming Americans and the fourth part is about the more recent experiences of Italian Americans.

You put together so many authors, something that only people who have charisma and recognition by their peers would be able to do. Italians are not known for easily participating altogether for a common effort. How did you succeed in putting 37 incredibly talented Italian American and also Italian authors together, and come out with a coherent, well calibrated, thorough book?

Stan: I should say that as a testament to Bill’s organizational skills, I don’t think one scholar that we approached with an invitation turned us down. In fact, it was sort of like an embarrassment of riches, that we had to not invite, if that is the right word, several people that we would have liked to include. But it would have been almost impossible to include everybody. As it is, I think we did a very good job at covering a lot of ground, both material that is supposedly common knowledge and things that most Italian Americans and Americans might not know about. And I have to say that all of the contributors were really very gracious and very patient with our suggestions and with everything that we asked of them. It’s really wonderful that it turned out to be such a pleasant project to work on, even though it was an extraordinary amount of work.

Bill: One important thing to add - something long overdue, but it’s wonderful - is that now there is serious interest in Italy for the history of Italian Americans and the Italian diaspora. It’s a growing area of research within Italian academia. And we made a special effort to include some Italian authors, either by translating their work into English, or by recruiting Italians who write in English. So, there is an international aspect here that you don’t find in any of the earlier accounts of Italian Americans.

I agree with you, this book is important for Italy too. Is the book going to be published in Italian in Italy?

Bill: If there is a publisher in Italy who is interested, we will be happy to make whatever arrangements are necessary. Some of the chapters were originally written in Italian, which may make things a little easier. The book will be an ideal resource for Italian researchers interested in studying Italian Americans.

Bill, your introduction starts with this sentence: "It was in the 1980s that Italian Americans finally “made it” in American society." Please, explain us why

Bill: It’s important to realize the progress in social status that Italian Americans have made. In the 1880s and 1890s, the image of Italian Americans was very negative. We have chapters discussing the lynching of Italian Americans, the discrimination they faced, the cartoons that depicted Italians as ruffians and gangsters. There was a great sense of Italians as outsiders, as inferior.

The situation only began to change during World War II, when a great integration of Italian Americans to American society took place. After WWII the Italian presence in mainstream American culture continued to grow, thanks to singers like Frank Sinatra, thanks to the adoption of Italian dishes like spaghetti and pizza that became staples in the American diet in the 1950s. By 1963 or 1964 Italian Americans could reasonably anticipate that this role in the mainstream would continue to grow.

However, the late 1960s and 1970s were a very difficult time for Italian Americans. It was a period of leaving the cities, of what was known as white ethnic flight. There were tensions with other ethnic groups, with African Americans and Puerto Ricans. The image of the Mafia spread throughout American society in the 1970s.

So, there was a step backward, as many perceived it, and it was only in the 1980s that newspapers and magazines began to announce that Italian Americans had “made it,” or, as some historians have put it, they “became white.” So, that’s what it meant to me, to refer to “making it” in the 1980s. Of course, there’s a certain irony to this. One thinks, first, of those who haven’t “made it.” And then there are also the ways in which Italian Americans preserve a particular identity down to this day. Are they just “ordinary” Americans today? That is a question the authors of this book grapple with again and again.

Stan: If I just could add something to that. When I teach my course on Italian American history I often begin on the first day of class saying to my students: “If you were having a conversation 100 years ago in 1917 and said to someone ‘By the end of the 20th century there would be not one but two Italian Americans on the Supreme Court’ they would have thought you were crazy.”

Like Bill says, by the time you get to 1980s, we have Italian American governors, politicians, and Supreme Court justices later on. That is an important story in itself, but the flip side of that is there is a danger of forgetting a past. Sometimes you have to pay a price for becoming mainstream.

I cannot choose between the several papers in the book: all of them are beautifully written, very interesting, addressing a fundamental topic for the Italian American community. What's the most curious thing you learnt working on this?

