Sometimes it happens that I find out about the story of a person who personifies exactly the message that We the Italians has been representing for 10 years now: when Italy and the United States come together, the result is wonderful. Other times I have the pleasure of interviewing people who embody one or more positive symbols of Italy. Still other times, I happen to interview someone whose story, talent and well-deserved success represent the answer to some of our country's atavistic problems.

The great Italian who has done me the honor of being the protagonist of this new interview is so exceptional that she corresponds to all three of the above categories, and this is still not enough to describe her talents, her successes and her Italianness. This is why I am happy, proud and very grateful to welcome on We the Italians an extraordinary Italian scientist: Anna Grassellino. It is only by chance that this interview is published the day after an Italian has won the Nobel Prize for Physics. But let's say that the hope is that it will be a good omen so that the next Italian Nobel Prize in the field of science will be just her.

From Marsala, Sicily to Chicago, Illinois. This is a travel that many Italians have done in the past, but with completely different stories than yours … please tell us more about you

Yes. I left my hometown Marsala when I was 17, I guess. I went to study electronic engineering at University of Pisa. A year before graduating from Pisa, I actually wanted to do an internship abroad, I wanted to really see and learn how research was done somewhere else outside Italy.

At that time, there was a summer internship for INFN, National Institute for Nuclear Physics. Only nine people in Italy were selected to go to Fermilab as summer students. So I came to Fermilab for my first time in 2004, as a summer student, the year before my master graduation. And I really loved it. I loved everything about it, I found the US fascinating, and I found Fermilab in particular really a wonderful place because of such an international environment of people from all countries coming together to build the most complex experiment on the planet.

There were several professors looking for PhD students, one of which was Nigel Lockyer who is today the director of Fermilab. At that time, Nigel was a professor at University of Pennsylvania. Nigel was looking for students to work on the International Linear Collider and I was a good fit, because there was a need for electronic engineers working on electronics controls. That's how my journey started. I applied to University of Pennsylvania, and I got admitted into the Ph. D. program at University of Pennsylvania. So I graduated from University of Pisa with my masters in 2005 and a month later and I was already here for my PhD in Philadelphia.

Philadelphia was a nice chapter. I was there for two years approximately. I did my master’s in physics there and then Nigel became director of TRIUMF, the Canada's national lab for nuclear physics. I was offered the opportunity to move to Vancouver and do my PhD thesis there as I was done with classes. So I went to Vancouver, and I was lucky that I could do my PhD thesis on a real accelerator, at TRIUMF.

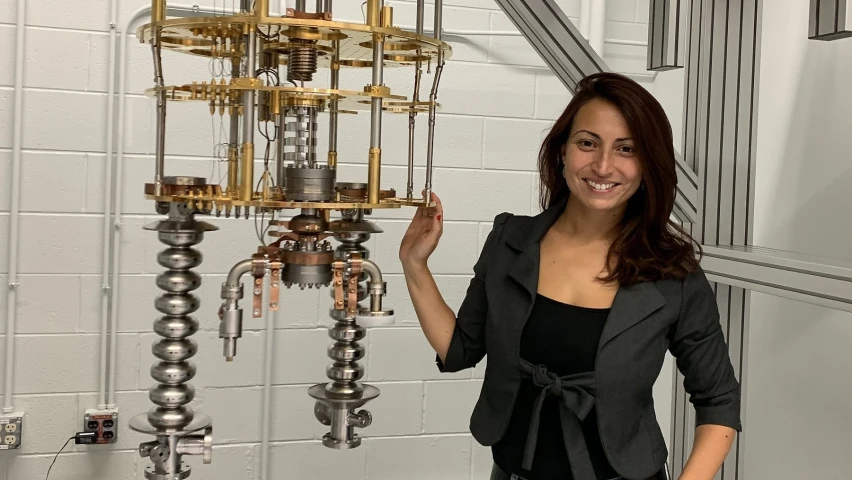

And then I was hired at Fermilab back in 2012. First as a postdoc, then I became an associate scientist, then scientists, then senior scientists. And also since the past few years, on top of research responsibility, I have also some management responsibilities. Years ago I became deputy head of the Applied Physics and Superconducting Technology Division of Fermilab: that's a really important division at Fermilab, I think the second largest. This is where we advance the technologies for particle accelerators, superconducting cavity, superconducting magnets, and cryogenic: for example, we develop the technologies and we build the particle accelerator for our complex but also for labs all across the globe.

