The history of the Italian emigrants who left for America is often a history of difficulties, suffering and accidents. Often these accidents occurred in shameful and almost impossible work situations, which were the only ones left for the latest arrivals, the Italians willing to do anything to survive and allow their children to have a better education and a better life. Sometimes there were discriminatory prevarications.

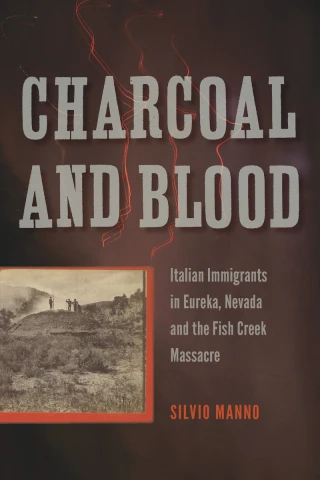

Today we meet Silvo Manno, and we thank him for being here with us: he did research and wrote a book on what was called the "Charcoal and Blood: Italian Immigrants in Eureka, Nevada, and the Fish Creek Massacre", and happened in Nevada. The different thing from other tragic situations is that in this case the problems arose between two factions within the Italian community. It is important to understand what happened, to learn from their stories

Silvio, you are the author of the book “Charcoal and Blood: Italian Immigrants in Eureka, Nevada, and the Fish Creek Massacre”. How did you come up with the idea of this book?

In 1984 I enrolled at California State University of Fresno. As a university student I spent a great deal of time at the campus library. Given my passionate interest about immigration history, I was drawn to the Ethnic and Cultural Studies section of the library. There I chanced upon a book titled Restless Strangers: Nevada's Immigrants and Their Interpreters, authored by Wilbur S. Shepperson, history professor at the University of Reno, Nevada. Intrigued by the title, I scanned the book's index as I did habitually. To my amazement, I came across an entry that read: “Italian Wars.” As I probed deeper, I learned of the Fish Creek Massacre, a gruesome incident that occurred in the summer of 1879, outside Eureka, Nevada, following a confrontation between a heavily armed 9-man sheriff's posse and dozens of destitute Italian charcoal burners (carbonari). The showdown resulted in the death of five Italian immigrants, with several wounded and many arrested. Baffled by the historical silence that had concealed the tragedy for more than a century, silence already lamented by Professor Shepperson, who compared the massacre to “a Sacco and Vanzetti drama,” I vowed to shed light upon the heinous crime omitted from American history. That's when the sentiment for the book first arose. However, many years would pass before the idea would become reality.

We’d like to know more about the Italian emigration to Nevada. Where did those Italian immigrants come from, who were they and how did they get to Nevada?

They came almost exclusively from Italy's northern regions: Lombardy, Piedmont, and Liguria. The California gold rush of 1849 attracted hordes of immigrants from around the world, a sizable number of Italians was also drawn to the goldfields in search of fortune. But, rather than prospecting for the precious metal, most of them went into merchandising, catering to the needs of the “Forty-Niners.” Many of them became prosperous merchants and businessmen. By 1859 California's surface gold (placer) had been exhausted by legions of Argonauts and the lone prospector was replaced by industrial mining financed by wealthy investors.