Stan: I came to Italian American studies from Italian studies, so I had a certain perspective. I had always known about the incredible diversity of Italian American culture. Still, I think that this was really reinforced going through the essays: how the experience in New York was very different from New Orleans, how it was different in San Francisco, how there were communities in places like mining towns in Colorado, or share-cropping plantations in the American south, or cigar factories in Florida. And so, what I came away with was this renewed appreciation for the resiliency of Italian American culture and a question: what was it in Italian culture that made the possibility of success in Italian American culture? I think that it was especially the culture from the “Mezzogiorno”, the south of Italy, the civilization that my parents came from, that enabled them to cross thousands of miles of ocean in a couple of weeks and become successful in a completely different kind of culture. I think that if you look at the essays altogether, even though each one is a small jewel in itself, they gave this complex portrait of a sociological and historical, psychological transformation that is really extraordinary.

Bill: Where this was most revealing for me, and it opened up things that I hadn’t studied before, was in the accounts of the experience of Italian American women. For instance there was a great emphasis on the poverty and squalid living conditions of the Little Italies in early scholarship. But things were even worse for women back in Southern Italy and Sicily. When they got to Little Italy there was a more extended social world made newly available to them. It was liberating for these female immigrants that they had the ability to make money through weaving and embroidery. Women would socialize with one another in tenements in ways that they couldn’t do in their isolated homes in isolated rural villages back in Italy and Sicily. The special experience of Italian American women can be seen continuing in the chapters on memoirs, journals and novels that our authors Mary Jo Bona and JoAnne Ruvoli explore in their essays. This was particularly illuminating to me.

Stan, without spoiling your conclusion, please tell us why you named it "The Future of Our Past" …

Stan: The conclusion isn’t so much an attempt at a prognosis or prophecy of the future. Any depiction of the future of the Italian American community that we come up with would probably be wrong. What I am hoping to do in the conclusion is to get readers of the Italian American community to think of this book not as a culmination, but as the beginning of something: two or three generations of scholars working together, opening up new paths, new ways of thinking about the Italian American experience, whether it be gender, whether it be through cultural studies, whether it be through things like architecture, or politics.

That’s why I think it’s incumbent upon us to think about Italian American history in a different way. It was Benedetto Croce echoing Giambattista Vico, who said: “The only way you can really know something is by writing its history.” If we don’t write our own history, someone else will. This is more like a manifesto for Italian Americans to be more involved in the writing of our history, in the way we’re depicted in the media, textbooks, literature and the general culture.

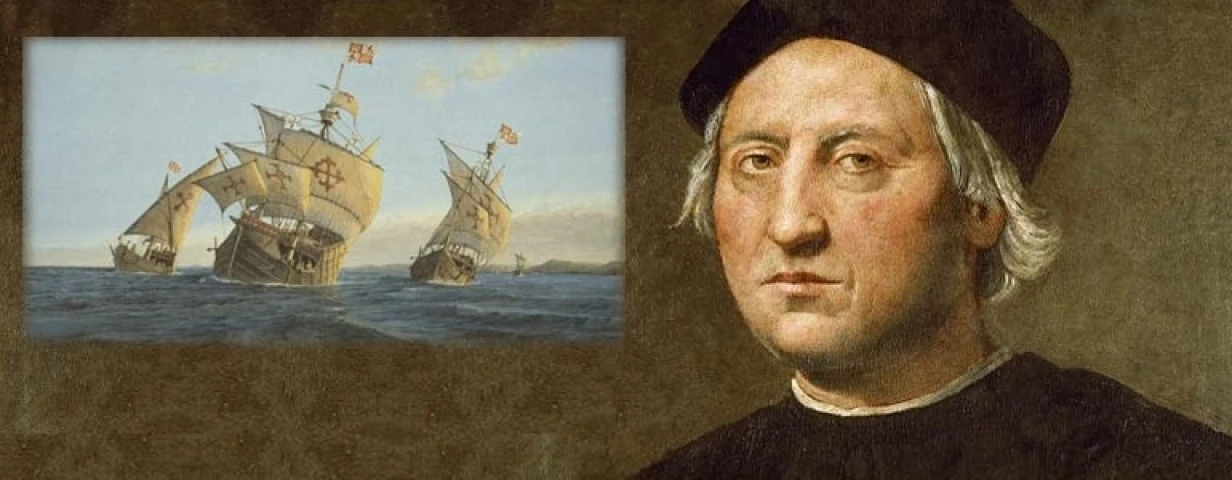

Last question: what do you think about the repeated attacks towards Christopher Columbus? What the Italian American community should do?