A couple years ago we started to work on accelerators also to be used in the field of quantum computing, and we became the best at making this. This is the foundation from which we applied to the National Quantum Center, which we were awarded last year. When that happened I became director of this new National Quantum Center. It's been less than a year, but it's been a very exciting journey. So that's kind of like my long journey from Marsala, Sicily, all the way to Chicago today.

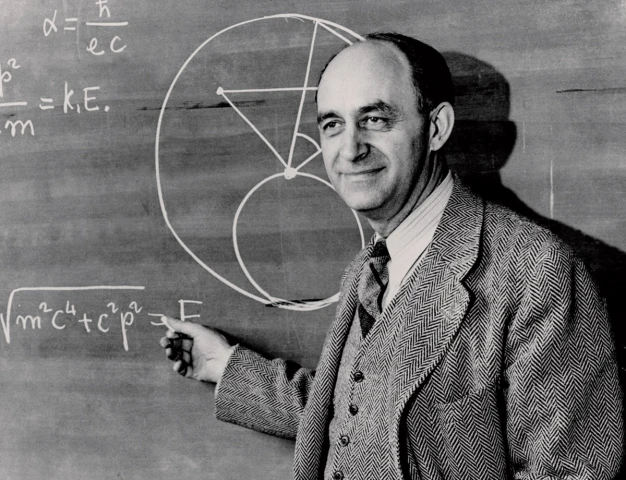

Let’s talk about Fermilab. We are proud that there is such an important facility in the United States named after an Italian scientist. We ask you to briefly describe to our readers what Fermilab is, when it was born and what is its mission

Yes, it's a reason for pride for all of us Italians, actually the percentage of Italians here is quite high. We have a lot of Italians, also in leadership positions. Fermilab is the US high energy physics laboratory. So we are really the one laboratory that is fully funded by the Department of Energy Office of Science at High Energy Physics. 98% of our funding comes from High Energy Physics, which means 98% of what we do, really goes towards fundamental understanding the microscopic world that surrounds us, so the world of particles.

The history of Fermilab dates back more than 50 years, when Fermilab was founded. The idea was to build a revolutionary machine that would allow to smash particles and really study the fragments to understand what matters is made of. Fermilab invented a lot of technologies that today have an impact broadly on society.

To help me and the readers of We the Italians who aren't experts in physics and quantum computing: what are the innovations that will come into our future daily lives from the work you are doing?

For example, for the Quantum Endeavor, the center that now I am Director of we are building the most powerful quantum computer in the world. A quantum computer is a computer that will be much more powerful than classical computers for certain applications, almost like comparing a car to an airplane. So not an old car with a new car, but really a car with an airplane. One of the areas where the quantum computers will be able to do what the classic computers don’t is, for example, in the field of national security, in cryptography. If there’s an encryption that even the largest and most powerful supercomputer in the world would need hundreds and hundreds of years to decode, a quantum computer will be able to do that in few minutes.

The part that interests us the most is in science and in medicine. Quantum computer could be able to solve and do some incredible simulations. For example on proteins, molecules interacting with each other. It could open a lot of potential avenues in the field of medicine, for example. Even in physics itself it may help us: when we smash particles we then have to reconstruct these events still with a classical computer, and from there, run some models and try to understand. But the quantum computer works based on principles that are closer to how particles behave, the laws that govern a particle. And so in reality, quantum computers may help us interpret differently even atoms collisions. Maybe the data we already possess could be looked with different glasses, and maybe we could be able to see things that otherwise we haven’t seen before in the way we have analyzed those data. Cell phones or computers, but actually everything works based on fundamental laws of physics. A revolution on our knowledge about this could bring a revolution in our everyday’s life.

The collaboration between Italy and the United States in the scientific field is very advanced. Is this also happening in the project you are leading?