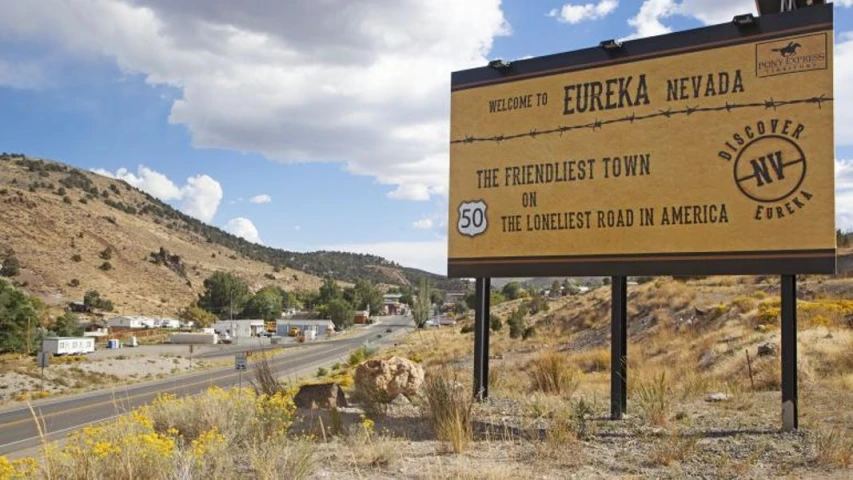

That same year, another spectacular strike shook the mineral frontier, this time in the neighboring state of Nevada, where the world's richest silver deposit, the Comstock Lode, was unearthed. News of the discovery spread far and wide and throngs of fortune seekers rushed to the Silver State (Nevada). Having reaped much prosperity during the California gold rush by providing for the miners' necessities, several Italian merchants hurried to launch new business ventures on the Comstock. Dozens of boom-towns sprung up at lightening speed throughout the region. Preeminent among them rose Virginia City, center where the Italian presence was attested by the prestigious Molinelli’s Hotel, built in the 1870s. As the mineral wealth of the Comstock Lode dwindled, new strikes were avidly sought by both miners and investors. In the early 1870s, the small mining camp of Eureka, in southern Nevada, revealed the largest deposits of lead amalgamated with silver in the United States and perhaps in the world. While abundant, Eureka's ore turned out to be challenging and costly to smelt. The two minerals could be separated only at extremely high temperatures thus requiring vast quantities of charcoal to fuel the smelting ovens. In the early 1870s the charcoal trade was plied solely by the Chinese but as intolerance and persecution against them reached a feverish pitch the Asians were forced to yield the trade to the Italians.

The new arrivals hailed predominantly from Italy's alpine regions, with a lesser number originating from Switzerland's Italian speaking canton Ticino, where charcoal making was a century-old practice. Recruited by compatriots acting as middle men on behalf of American companies as well as Italian entrepreneurs (padroni) in search of cheap labor, prospective immigrants were frequently deceived by overly glowing accounts of easy riches to be found on Nevada's mining frontier. In reality, the desperate and poverty-stricken laborers bound for the American wilderness had unwittingly agreed to enter into a master-servant relationship. By signing the contract the Italian hirelings would incur heavy financial liabilities: repayment of the ocean crossing plus interest, payment for room and board provided by their new employers, wages paid to them in vouchers were only redeemable at the contractors' stores where tools and supplies were abysmally overpriced. Further, their inability to speak English coupled with their unfamiliarity with the dynamics of the American culture greatly hampered their personal autonomy. All these factors exacerbated their reliance upon their bosses (padroni) rendering them even more vulnerable to exploitation.

Although Eureka's Italians were an heterogeneous group of immigrants, they all shared a rural background and the range of occupations therein. Displaced by a backward semi-feudal agricultural system, political instability, increased taxation, and a series of crop failures caused by droughts and floods, a motley crew of desperate contadini heeded the promise of gainful employment on the mineral range of distant Nevada. While not all of them were expert charcoal makers, most became employed in the manufacture of such a valuable resource in the hills outside Eureka. The charcoal trade was a multifaceted industry and required a differentiated labor force that included: lumberjacks to cut timber, muleteers to transport the fallen timber, kiln or pit builders, timber packers. The kiln or pit controllers were the true charcoal makers, responsible for monitoring the varying temperatures inside the kiln or pit. Once the charcoal was produced it was bagged and loaded onto freight wagons and subsequently transported by the teamsters to the smelting furnaces in Eureka.

Obviously, not all charcoal makers were recruited by labor brokers on Italian soil. Some of them reached Nevada and the wilds of Eureka through the process known as “chain migration,” by which immigrants from a particular place follow others who have expatriated previously from the same location and have become established in the host community. Relying on such a support system, relatives, friends, or mere acquaintances (paesani) were enabled to emigrate with some assurance that a job would await them in the new land. Other Italians, already on American soil, reached Eureka after moving on from mining camps gone bust. Those who emigrated from Italy, after crossing the Atlantic, reached the Silver State by traveling across the American vastness aboard the transcontinental railroad. Completed in 1869, it joined the east of the United States on the Atlantic coast with the west to the Pacific coast. Another cluster of Italians trekked eastward to the Nevada frontier from California; among them there were some Forty-Niners who had raced to the Golden State following the discovery of gold. Although late nineteenth-century Nevada was a remote, industrial, and agricultural region large numbers of Italians settled in the Silver State, not just in Eureka, but in Reno, Virginia City, Ely, Paradise Valley, and Dayton as well.