Bill: This history does begin in 1492. It wasn’t just that Columbus, Vespucci happened to be Italian. While it is true that the early voyages into the Atlantic sailed under the flags of Atlantic nations, what’s not been sufficiently recognized is that the funding for these expeditions came from Italian venture capitalists. So, historically speaking, the discovery of the New World was an enterprise that was more broadly “Italian” than is usually recognized. As for what happened as a consequence, with respect to the Columbus Day holiday, there needs to be a recognition that this is history, that it happened a long time ago. History obviously leaves room for regret and mourning, but that doesn’t mean that the past and its legacies should be forgotten.

Recently the organizers of the Columbus Day parade in New York City consulted me on how to handle the historical questions about Columbus. I said they really should do two things. First, come out with a very strong statement acknowledging that like many people in history Columbus did some things that even back then were morally unacceptable and still are today. In fact he did some awful things as Viceroy on the island of Hispañola in 1499 and 1500 that led to his removal, and historians in recent years have continued to discover more misdeeds in documents in the archives in Spain. But what Columbus did in 1492 effectively created the world we now live in. It was a moment as important in the history of the human race and of this planet as the discovery of agriculture. That would seem reason enough to commemorate it.

My second recommendation, if this is to remain a national holiday, was to make a strong effort to include other ethnic groups, especially Native Americans. I pointed to the 1892 parade in New York, when the emphasis was on schools and public education, which was a new thing back then, and the parade included children from all the schools, all the nationalities. There was the Dante Alighieri Italian School but also the Carlisle Indian School from Pennsylvania. So you had Italian and Native American schools marching together in the Columbus Day parade.

Stan: I would just add that I think the Italian American community is or should be at a point now where we can look back at our history with a more critical eye - not that we have to criticize everything - but to understand that things are a little more complex. So, for example, leaving aside the criticism of his behavior in the New World and slavery, just take for example this Earth changing shift, which is that Columbus’ work, his exploration, basically signaled the end of the Italian city-state dominance of European culture. They went from the city-states of Genoa and Venice and Milan and others being the center of political, cultural, economic life of Europe, to the Atlantic becoming the dominant force in the world. There is a tremendous historical irony that it was an “Italian” who was responsible for the “decline” of Italy in the modern world. So, in a way, Columbus is a microcosm of the complexity of Italian American culture. Sure, we should celebrate our accomplishments in triumph, but at the same time we have to acknowledge that those very triumphs and accomplishments sometimes are a little more complicated that we think.

And what Italy should do for you? If we should do something.

Stan: As Bill mentioned, we made an effort to include younger generations of Italians scholars who were working on Italian American studies. For way too long, Italian scholars had considered Italian American culture like a backwater, something that wasn’t even worthy of their attention, refusing to realize that there are just as many Italians outside of Italy as there are living in Italy. That’s changed, and we have the scholars in our volume to prove it. As far as Columbus is concerned, I think Italy too has to bear some kind of responsibility in demonstrating Columbus’s incredible impact on the world: I mean the modern world would not exist without him, with all the kind of moral, political and ethical complexity that he embodied.

Bill: To continue Stan’s thought, there’s a maturation process that is going on among Italian Americans. As Stan says, they’ve reached a status where they can criticize themselves and also accept criticism. Now is the time for a mature recognition of the complexity of history, both by Italian Americans and also by the Italians in Italy who are now increasingly on the receiving end of the experience of mass immigration.