Yes. The center that I'm directing, it's composed of 20 partners. And the United States Department of Energy was very happy when we proposed that one of the partners would be actually the Italian National Institute for Nuclear Physics (INFN). In the whole quantum initiative in the US there's only two international partners: one is Italy, and one is Canada. I think this says a lot about the strong relationship between the US and Italy. Fermilab and INFN have being collaborating for many years, in neutrino physics, in particle physics, and now in quantum computing: we actually have more than a dozen collaborators from INFN participating actively in our project. We will be testing some of the devices and structures that we make at the Gran Sasso laboratory, which has an underground facility that is unique in the world. Also we have collaboration with Italian laboratories and structures from Rome, Frascati, Padova and Pavia. We are also looking now into expanding partnership with the University of Milan Bicocca and with University of Pisa.

Dr. Grassellino, please correct me if I'm wrong. You are building the most powerful quantum computer in the world. To do so you are the leader of a team that manages $115 million, with 200 scientists. You just turned 40. You are a wife and mom of three. What’s your secret?

I think Fermilab has helped me out a lot in the sense that, for example, we have daycare on site. It's true that having kids and trying to do all this is not easy. Fermilab having a daycare on site has been critical, like we brought our kids to the daycare when they were like six to 12 weeks, very little, but I was still able to go and see them. So that has been a big help. And of course my husband has been a great help, too. We are a very good team. Between us it has never been either about my or his career, it has always been a teamwork to try to be both successful.

But you must have a secret. I mean, maybe there's something in your DNA, maybe because you're Italian, maybe because you're Sicilian. I don't know how you do it all at the same time…

One important thing is that I've always been a person who is never happy with the status quo. I always feel the urge to do more, to push for the next step and to be looking at the future. So I think that has always been a big push, and it’s the same for my husband. So our teamwork is not just at home: he's a scientist here as well. He is the Chief Technology Officer at Fermilab. We work as a team when we really try to make new discoveries, to build new facilities for the next generation. We both have a great team that we have put together, with many other Italians as well together with scientists from all around the world.

Can you also find time to hang out with the Italian community in Chicago? Is there a place of where you live now that in a way remembers you of Italy?

I put some effort a few years ago. Lately, I have to say, I don’t have as much time, frankly: but a few years ago I did connect and had a chance to hang out with many fellow Italians from the Italian community in Chicago. They do a wonderful job to celebrate and represent Italy in this area.

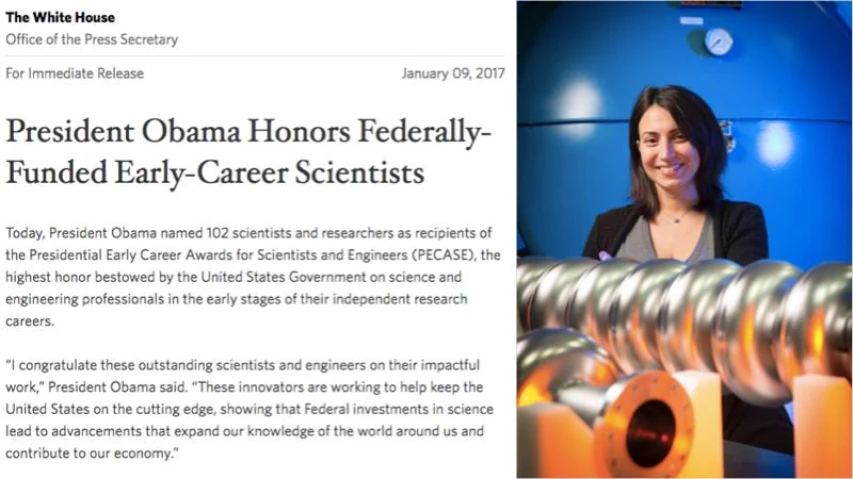

Italy has given birth to great researchers and scientists who are praised in the United States. When President Obama awarded you with the Presidential Early Career Awards for Scientists and Engineers, he said that you were one of the most promising young person on earth. What does Italy have to do, and what has Italy not yet done, and what do you hope it will do, to stop sending so many brilliant young minds away, and to ensure that you and others like you find the right environment to return one day?

I thank you for not using the phrase “brain drain”, which is usually used in questions like this. I don't feel that we are brains. What is a brain drain? It's a good thing that we go from Italy to other parts of the world. First of all, we raise our flag in the world and remind everyone how talented Italians are: I don't think that there is a doubt about that. I think we Italians have a very special talent in science. And so I think it's great that we go abroad, and we show that and we actually further improve, because we draw on diversity, right? We learn from going out and seeing how other countries think and do things, and from interacting with other people.