We understand that life was not easy at all for the Italians in this area, right?

On the rugged frontier that engulfed Eureka, life was hard for all early settlers. But, by the mid-1870s of the XIX century, when the Italian population peaked, Eureka had grown into a prosperous mining center, affording its citizens comfortable living conditions. However, life for most Italian charcoal burners was extremely harsh; the very nature of their trade required them to live outdoors most of the year, in makeshift camps near the sources of timber, exposed to the elements of each changing season. Most lived in little burrows made of sticks and turf, unfit for human habitation. On those rare occasions, when the burners traveled to town for some well-deserved amusement, their leisure time was frequently spoiled by the townspeople's blatant hostility, often degenerating into brawls.

Not only did the burners contend with nature's rigors and with ethnic prejudice, they were also victims of an exploitative labor system perpetrated by the charcoal contractors, several of whom were Italian, by the teamsters who transported the charcoal, and by the smelters who processed the ores. Working in concert with one another these three entities conspired to exploit the burners. The contractors paid the burners starvation wages in the form of vouchers redeemable only at their supply stores; the teamsters weighted the charcoal at the smelting sites and did not disclose the contents of the receipts (weight and price) to the burners. The refusal by the smelters to deal directly with the charcoal producers at a lower cost convinced the burners that the whole trade was corrupt. Aiming at improving their deplorable working conditions and increasing their meager earnings, the burners formed the Charcoal Burners Protective Association (CBPA), hoping that by unionizing they would gain the necessary power to bargain with their antagonists.

One of the chapters of your book is called «The Charcoal Crisis». Is it true that at some point the tensions saw Italians on both sides, at war with each other?

Tensions within Eureka's Italian community surfaced as soon as the burners realized how exploitative their working conditions were. Most of their resentment was directed at their wealthy compatriots, the charcoal contractors who had engaged them back in Italy and now kept them in a state of servitude in collusion with other teamsters and smelters. The founding of the burners' union (CBPA) signaled the burners' determination to engage in political activity to improve their working conditions and it was viewed alarmingly by the burners' adversaries, several of them Italian.

Growing more daring each day, some of the more rebellious burners intensified their subversive raids particularly against those Italian charcoal ranchers, like Joseph Tognini, John Torre, and Peter Strozzi, who desisted from paying the higher price for charcoal demanded by the leadership of the CBPA. However, divisions within the recently established CBPA soon arose between the bolder burners who insisted on raising the charcoal price by any means, including violence, and those who refuted the any bellicose tactic and, although disheartened, were willing to resume charcoal production thus ending the stalemate.

Passions ran high among members of the two opposing factions, so much so that rows broke out in some of the local saloons, resulting in the death of a charcoal burner. After a month-long labor unrest and with no resolution in sight, local authorities and leaders of the business community, including two prominent Italians, Joseph Tognini and John Vanina, appealed to Nevada Governor Kinkead to mobilize the state militia and settle the charcoal crisis once and for all. The intra-etnic conflict that plagued Eureka's Italian community represents a historical instance of a clash between class and ethnicity. Ultimately, the economic interests of Eureka's Italian dominant class prevailed over ethnic bonds of solidarity with their impoverished compatriots.

Please tell us something about the event that was called “Fish Creek Massacre”