Ci sono diversi libri che raccontano in molti modi uno o più aspetti della comunità italo americana; e ce ne sono alcuni che hanno come mission quella di raccontarla nella sua interezza. Alcune di queste opere sono eccellenti, ma in questi giorni uscirà un libro che promette di dare un quadro dell'esperienza italoamericana mai visto prima.

Si tratta di un'opera monumentale, realizzata da due studiosi che da anni lavorano su questi temi, Bill Connell e Stan Pugliese. Diamo loro il benvenuto su We the Italians, e li ringraziamo molto per il loro lavoro che sarà disponibile qui dal prossimo 3 ottobre.

Bill, Stan, state pubblicando un libro di 660 pagine, tutto dedicato alla storia degli italoamericani. Devo confessare che non è facile formulare solo poche domande... voi e i diversi autori del libro coprite praticamente ogni argomento. È semplicemente FANTASTICO. Avete fatto un lavoro eccezionale, sarà un'enciclopedia che farà la storia della comunità italoamericana

Stan: Beh, lo speriamo.

Bill: Nella sua conclusione, Stan ne ha parlato: è come dare una storia ad un popolo, una cosa molto speciale. Non è come scrivere la storia di una guerra, di un'elezione, o scrivere una biografia. Scrivere la storia di un "popolo" è ciò che fece Mosè, o è ciò che fu fatto quando, dopo la caduta dell'Impero Romano, iniziarono a scrivere le storie dei Goti, dei Vandali, dei Longobardi.

Come in questi casi, questa è la storia di un popolo migratorio. Questa storia non è mai stata scritta in modo critico, così come con quelle storie si sono create molte leggende, leggende sulle loro origini, per esempio: e queste cose devono essere guardate criticamente. Ci fu un italiano, Polidoro Virgili, che scrisse la prima vera "Storia dell'Inghilterra", in cui demolì le leggende secondo cui la Gran Bretagna sarebbe nata da un romano chiamato "Brutus". Quando il suo libro fu pubblicato, sconvolse alcune persone che credevano in queste tradizioni, tanto da accusarlo di aver bruciato antichi manoscritti. Come Polidoro, stiamo cercando di offrire una storia basata sulla vita reale degli italoamericani, al contrario delle leggende popolari.

Quando e come avete avuto l'idea di questa enciclopedia?

Bill: Ho sempre pensato che ci fosse bisogno per gli italoamericani di una storia articolata e scritta da più autori. La comunità di accademici italiani ha creato delle meravigliose raccolte scritte da più autori - mi viene in mente la Storia d' Italia Einaudi e quella prodotta da UTET. L'obiettivo è quello di riunire autori con competenze e punti di vista diversi per coprire un intero argomento storico. Gli italoamericani non l'avevano ancora fatto.

Quando UNICO National, una grande organizzazione italoamericana che ha sponsorizzato una serie di cattedre e istituti per gli studi italiani nelle università americane, mi ha chiesto che cosa si sarebbe potuto fare per coronare i loro sforzi, ho suggerito di fare un libro come questo che includesse i contributi di vari esperti del settore. Ho immaginato che qualcun altro si sarebbe poi incaricato di lavorarci, ma quando hanno chiesto a me di farlo, ho coinvolto Stan, in primis perché è un amico, ma anche perché Stan ha fatto un lavoro dettagliato su periodi più recenti di questa storia, mentre io ho lavorato molto sui periodi precedenti: così insieme abbiamo messo su davvero un buon team.

Stan: Penso che sia stato molto ambizioso, ma anche necessario. In ogni classe in cui insegno, chiedo agli studenti di esercitarsi a fare ipotesi, come: "Immaginate di svegliarvi domani e di aver dimenticato tutto di voi stessi: il vostro nome, la vostra famiglia, la vostra etnia, la vostra religione. Sareste la stessa persona che eravate prima di addormentarvi?" E si rendono conto che no, non sarebbero la stessa persona.