Yes, maybe what would be best is that Italy also would move a little more on this model like the US. Yes, it would be nice not just to give, but also to take: to host scientists from other countries, too. I think that is where we're lacking a little bit. Some realities in Italy are pretty international, but some else should do more. Our culture, I think has to change in that.

For instance, let’s consider the fact that we are not as proficient as other countries in speaking English. I think that has to change because it makes a difference for people to come and not feel an outsider. If there is a universal language that everybody speaks, we need to learn that. Here in the US I learned the advantage of being able to listen and learn and take from others, and on this matter Italy can do better.

Another thing that should change in Italy are salaries. Of course the research funds here in the US are huge, there is no denying that, and that is one reason why many people come here and don’t go to Italy. But I think that Italy should invest more in paying researchers, and consider what their career could be, especially in science. If the prospect is to be on a temporary researcher status with a tiny salary for decades, that is not very appealing. That’s a big reason why people explore opportunities somewhere else.

You are undoubtedly an Italian excellence who has found in the US the ideal environment to be valued as you deserve. Your DNA, your schooling and the environment made up of people, places and culture in the broadest possible sense you grew up in, have been fundamental in cultivating your talent and your desire to innovate, improve and learn. I consider you an extraordinary scientist but also a success of our country, in the sense that I believe and hope that there is a lot of Italy in you. I don't know if We the Italians has the right to be proud of a person like you, I hope so because that's how we feel. Am I wrong?

I think that the school system in Italy is outstanding, much better than other countries. I think I was formed in a way that really brought me to analytical thinking. By studying Latin, I learnt a lot of things that otherwise I wouldn't have studied. And then the university as well: University of Pisa gave me a really strong background. And of course, it was not like in the US where you have to do everything pretty much alone to be able to have loans you’ll have to repay in the future if you ant to keep on studying. I'm thankful that in Italy I was able to study without investing that much. I will be forever thankful for that. And I will be forever thankful for the fact that I felt so much affection really from Italy for the achievements that I've had. So I think that Italy has been amazing for me and has given me a big push.

In 2020, in the Italian universities, compared to a male enrollment rate of 48.5 %, the female enrollment rate was 65.7 %. Enrolled women are more, and growing at a fastest rate. The number of freshmen increased above all in the Central (+7.7%) and Southern (+5%) regions. 29.9 % of these new Italian students signed up in a STEM course (as to say Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics). You are a woman, a scientist, a southern Italian: you represent three symbols of needed change for Italy, all at once. What would you say to a young girl from southern Italy who dreams of a career like yours?

What I would say is to really embrace the American philosophy of "Yes, you can." Don't be afraid. Don't think that there are things that are not achievable, because anything can be achieved. I think this is absolutely the most important thing that I can say. Sometimes young women can get discouraged. But I think things are changing. And I think people are working on changing things. And so don't get discouraged and really try and reach out and look beyond and don't be afraid to send an email and say “I would like to do this” or walk into an office of someone important and say "I think I can do this, can I participate? Can I do this PhD? Can I get this job?" I think that this is the most important message.

A volte capita di scoprire la storia di una persona che rappresenta esattamente il messaggio che ormai da 10 anni We the Italians rappresenta: quando Italia e Stati Uniti si uniscono, il risultato è meraviglioso. Altre volte mi succede di avere l'onore di intervistare persone che incarnano uno o più simboli dell'Italia, in senso positivo. Altre volte ancora, mi è capitato di intervistare qualcuno che rappresenta con la sua storia, il suo talento e il suo meritato successo, la risposta ad alcuni problemi atavici del nostro Paese.