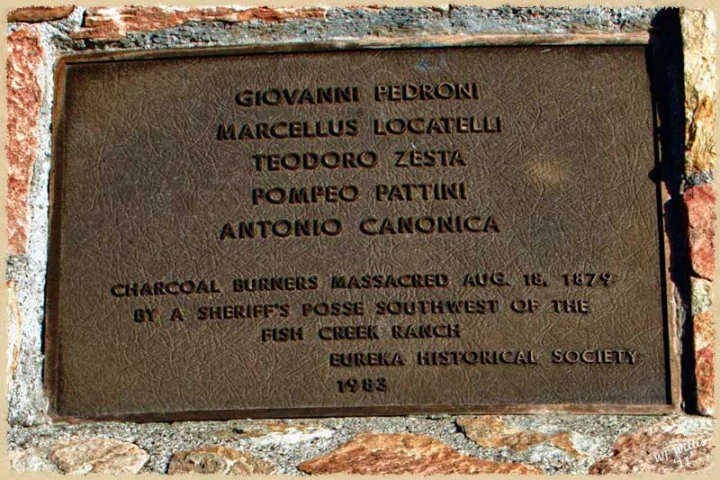

One of the largest and most turbulent charcoal camps of Eureka County was Fish Creek, thirty-miles from the town of Eureka. Although the state militia had been placed on alert, ready to intervene if the crisis deteriorated further, the local sheriff, the foremost lawman in Eureka, mortified by his repeated failures to subdue the riotous burners, attempted to redeem his tarnished reputation by making one last and desperate attempt to restore public order. On August 18, 1879, Sheriff Matthew Kyle dispatched an eight-men posse led by Deputy Sheriff J. B. Simpson to Fish Creek to serve arrest warrants of questionable legal validity. Sheriff Kyle's hoped that by arresting the ring leaders that had fomented the revolt their followers would capitulate. Deputy Simpson and his posse reached Fish Creek at dusk and were confronted by dozens of bellicose burners. Though greatly outnumbered and intimidated by the angry multitude, Deputy Simpson and his lawmen proceeded to serve the expedient warrants thus provoking the wrath of the defiant burners.

After an exchange of harsh words and threats on both sides, pandemonium erupted. Eyewitness accounts of the massacre at Fish Creek were contradictory. Posse members claimed the firing of a shot by one of the leaders of the burners ignited the shooting. Burners stated that the posse opened fire without provocation. Five burners died, six, at least, were wounded, and fourteen were arrested. Only one member of the posse was slightly injured. Close examination of the bodies of the slain burners revealed conspicuous traces of gunpowder in the chests of the victims, confirming that the burners had been shot at close range. Wielding the most lethal weaponry available at the time, the posse discharged its arms with remarkable accuracy as demonstrated by the mortal wounds sustained by the victims, all of whom were shot in the chest near the heart. The proximity and the precision of the shots fired by the posse led to the indisputable conclusion that the Fish Creek massacre was deliberately orchestrated and executed in cold blood by Eureka's law enforcers to protect the financial interests of Eureka's multi-ethnic business class.

A few months ago, the mayor of New Orleans officially apologized on behalf of her city for the 11 Italians killed in the shameful lynching happened in 1891. Is it something that has happened, or you think will ever happen, even for the Italians victims of the “Fish Creek Massacre”?

It would be extremely unlikely that an apology would ever be issued by Eureka's mayor, or by any other public officials, for the victims of the Fish Creek massacre. Having remained buried for more than 130 years there is hardly any public awareness about the tragedy, even among historians of the American West knowledge of the massacre is almost nonexistent. Although Nevada historian Shepperson compared the Fish Creek carnage to a Sacco and Vanzetti drama, and despite the considerable press coverage that followed the shooting, the remoteness of the crime scene and the lack of direct channels of communication caused public interest to be short-lived.

Unaware of the crucial details that led to the massacre, the incident was hastily dismissed by most as a mere case of foreign union rioters disturbing the social order by interfering with the lofty precepts of American capitalism. Further, the intra-ethnic nature of the conflict that led to the Fish Creek massacre, stands in sharp contrast with the 1891 New Orleans' lynching of the 11 Sicilian immigrants. In New Orleans a despised group of foreigners were scapegoated by American nativists intent on confounding the circumstances surrounding the murder of New Orleans Police Chief Hennessy. At Eureka, prominent Italian businessmen conspired with their American cohorts in the oppression of the charcoal burners and actively instigated the persecution of their compatriots, whose blood was ultimately and unjustly shed at Fish Creek.

La storia degli emigrati italiani che partirono per l'America è spesso una storia di difficoltà, di sofferenze, di incidenti. Spesso questi incidenti si verificarono in situazioni di lavoro vergognose e quasi impossibili, che erano le uniche rimaste per gli ultimi arrivati, gli italiani disposti a tutto pur di sopravvivere e permettere ai loro figli di avere un'educazione e una vita migliore. A volte ci furono delle prevaricazioni di natura discriminatoria.

Oggi incontriamo Silvo Manno, che ringraziamo: ha fatto ricerca e scritto un libro su quello che venne chiamato come "Fish Creek massacre" e accadde in Nevada. La cosa diversa da altre tragiche situazioni è che in questo caso i problemi nacquero tra due fazioni all'interno della stessa comunità, quella italiana. E' importante comprendere cosa accadde, per imparare dalle loro storie.