Poi cerco di portarli ad estrapolare da questo concetto. E se un'intera civiltà o un intero gruppo etnico dimenticasse la sua storia, quali sarebbero le conseguenze di un simile fenomeno? Non credo che gli italoamericani abbiano rischiato di perdere la loro, la nostra storia, ma penso che rischiamo di non ricordare la nostra storia con tutte le sue sfumature, con tutta la sua complessità. Penso che la comunità italoamericana ora, dopo più di 100 anni dal suo primo arrivo, sia politicamente, economicamente, psicologicamente, socialmente in una situazione da cui possiamo guardare indietro al nostro passato con tutte le sue virtù e i suoi difetti, e mettere insieme qualcosa come questo libro.

Inoltre, è importante anche perché nessuna singola persona poteva fare qualcosa di simile: doveva essere uno sforzo collettivo. Siamo quindi straordinariamente grati alle tre dozzine di collaboratori, ai nostri colleghi, amici e studiosi di tutto il mondo, che sono andati davvero oltre quanto richiesto loro. E Bill, che è stato il responsabile nel riunire tutte queste persone e lavorare insieme, ha davvero realizzato qualcosa di straordinario.

Avete scelto un percorso? Forse uno tematico, o uno geografico? O forse avete seguito una cronologia?

Bill: Sì, c'è una sorta di percorso, sicuramente uno schema cronologico, anche se molti dei capitoli sono tematici. Ci sono quattro parti, nel libro. La prima parte è dedicata all'esplorazione, la seconda all'arrivo negli Stati Uniti e alla realizzazione delle "Little Italies", la terza parte è dedicata al divenire americani e la quarta alle esperienze più recenti degli italoamericani.

Avete messo insieme moltissimi autori, qualcosa che solo persone che hanno carisma e riconoscimento da parte dei loro colleghi accademici sarebbero in grado di fare. Gli italiani non sono noti per partecipare facilmente ad uno sforzo comune. Come siete riusciti a mettere insieme 37 autori italoamericani e anche italiani di incredibile talento, e come siete riusciti a farne uscire un libro coerente, ben calibrato e completo?

Stan: Devo dire che, a testimonianza delle capacità organizzative di Bill, credo che nessuno di coloro ai quali abbiamo proposto di partecipare ci abbia detto di no. In realtà, eravamo in imbarazzo per l'eccesso di autori, e abbiamo dovuto rinunciare ad invitarne alcuni che pure avremmo voluto includere. Ma sarebbe stato quasi impossibile inserire tutti. Penso che abbiamo fatto un ottimo lavoro per coprire moltissimi argomenti, sia quelli che si suppone siano di comune conoscenza, sia cose che la maggior parte degli italoamericani e americani potrebbero non sapere. E devo dire che tutti sono stati davvero molto gentili e pazienti circa i nostri suggerimenti e tutto ciò che abbiamo chiesto loro. E' davvero meraviglioso che si sia rivelato un progetto così piacevole su cui lavorare, anche se è stato un lavoro straordinariamente ampio.

Bill: Una cosa importante da aggiungere – una cosa attesa da tempo, ma meravigliosa - è che ora c'è un serio interesse in Italia per la storia degli italoamericani e della diaspora italiana. Si tratta di un'area di ricerca in crescita all'interno del mondo accademico italiano. E abbiamo fatto uno sforzo speciale per includere alcuni autori italiani, sia traducendo il loro lavoro in inglese, sia reclutando gli italiani che scrivono in inglese. C'è quindi un aspetto internazionale che non si ritrova in nessuno dei precedenti racconti degli italoamericani.

Sono d' accordo con te, questo libro è importante anche per l'Italia. Sarà pubblicato anche in italiano qui in Italia?

Bill: Se c'è un editore in Italia che è interessato, saremo lieti di fare tutto ciò che è necessario. Alcuni capitoli sono stati scritti originariamente in italiano, il che può rendere le cose un po' più facili. Il libro sarà una risorsa ideale per i ricercatori italiani interessati a studiare gli italoamericani.