La grande italiana che mi ha fatto l'onore di essere la protagonista di questa nuova intervista è talmente eccezionale che corrisponde a tutte e tre le categorie sopra descritte, e ciò non basta ancora a descrivere le sue doti, i suoi successi e la sua italianità. E' per questo che sono felice, orgoglioso e molto grato di poter dare il benvenuto su We the Italians ad una straordinaria scienziata italiana: Anna Grassellino. E' solo un caso se questa intervista viene pubblicata il giorno dopo che un italiano ha vinto il Premio Nobel per la Fisica. Ma diciamo che la speranza è che sia di buon auspicio affinché la prossima Premio Nobel italiana nel campo delle scienze sia proprio lei

Da Marsala, Sicilia a Chicago, Illinois. Questo è un viaggio che molti italiani hanno fatto in passato, ma con storie completamente diverse dalle sue... ci racconti di più di lei

Sì, ho lasciato la mia città natale Marsala quando avevo 17 anni, credo. Sono andata a studiare ingegneria elettronica all'Università di Pisa. Un anno prima di laurearmi a Pisa volevo fare uno stage all'estero, volevo davvero vedere e imparare come si faceva ricerca da qualche altra parte fuori dall'Italia.

A quel tempo, c'era uno stage estivo per l'INFN, Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare. Solo nove persone in Italia venivano selezionate per andare al Fermilab come studenti durante l’estate. Così sono venuta al Fermilab per la mia prima volta nel 2004, per un corso estivo, l'anno prima della mia laurea magistrale. E mi è piaciuto molto. Mi è piaciuto tutto, ho trovato gli Stati Uniti affascinanti, e ho trovato il Fermilab in particolare davvero un posto meraviglioso per via di un ambiente così internazionale di persone provenienti da tutti i paesi che si riuniscono per costruire l'esperimento più complesso del pianeta.

C'erano diversi professori che cercavano studenti di dottorato, uno dei quali era Nigel Lockyer che oggi è il direttore del Fermilab. A quel tempo, Nigel era professore all'Università della Pennsylvania. Nigel cercava studenti per lavorare all'International Linear Collider e io ero adatta, perché c'era bisogno di ingegneri elettronici che lavorassero sui controlli elettronici. È così che è iniziato il mio viaggio. Ho fatto domanda all'Università della Pennsylvania e sono stata ammessa al loro programma di dottorato. Così mi sono laureata all'Università di Pisa con il mio master nel 2005 e un mese dopo ero già qui per il mio dottorato a Philadelphia.

Philadelphia è stato un bel capitolo. Sono stata lì per due anni circa. Ho fatto lì il mio master in fisica e poi Nigel è diventato direttore di TRIUMF, il laboratorio nazionale canadese di fisica nucleare. Mi è stata offerta l'opportunità di trasferirmi a Vancouver e fare la mia tesi di dottorato lì, visto che avevo finito le lezioni. Così sono andata a Vancouver, e sono stata fortunata a poter fare la mia tesi di dottorato su un vero acceleratore, al TRIUMF.

E poi sono stata assunta al Fermilab nel 2012. Prima come post-dottorato, poi sono diventata scienziata associata, poi scienziata, poi scienziata senior. E da qualche anno, oltre alla responsabilità della ricerca, ho anche alcune responsabilità di gestione. Anni fa sono diventata vice capo della Divisione di Fisica Applicata e Tecnologia Superconduttiva del Fermilab: è una divisione davvero importante al Fermilab, credo la seconda più grande. È dove facciamo progredire le tecnologie per gli acceleratori di particelle, le cavità superconduttrici, i magneti superconduttori e la criogenia: per esempio, sviluppiamo le tecnologie e costruiamo l'acceleratore di particelle per il nostro complesso ma anche per i laboratori di tutto il mondo.

Un paio di anni fa abbiamo iniziato a lavorare sugli acceleratori anche per essere utilizzati nel campo del calcolo quantistico, e siamo diventati i migliori a farlo. Questa è la base da cui abbiamo fatto domanda per il National Quantum Center, che ci è stato assegnato l'anno scorso. Quando è successo, sono diventata direttrice di questo nuovo National Quantum Center. È passato meno di un anno, ma è stato un viaggio molto emozionante. Quindi questo è il mio lungo viaggio da Marsala, Sicilia, fino a Chicago oggi.