Silvio, sei l'autore del libro “Charcoal and Blood: Italian Immigrants in Eureka, Nevada, and the Fish Creek Massacre” (Carbone e sangue: Immigrati italiani a Eureka, Nevada, e il massacro di Fish Creek). Come ti è venuta in mente l'idea di questo libro?

Nel 1984 mi sono iscritto alla California State University a Fresno. Come studente universitario ho passato molto tempo nella biblioteca del campus. Dato il mio appassionato interesse per la storia dell'immigrazione, sono stato attratto dalla sezione di studi etnici e culturali della biblioteca. Lì mi sono imbattuto in un libro intitolato “Restless Strangers: Nevada's Immigrants and Their Interpreters” (Stranieri irrequieti: Gli immigrati del Nevada e i loro interpreti), scritto da Wilbur S. Shepperson, professore di storia all'Università di Reno, Nevada. Incuriosito dal titolo, ho scansionato l'indice del libro come facevo abitualmente. Con mio grande stupore, mi sono imbattuto in una voce dal nome: "Guerre italiane". Mentre indagavo più a fondo, venni a conoscenza del massacro di Fish Creek, un raccapricciante incidente avvenuto nell'estate del 1879 vicino a Eureka, Nevada, a seguito di uno scontro tra la banda di uno sceriffo di 9 uomini molto armati e decine di indigenti lavoratori italiani nelle miniere. La resa dei conti portò alla morte di cinque immigrati italiani, con numerosi feriti e molti arrestati. Colpito dal silenzio storico che aveva nascosto la tragedia per più di un secolo, silenzio già lamentato dal professor Shepperson, che paragonava il massacro a "un dramma di Sacco e Vanzetti", mi ripromisi di far luce sull'atroce delitto omesso dalla storia americana. Fu allora che nacque il sentimento per il libro per la prima volta. Tuttavia, sono poi passati molti anni prima che l'idea diventasse realtà.

Ci piacerebbe sapere di più sull'emigrazione italiana in Nevada. Da dove venivano quegli immigrati italiani, chi erano e come arrivarono in Nevada?

Venivano quasi esclusivamente dalle regioni del nord Italia: Lombardia, Piemonte e Liguria. La corsa all'oro in California del 1849 attirò moltitudini di immigrati da tutto il mondo, e un numero considerevole di italiani fu attratto anche dai giacimenti auriferi in cerca di fortuna. Ma, invece di cercare il metallo prezioso, la maggior parte di loro si dedicò al merchandising, per soddisfare le esigenze dei "Fourtyniners” (così venivano chiamati coloro che nel 1949 si riversarono in California alla ricerca dell’oro). Nel 1859 l'oro di superficie della California si esaurì e il business fu sostituito da miniere industriali finanziate da ricchi investitori.

Nello stesso anno, un altro grande sciopero scosse la frontiera mineraria, questa volta nel vicino stato del Nevada, dove era stato scoperto il deposito d'argento più ricco del mondo, il Comstock Lode. La notizia della scoperta si diffuse in lungo e in largo e folle di cercatori di fortuna si precipitarono nel Silver State (il Nevada). Dopo aver fatto molti soldi durante la corsa all'oro in California, provvedendo alle necessità dei minatori, diversi mercanti italiani si affrettarono a lanciare nuove iniziative commerciali sul Comstock. Decine di città spuntarono alla velocità della luce in tutta la regione. Preminente tra loro era Virginia City, centro in cui la presenza italiana era attestata dal prestigioso Molinelli’s Hotel, costruito negli anni settanta del XIX secolo. Man mano che la ricchezza mineraria del Comstock Lode si riduceva, nuovi scioperi venivano prospettati sia dai minatori che dagli investitori. Nei primi anni settanta del XIX secolo il piccolo campo minerario di Eureka, nel Nevada meridionale, rivelò i più grandi giacimenti di piombo amalgamati con l'argento negli Stati Uniti e forse nel mondo. Anche se abbondante, il minerale di Eureka si rivelò impegnativo e costoso da fondere. I due minerali potevano essere separati solo a temperature estremamente elevate, richiedendo grandi quantità di carbone per alimentare i forni di fusione. All'inizio degli anni settanta del XIX secolo il commercio del carbone veniva praticato esclusivamente dai cinesi, ma poiché l'intolleranza e la persecuzione contro di loro raggiunsero livelli inaccettabili, gli asiatici furono costretti a cedere il commercio agli italiani.