Bill, la tua introduzione inizia con questa frase: «E' stato negli anni' 80 che gli italoamericani finalmente "ce l'hanno fatta" nella società americana». Per cortesia, spiegaci perché

Bill: E' importante realizzare i progressi che gli italoamericani hanno compiuto in termini di status sociale. Negli anni 1880 e 1890, l'immagine degli italoamericani era molto negativa. Abbiamo capitoli che parlano del linciaggio degli italoamericani, della discriminazione che hanno dovuto affrontare, delle vignette che li ritraevano come ruffiani e gangster. Gli italiani erano sentiti da molti come estranei, come inferiori.

La situazione cominciò a cambiare solo durante la seconda guerra mondiale, quando si verificò una grande integrazione degli italoamericani nella società americana. Dopo la seconda guerra mondiale la presenza italiana nella cultura americana ha continuato a crescere, grazie a cantanti come Frank Sinatra, e grazie al cibo: piatti italiani come gli spaghetti e la pizza, che negli anni '50 sono diventati punti di riferimento della dieta americana. Entro il 1963 o il 1964 gli italoamericani potevano ragionevolmente prevedere che questo ruolo nel mainstream americano sarebbe continuato a crescere.

Tuttavia, la fine degli anni '60 e '70 fu un periodo molto difficile per gli italoamericani. In molti lasciarono le città, in quella che fu chiamata la "fuga etnica bianca". Ci furono tensioni con altri gruppi etnici, con gli afroamericani e i portoricani. L'immagine della mafia si diffuse nella società americana negli anni' 70.

Così ci fu un passo indietro, ed è stato solo negli anni' 80 che giornali e riviste cominciarono ad annunciare che gli italoamericani "ce l'avevano fatta", o, come hanno detto alcuni storici, sono "diventati bianchi". Certo, c'è una certa ironia in questo. Si pensi, prima di tutto, a chi non "ce l'ha fatta"; e poi ci sono anche le modalità con cui gli italoamericani conservano tutt'oggi una particolare identità. Sono solo "ordinari" americani oggi? Questa è una domanda che gli autori di questo libro si trovano a dover affrontare di continuo.

Stan: Se posso aggiungere qualcosa ... quando insegno il mio corso di storia italoamericana, spesso comincio il primo giorno di lezione dicendo ai miei studenti: "Se avessi avuto una conversazione 100 anni fa, nel 1917, e avessi detto a qualcuno che entro la fine del XX secolo ci sarebbero stati non uno ma ben due italoamericani giudici nella Corte Suprema, avrebbero pensato che io fossi impazzito".

Come dice Bill, all'arrivo degli anni' 80 abbiamo governatori, politici e giudici della Corte suprema italoamericani. Si tratta di una storia importante di per sé, ma il rovescio della medaglia è il rischio di dimenticare un passato. A volte si deve pagare un prezzo per diventare mainstream.

Non riesco a scegliere tra i diversi saggi del libro: tutti sono di bellissima scrittura, molto interessanti, e ognuno affronta un tema fondamentale per la comunità italoamericana. Qual è la cosa più curiosa o interessante per voi, che avete imparato lavorando sul libro?

Stan: Sono arrivato agli studi italoamericani partendo dagli studi italiani, quindi ho avuto una certa particolare prospettiva. Conoscevo l'incredibile diversità della cultura italoamericana. Eppure, penso che questa mia conoscenza sia stata davvero rafforzato attraverso i saggi di questo libro: come l'esperienza a New York fosse molto diversa da quella di New Orleans, come fosse diversa a San Francisco, come ci fossero comunità in luoghi come le città minerarie del Colorado, o piantagioni di coltivazioni nel sud americano, o le fabbriche di sigari in Florida. E così, quello che mi ha fatto riflettere è stato questo rinnovato apprezzamento per la resilienza della cultura italoamericana, che ha generato in me una domanda: qual è l'elemento della cultura italiana che ha reso possibile il successo nella cultura italoamericana? Penso che sia stata soprattutto la cultura del Mezzogiorno, l'Italia meridionale, la civiltà da cui sono venuti i miei genitori, che ha permesso loro di attraversare migliaia di chilometri di oceano in un paio di settimane e di affermarsi in una cultura completamente diversa. Penso che se si guardano complessivamente i saggi, anche se ognuno di loro è un piccolo gioiello in sé, questo è il complesso ritratto che forniscono, quello di una trasformazione sociologica, storica e psicologica davvero straordinaria.