Parliamo del Fermilab. Siamo orgogliosi che negli Stati Uniti ci sia una struttura così importante che porta il nome di uno scienziato italiano. Le chiediamo di descrivere brevemente ai nostri lettori cos'è il Fermilab, quando è nato e qual è la sua missione

Sì, è un motivo di orgoglio per tutti noi italiani, anzi la percentuale di italiani qui è abbastanza alta. Abbiamo molti italiani, anche in posizioni di leadership. Fermilab è il laboratorio americano di fisica delle alte energie. Siamo l'unico laboratorio che è completamente finanziato dal Dipartimento dell'Energia Ufficio della Scienza per la Fisica delle Alte Energie. Il 98% dei nostri finanziamenti proviene dalla Fisica delle Alte Energie, il che significa che il 98% di ciò che facciamo va verso la comprensione fondamentale del mondo microscopico che ci circonda, quindi il mondo delle particelle.

La storia del Fermilab risale a più di 50 anni fa, quando fu fondato. L'idea era quella di costruire una macchina rivoluzionaria che permettesse di frantumare le particelle e studiare i frammenti per capire di cosa è fatta la materia. Il Fermilab ha inventato molte tecnologie che oggi hanno un ampio impatto sulla società.

Per aiutare me e i lettori di We the Italians che non sono esperti di fisica e quantum computing: quali sono le innovazioni che arriveranno nella nostra futura vita quotidiana dal lavoro che state facendo?

Per esempio, per il Quantum Endeavor, il centro di cui ora sono direttrice, stiamo costruendo il più potente computer quantistico del mondo. Un computer quantistico è un computer che sarà molto più potente dei computer classici per certe applicazioni, quasi come paragonare un'auto a un aeroplano. Quindi non un'auto vecchia con un'auto nuova, ma proprio un'auto con un aeroplano. Una delle aree in cui i computer quantistici saranno in grado di fare ciò che i computer classici non fanno è, per esempio, nel campo della sicurezza nazionale, nella crittografia. Se c'è una crittografia che anche il più grande e potente supercomputer del mondo avrebbe bisogno di centinaia e centinaia di anni per decodificare, un computer quantistico sarà in grado di farlo in pochi minuti.

La parte che ci interessa di più è nella scienza e nella medicina. Il computer quantistico potrebbe essere in grado di risolvere e fare delle simulazioni incredibili. Per esempio sulle proteine, le molecole che interagiscono tra loro. Potrebbe aprire molte strade potenziali nel campo della medicina, per esempio. Anche nella fisica stessa potrebbe aiutarci: quando distruggiamo delle particelle dobbiamo poi ricostruire questi eventi ancora con un computer classico, e da lì, eseguire dei modelli e cercare di capire. Ma il computer quantistico funziona sulla base di principi che sono più vicini a come si comportano le particelle, le leggi che governano una particella. E così, in realtà, i computer quantistici potrebbero aiutarci a interpretare in modo diverso anche le collisioni degli atomi. Forse i dati che già possediamo potrebbero essere guardati con occhiali diversi, e forse potremmo essere in grado di vedere cose che altrimenti non abbiamo visto prima nel modo in cui abbiamo analizzato quei dati. Cellulari o computer, ma in realtà tutto funziona in base alle leggi fondamentali della fisica. Una rivoluzione nella nostra conoscenza di questo potrebbe portare una rivoluzione nella nostra vita quotidiana.

La collaborazione tra Italia e Stati Uniti in campo scientifico è molto avanzata. Questo avviene anche nel progetto che lei sta conducendo?

Sì. Il centro che dirigo è composto da 20 partner. E il Dipartimento dell'Energia degli Stati Uniti è stato molto felice quando abbiamo proposto che uno dei partner fosse proprio l'Istituto Nazionale Italiano di Fisica Nucleare (INFN). In tutta l'attività quantistica negli Stati Uniti ci sono solo due partner internazionali: uno è l'Italia, e l’altro è il Canada. Penso che questo dica molto sulla forte relazione tra gli Stati Uniti e l'Italia. Il Fermilab e l'INFN collaborano da molti anni, nella fisica dei neutrini, nella fisica delle particelle e ora nel quantum computing: abbiamo più di una dozzina di collaboratori dell'INFN che partecipano attivamente al nostro progetto. Proveremo alcuni dei dispositivi e delle strutture che realizziamo al laboratorio del Gran Sasso, che ha una struttura sotterranea unica al mondo. Inoltre abbiamo una collaborazione con laboratori e strutture italiane di Roma, Frascati, Padova e Pavia. Ora stiamo anche cercando di ampliare la partnership con l'Università di Milano Bicocca e con l'Università di Pisa.