I nuovi arrivati provenivano prevalentemente dalle regioni alpine italiane, con un numero minore di persone provenienti dal cantone svizzero di lingua italiana, il Ticino, dove la produzione di carbone di legna era una pratica secolare. Reclutati da connazionali che fungevano da intermediari per conto di aziende americane e da imprenditori italiani in cerca di manodopera a basso costo, i potenziali immigrati venivano spesso ingannati da racconti troppo brillanti di facili ricchezze che si trovano alla frontiera mineraria del Nevada. In realtà, i lavoratori disperati e poveri, partiti verso la natura selvaggia americana, avevano inconsapevolmente accettato di entrare in un rapporto padroni/schiavi. Firmando il contratto, i mercenari italiani sostenevano pesanti oneri finanziari: il rimborso della traversata oceanica più gli interessi, il pagamento di vitto e alloggio fornito dai nuovi datori di lavoro, i salari pagati in buoni erano riscattabili solo nei negozi delle imprese appaltatrici, dove gli attrezzi e le forniture erano davvero troppo costosi. Inoltre, la loro incapacità di parlare inglese e la loro scarsa dimestichezza con le dinamiche della cultura americana ostacolavano notevolmente il loro adattamento. Tutti questi fattori esacerbavano la loro dipendenza dai “padroni”, rendendoli ancora più vulnerabili allo sfruttamento.

Sebbene gli italiani di Eureka fossero un gruppo eterogeneo di immigrati, tutti condividevano un background rurale e le capacità lavorative. Sfollati da un sistema agricolo semi-feudale arretrato, dall'instabilità politica, dall'aumento della tassazione e da una serie di fallimenti dei raccolti causati da siccità e inondazioni, un gruppo eterogeneo di contadini disperati ascoltò la promessa di un'occupazione remunerativa nel campo minerario del lontano Nevada. Anche se non tutti erano esperti di miniere di carbone, la maggior parte di loro furono impiegati nella produzione di una risorsa così preziosa sulle colline fuori Eureka. Il commercio del carbone era un'industria complessa e richiedeva una forza lavoro differenziata che comprendeva taglialegna per lavorare il legno, mulattieri per trasportare il legname, costruttori di fornaci o di fossati, imballatori di legname. I veri “carbonai” erano i responsabili del monitoraggio delle variazioni di temperatura all'interno del forno o della fossa. Una volta prodotto, il carbone veniva insaccato e caricato sui carri merci e successivamente trasportato dai camionisti ai forni fusori di Eureka.

Ovviamente, non tutti i carbonai venivano reclutati da intermediari del lavoro sul suolo italiano. Alcuni di loro avevano raggiunto il Nevada e la natura selvaggia di Eureka attraverso il processo noto come "migrazione a catena", per mezzo del quale gli immigrati provenienti da un determinato luogo seguivano altri che in precedenza erano espatriati dalla stessa località e si erano stabiliti nella comunità ospitante. Affidandosi a tale sistema di sostegno, i parenti, gli amici o semplici conoscenti (paesani) potevano emigrare con la certezza che un lavoro li avrebbe aspettati nella nuova terra. Altri italiani, già sul suolo americano, raggiunsero Eureka dopo essere passati dai campi minerari andati in rovina. Chi emigrò dall'Italia, dopo aver attraversato l'Atlantico, raggiunse il Silver State attraversando la vastità americana a bordo della ferrovia transcontinentale: completata nel 1869, unì l'est degli Stati Uniti sulla costa atlantica con l'ovest sulla costa del Pacifico. Un altro gruppo di italiani si incamminò dalla California in direzione orientale verso la frontiera del Nevada; tra questi c'erano alcuni “Fourtyniners” che erano giunti in California durante la corsa all’oro. Sebbene il Nevada di fine Ottocento fosse una regione remota, industriale e agricola, un gran numero di italiani si stabilì lì, non solo a Eureka, ma anche a Reno, Virginia City, Ely, Paradise Valley e Dayton.

La vita non era affatto facile per gli italiani in questo settore, giusto?