Bill: Dove questo lavoro è stato più rivelatore per me, e mi ha aperto a temi che non avevo mai studiato prima, è nei racconti dell'esperienza delle donne italoamericane. Per esempio, nell'analisi passata della vita di chi emigrò c'è stata una grande enfasi sulla povertà e sulle squallide condizioni di vita delle emigrate nelle Little Italies. Ma le cose andavano ancora peggio per le donne, quando vivevano nel sud Italia e in Sicilia. Quando arrivarono a Little Italy trovarono un mondo sociale più esteso, messo a loro disposizione. Per queste donne immigrate, la capacità di fare soldi attraverso la tessitura e il ricamo fu una liberazione. Le donne socializzarono l'una con l'altra in un modo che non riuscivano a fare nelle loro case isolate in villaggi rurali sperduti in Italia e in Sicilia. L'esperienza speciale delle donne italoamericane è testimoniata dai capitoli dedicati alle memorie, ai diari e ai romanzi che le nostre autrici Mary Jo Bona e JoAnne Ruvoli esplorano nei loro saggi. Ciò mi ha particolarmente interessato e arricchito.

Stan, senza svelare nulla che possa rovinarne la lettura, ci dici come mai hai chiamato la tua conclusione "Il futuro del nostro passato?"

Stan: La conclusione non è un tentativo di previsione o di profezia per il futuro. Qualunque rappresentazione del futuro della comunità italoamericana che volessimo presentare sarebbe probabilmente sbagliata. Quello che spero, nella conclusione, è aver fatto sì che i lettori della comunità italoamericana pensino a questo libro non come ad un culmine, ma come l'inizio di qualcosa: due o tre generazioni di studiosi che lavorano insieme, aprendo nuove strade, nuovi modi di pensare all'esperienza italoamericana, che si tratti di genere, che si tratti di studi culturali, che si tratti di architettura o di politica.

Ecco perché credo che sia nostro dovere pensare alla storia italoamericana in modo diverso. Fu Benedetto Croce, richiamando Giambattista Vico, che disse: "L'unico modo per conoscere davvero qualcosa è scriverne la storia". Se non scriviamo la nostra storia, qualcun altro lo farà. Questo è più che altro un manifesto per gli italoamericani, che li spinga ad essere più coinvolti nella scrittura della nostra storia, nel modo in cui siamo rappresentati nei media, nei libri di testo, nella letteratura e nella cultura generale.

Ultima domanda: cosa pensate dei ripetuti attacchi contro Cristoforo Colombo? Cosa dovrebbe fare la comunità italoamericana?

Bill: Questa storia inizia nel 1492. Il punto non è solo che Colombo, Vespucci e altri esploratori erano italiani. Se è vero che i primi viaggi sull'Atlantico si svolgevano sotto le bandiere delle nazioni atlantiche, quello che non è stato sufficientemente riconosciuto è che i finanziamenti per queste spedizioni provenivano da capitali di ventura italiani. Così, storicamente parlando, la scoperta del Nuovo Mondo è stata un'impresa più "italiana" di quanto solitamente si riconosca. Quanto a ciò che è accaduto di conseguenza, per quanto riguarda la festa del Columbus Day, occorre riconoscere che questa è storia, che è avvenuta molto tempo fa. La storia lascia ovviamente spazio al rimpianto e al lutto, ma ciò non significa che il passato e i suoi lasciti vadano dimenticati.