Dottoressa Grassellino, la prego di correggermi se sbaglio. Lei sta costruendo il più potente computer quantistico del mondo. Per farlo guida un team che gestisce 115 milioni di dollari, con un team di 200 scienziati. Hai appena compiuto 40 anni. E’ moglie e madre di tre figli. Qual è il suo segreto?

Penso che il Fermilab mi abbia aiutato molto nel senso che, per esempio, abbiamo l'asilo nido in loco. È vero che avere figli e cercare di fare tutto questo non è facile. Il fatto che il Fermilab abbia un asilo nido in loco è stato fondamentale, ad esempio abbiamo portato i nostri figli all'asilo quando avevano tra le sei e le dodici settimane, molto piccoli, ma ero comunque in grado di andare a vederli. Questo è stato di grande aiuto. E naturalmente anche mio marito è stato di grande aiuto. Siamo un'ottima squadra. Tra di noi non si è mai trattato della mia o della sua carriera, è sempre stato un lavoro di squadra per cercare di avere entrambi successo.

Ma lei deve avere un segreto. Voglio dire, forse c'è qualcosa nel suo DNA, forse perché è italiana, forse perché è siciliana. Non so come fa a fare tutto questo contemporaneamente...

Una cosa importante è che sono sempre stata una persona mai contenta dello status quo. Sento sempre il bisogno di fare di più, di spingere per il prossimo passo e di guardare al futuro. Quindi penso che questa sia sempre stata una grande spinta, e lo stesso vale per mio marito. Il nostro lavoro di squadra non è solo a casa: anche lui è uno scienziato qui. È il responsabile della tecnologia al Fermilab. Lavoriamo come una squadra quando cerchiamo di fare nuove scoperte, di costruire nuove strutture per la prossima generazione. Abbiamo entrambi una grande squadra che abbiamo messo insieme, con molti altri italiani insieme a scienziati di tutto il mondo.

Riesce anche a trovare il tempo per frequentare la comunità italiana di Chicago? C'è un posto di dove vive ora che in qualche modo le ricorda l'Italia?

Ho fatto qualche sforzo in questo senso qualche anno fa. Ultimamente, devo dire, non ho così tanto tempo, francamente: ma qualche anno fa ho messo in contatto e avuto modo di frequentare molte persone della comunità italiana di Chicago. Fanno un lavoro meraviglioso per celebrare e rappresentare l'Italia in questa zona.

L'Italia ha dato vita a grandi ricercatori e scienziati che vengono lodati negli Stati Uniti. Quando il presidente Obama l'ha premiata con il Presidential Early Career Awards for Scientists and Engineers, ha detto che lei è una delle giovani persone più promettenti della terra. Cosa deve fare l'Italia, e cosa non ha ancora fatto, e cosa lei spera che faccia, per smettere di mandare via così tante giovani menti brillanti, e per assicurare che lei e altri come lei trovino l'ambiente giusto per tornare un giorno?

La ringrazio per non aver usato la frase "fuga di cervelli", che di solito si usa in domande come questa. Non mi sembra che siamo cervelli. Cos'è una fuga di cervelli? È un bene che si vada dall'Italia in altre parti del mondo. Prima di tutto, portiamo in alto la nostra bandiera nel mondo e ricordiamo a tutti quanto sono bravi gli italiani: non credo che ci siano dubbi su questo. Penso che noi italiani abbiamo un talento molto speciale nella scienza. E quindi penso che sia fantastico che andiamo all'estero, e lo dimostriamo e in realtà miglioriamo ulteriormente, perché attingiamo alla diversità, giusto? Impariamo andando fuori e vedendo come pensano e fanno le cose gli altri paesi, e interagendo con altre persone.

Sì, forse la cosa migliore sarebbe che anche l'Italia si muovesse un po' di più su questo prendendo a modello gli Stati Uniti. Sì, sarebbe bello non solo dare, ma anche ricevere: ospitare anche scienziati di altri paesi. Credo che sia questo il punto in cui siamo un po' carenti. Alcune realtà in Italia sono abbastanza internazionali, ma qualcun altro dovrebbe fare di più. La nostra cultura, secondo me, deve cambiare in questo.