Sulla aspra frontiera che comprendeva Eureka, la vita era difficile per tutti i primi coloni. Ma, verso la metà degli anni '70 del XIX secolo, quando la popolazione italiana raggiunse il suo apice, Eureka si era trasformata in un prospero centro minerario, offrendo ai suoi cittadini condizioni di vita confortevoli. Tuttavia, la vita della maggior parte dei carbonai italiani era estremamente dura; la natura stessa del loro mestiere richiedeva loro di vivere all'aperto per la maggior parte dell'anno, in campi di fortuna vicino alle fonti di legname, esposti agli elementi atmosferici di ogni stagione che cambiava. La maggior parte viveva in piccole tane fatte di bastoni e manto erboso, non adatte all'abitazione umana. Nelle rare occasioni in cui si recavano in città per qualche meritato divertimento, il loro tempo libero era spesso rovinato dalla palese ostilità dei cittadini, spesso degenerando in risse.

I lavoratori non solo si scontravano con i rigori della natura e con i pregiudizi etnici, ma erano anche vittime di un sistema di sfruttamento del lavoro perpetrato dai carbonai, molti dei quali italiani, dai camionisti che trasportavano il carbone e dalle fonderie che lavoravano i minerali. Lavorando di concerto tra loro queste tre entità cospiravano per sfruttare i lavoratori. Gli appaltatori pagavano ai lavoratori un salario da fame sotto forma di buoni riscattabili solo nei loro magazzini di approvvigionamento; i camionisti pesavano il carbone di legna nei siti di fusione e non rivelavano ai lavoratori il contenuto degli scontrini, ovvero il peso e il prezzo. Il rifiuto delle fonderie di trattare direttamente con i produttori di carbone ad un costo inferiore convinse i lavoratori che l'intero settore era corrotto. Con l'obiettivo di migliorare le loro deplorevoli condizioni di lavoro e di aumentare i loro scarsi guadagni, i lavoratori formarono la Charcoal Burners Protective Association (CBPA), sperando di ottenere il potere necessario per trattare con i loro antagonisti.

Uno dei capitoli del tuo libro si chiama “La crisi del carbone”. È vero che a un certo punto le tensioni videro gli italiani avversari su entrambe le parti, in guerra tra loro?

Le tensioni all'interno della comunità italiana di Eureka esplosero non appena i lavoratori si resero conto di quanto fossero sfruttate le loro condizioni di lavoro. La maggior parte del loro risentimento era diretto ai loro ricchi compatrioti, i carbonai che li avevano ingaggiati in Italia e che ora li tenevano in stato di schiavitù in collusione con i camionisti e le fonderie. La fondazione del sindacato CBPA segnalava la determinazione dei lavoratori ad impegnarsi in attività politiche per migliorare le loro condizioni di lavoro ed era vista in modo allarmante dalle loro controparti, molti dei quali italiani.

Osando ogni giorno di più, alcuni dei lavoratori più ribelli intensificarono le loro incursioni sovversive soprattutto contro quei carbonai italiani, come Joseph Tognini, John Torre e Peter Strozzi, che non volevano pagare il prezzo più alto per il carbone richiesto dalla dirigenza del CBPA. Tuttavia, le divisioni all'interno del CBPA sorsero ben presto tra i lavoratori più audaci che insistevano per aumentare il prezzo del carbone con qualsiasi mezzo, nessuno escluso, e quelli che rifiutavano la violenza e, sebbene scoraggiati, erano disposti a riprendere la produzione di carbone ponendo così fine allo stallo.

Le frizioni aumentarono tra i membri delle due fazioni contrapposte, tanto che in alcuni saloon locali si scatenarono dei diverbi che portarono alla morte di un carbonaio. Dopo un mese di agitazioni sindacali e senza alcuna risoluzione in vista, le autorità locali e i leader della comunità imprenditoriale, tra cui due importanti italiani, Joseph Tognini e John Vanina, fecero appello al governatore del Nevada Kinkead per mobilitare le milizie statali e risolvere una volta per tutte la crisi del carbone. Il conflitto intra-etnico che colpì la comunità italiana di Eureka rappresenta un caso storico di scontro tra classe ed etnia. In definitiva, gli interessi economici della classe dominante italiana di Eureka prevalsero sui legami etnici di solidarietà con i loro compatrioti più poveri.