Recentemente gli organizzatori della sfilata del Columbus Day a New York mi hanno consultato circa come trattare le questioni storiche di Colombo. Ho detto loro che dovrebbero davvero fare due cose. In primo luogo, rilasciare una dichiarazione molto forte, riconoscendo che come molte persone nella storia, Colombo ha fatto alcune cose che anche allora erano moralmente inaccettabili e lo sono ancora oggi. In realtà Colombo fece alcune cose terribili in qualità di viceré sull' isola di Hispañola nel 1499 e nel 1500, che portarono alla sua rimozione, e gli storici degli ultimi anni hanno continuato a scoprire più misfatti in documenti negli archivi in Spagna. Ma ciò che Colombo fece nel 1492 creò effettivamente il mondo in cui viviamo oggi. E' stato un momento importante nella storia del genere umano e di questo pianeta, come la scoperta dell'agricoltura. Sembrerebbe un motivo sufficiente per commemorarlo.

La mia seconda raccomandazione, se vogliamo che questa sia una festa nazionale, è stata quella di fare uno sforzo forte per includere altri gruppi etnici, specialmente i nativi americani. Ho fatto notare che nel 1892 a New York, quando l'enfasi era posta sulle scuole e sull'educazione pubblica, che era una novità di allora, la sfilata comprendeva bambini di tutte le scuole e tutte le nazionalità. C'era la Scuola Italiana Dante Alighieri, ma anche la Scuola Indiana Carlisle della Pennsylvania. Così, c'erano scuole italiane e native americane che marciavano insieme nella sfilata del Columbus Day.

Stan: Vorrei solo aggiungere che penso che la comunità italoamericana sia o debba essere a un punto in cui possiamo guardare indietro la nostra storia con un occhio più critico - non che dobbiamo criticare tutto, ma capire che le cose sono un po' più complesse. Così, ad esempio, lasciando da parte le critiche al suo comportamento nel Nuovo Mondo e sulla schiavitù, basti pensare al cambiamento epocale portato da Colombo e dalla sua esplorazione, che segnò fondamentalmente la fine del dominio delle città-stato italiane sulla cultura europea. Si passò dalle città-stato di Genova, Venezia e Milano e altre che erano il centro della vita politica, culturale ed economica dell'Europa, ad un focus spostato sull'Atlantico, con l'America che è diventata la forza dominante nel mondo. C'è un'enorme ironia storica nel fatto che sia stato un "italiano" il responsabile del "declino" dell'Italia nel mondo moderno. Così, in un certo senso, Colombo è un microcosmo della complessità della cultura italoamericana. Certo, dovremmo celebrare i nostri successi nel trionfo, ma allo stesso tempo dobbiamo riconoscere che a volte questi trionfi e successi sono un po' più complicati di quello che pensiamo.

E su questo cosa dovrebbe fare l'Italia, se deve fare qualcosa, secondo voi?

Stan: Come ha detto Bill, ci siamo sforzati di coinvolgere le giovani generazioni di studiosi italiani che lavoravano sugli studi italoamericani. Per troppo tempo gli studiosi italiani avevano considerato la cultura italoamericana come remota, qualcosa che non meritava nemmeno la loro attenzione, rifiutandosi di rendersi conto che il numero degli italiani che vivono fuori dall'Italia è pari al numero di coloro che vivono in Italia. Questo è cambiato, e la prova sono gli studiosi italiani nel nostro volume. Per quanto riguarda Colombo, penso che anche l'Italia debba assumersi una qualche responsabilità nel dimostrare l'incredibile impatto di Colombo sul mondo: intendo dire che il mondo moderno non esisterebbe senza di lui, con tutta la complessità morale, politica ed etica che egli incarnava.

Bill: Per continuare il pensiero di Stan, c'è un processo di maturazione che sta succedendo tra gli italoamericani. Come dice Stan, essi hanno raggiunto uno stato in cui possono criticare sé stessi e accettare anche le critiche di altri. Ora è giunto il momento di un maturo riconoscimento della complessità della storia, sia da parte degli italoamericani che degli italiani in Italia, che sono oggi sempre più spesso dalla parte ricettiva dell'esperienza dell'immigrazione di massa.