Per esempio, consideriamo il fatto che non siamo così abili come altri paesi nel parlare inglese. Penso che questo debba cambiare perché fa la differenza per le persone che vengono e non si sentono estranee. Se c'è una lingua universale che tutti parlano, dobbiamo impararla. Qui negli Stati Uniti ho imparato il vantaggio di poter ascoltare e imparare dagli altri, e su questo l'Italia può fare meglio.

Un'altra cosa che dovrebbe cambiare in Italia sono gli stipendi. Naturalmente i fondi per la ricerca qui negli Stati Uniti sono enormi, non si può negare, e questo è uno dei motivi per cui molte persone vengono qui e non vanno in Italia. Ma penso che l'Italia dovrebbe investire di più nel pagare i ricercatori, e considerare quale potrebbe essere la loro carriera, soprattutto nella scienza. Se la prospettiva è quella di rimanere nello status di ricercatore temporaneo con uno stipendio minuscolo per decenni, non è molto allettante. Questo è un motivo importante per cui le persone esplorano le opportunità di andare altrove.

Lei è senza dubbio un'eccellenza italiana che ha trovato negli Stati Uniti l'ambiente ideale per essere valorizzata come merita. Il suo DNA, la sua formazione scolastica e l'ambiente fatto di persone, luoghi e cultura in senso lato in cui è cresciuta, sono stati fondamentali nel coltivare il suo talento e la sua voglia di innovare, migliorare e imparare. Io la considero una scienziata straordinaria ma anche un successo del nostro Paese, nel senso che credo e spero che ci sia molta Italia in lei. Non so se We the Italians abbia il diritto di essere orgogliosa di una persona come lei, lo spero perché è così che ci sentiamo. Mi sbaglio?

Penso che il sistema scolastico in Italia sia eccezionale, molto meglio di altri paesi. Penso di essere stata formata in un modo che mi ha portato davvero al pensiero analitico. Studiando il latino, ho imparato molte cose che altrimenti non avrei studiato. E poi anche l'università: l'Università di Pisa mi ha dato un background davvero forte. E naturalmente non era come negli Stati Uniti dove devi fare tutto praticamente da solo per poter avere dei prestiti che dovrai restituire in futuro se vuoi continuare a studiare. Sono grata che in Italia ho potuto studiare senza investire così tanto. Sarò grata per sempre per questo. E sarò per sempre grata per il fatto che ho sentito così tanto affetto dall'Italia per i risultati che ho ottenuto. Quindi penso che l'Italia sia stata fantastica per me e mi abbia dato una grande spinta.

Nel 2020, nelle università italiane, a fronte di un tasso di iscrizione maschile del 48,5%, il tasso di iscrizione femminile era del 65,7%. Le donne iscritte sono di più, e crescono a un ritmo più veloce. Il numero di matricole è aumentato soprattutto nelle regioni del Centro (+7,7%) e del Sud (+5%). Il 29,9% di questi nuovi studenti italiani si è iscritto ad un corso STEM (Scienza, Tecnologia, Ingegneria e Matematica). Lei è una donna, una scienziata, un'italiana del Sud: rappresenta tre simboli di un cambiamento necessario per l'Italia, tutti insieme. Cosa direbbe a una giovane ragazza del sud Italia che sogna una carriera come la sua?

Direi di abbracciare davvero la filosofia americana del "Yes, you can". Non abbiate paura. Non pensate che ci siano cose che non sono realizzabili, perché tutto può essere realizzato. Penso che questa sia assolutamente la cosa più importante che posso dire. A volte le giovani donne possono scoraggiarsi. Ma penso che le cose stiano cambiando. E penso che le persone stiano lavorando per cambiare le cose. E quindi non scoraggiatevi e cercate davvero di raggiungere e guardare oltre e non abbiate paura di mandare un'e-mail e dire "Mi piacerebbe fare questo" o entrare nell'ufficio di qualcuno di importante e dire "Penso di poterlo fare, posso partecipare? Posso fare questo dottorato? Posso ottenere questo lavoro?" Penso che questo sia il messaggio più importante.