Raccontaci dell'evento che venne chiamato "Fish Creek Massacre"

Una delle più grandi e turbolente miniere di carbone della contea di Eureka era Fish Creek, a trenta miglia dalla città di Eureka. Sebbene le milizie statali fossero state messe in allerta, pronte ad intervenire in caso di ulteriore precipitazione della crisi, lo sceriffo locale, il principale uomo di legge di Eureka, mortificato dai suoi ripetuti fallimenti per sottomettere i lavoratori, tentò di riscattare la sua reputazione facendo un ultimo e disperato tentativo di ristabilire l'ordine pubblico. Il 18 agosto 1879, lo sceriffo Matthew Kyle inviò una banda di otto uomini guidata dal vice sceriffo J. B. Simpson a Fish Creek per eseguire mandati di arresto di dubbia validità legale. Lo sceriffo Kyle sperava che arrestando i capi del gruppo che aveva fomentato la rivolta, gli altri avrebbero capitolato. Il vice Simpson e la sua banda raggiunsero Fish Creek al tramonto e si trovarono di fronte a decine di lavoratori bellicosi. Anche se molto più numerosi e intimiditi dalla moltitudine arrabbiata, il vice Simpson e i suoi uomini di legge continuarono ad eseguire i mandati di cattura, provocando così l'ira dei lavoratori.

Dopo uno scambio di parole dure e minacciose da entrambe le parti, scoppiò un pandemonio. I resoconti di testimoni oculari del massacro di Fish Creek sono contraddittori. Alcuni membri del gruppo del vice sceriffo affermarono che tutto iniziò con uno sparo da parte di uno dei leader dei lavoratori. I lavoratori invece dissero che era stata la banda del vice sceriffo ad aprire il fuoco senza provocazioni. Cinque lavoratori morirono, sei rimasero feriti e quattordici furono arrestati. Solo un membro della banda del vice sceriffo rimase leggermente ferito. Un attento esame dei corpi dei lavoratori uccisi rivelò in seguito cospicue tracce di polvere da sparo nei corpi delle vittime, confermando che ai lavoratori era stato sparato da distanza ravvicinata. Munita delle armi più letali disponibili all'epoca, la banda del vice sceriffo colpì con notevole precisione, come dimostravano le ferite mortali subite dalle vittime, tutte colpite al petto, vicino al cuore. La vicinanza e la precisione dei colpi sparati dalla banda portò alla conclusione incontestabile che il massacro di Fish Creek era stato deliberatamente orchestrato ed eseguito a sangue freddo dalle forze dell'ordine di Eureka per proteggere gli interessi finanziari della classe imprenditoriale multietnica della città.

Qualche mese fa, il sindaco di New Orleans si è scusato ufficialmente a nome della sua città per gli 11 italiani uccisi nel vergognoso linciaggio del 1891. E' successo qualcosa di simile, o pensi che succederà mai, anche per gli italiani vittime del "Fish Creek Massacre"?

Sarebbe estremamente improbabile che il sindaco di Eureka, o qualsiasi altro funzionario pubblico, si scusasse per le vittime del massacro di Fish Creek. Essendo questo evento rimasto sconosciuto per più di 130 anni, non c'è quasi nessuna consapevolezza pubblica sulla tragedia: anche tra gli storici che si occupano della storia della parte occidentale degli Stati Uniti, la conoscenza del massacro è quasi inesistente. Sebbene lo storico del Nevada Shepperson abbia paragonato la carneficina di Fish Creek al dramma di Sacco e Vanzetti, e nonostante la notevole copertura della stampa che seguì alla sparatoria, la lontananza della scena del crimine e la mancanza di canali diretti di comunicazione fece sì che l'interesse del pubblico fosse di breve durata.

Ignorando i dettagli cruciali che hanno portato al massacro, l'incidente fu frettolosamente liquidato dai più come un mero caso di sindacalisti stranieri che disturbavano l'ordine sociale interferendo con gli alti precetti del capitalismo americano. Inoltre, la natura intraetnica del conflitto che portò al massacro di Fish Creek è in netto contrasto con il linciaggio di New Orleans del 1891 degli 11 immigrati siciliani. A New Orleans un gruppo di stranieri disprezzati dai locali fu capro espiatorio di americani intenti a confondere le circostanze che circondarono l'assassinio del capo della polizia di New Orleans Hennessy. A Eureka, importanti uomini d'affari italiani cospirarono con i loro compici americani nell'oppressione messa in atto e istigarono attivamente la persecuzione dei loro compatrioti, il cui sangue fu ingiustamente versato a Fish Creek.